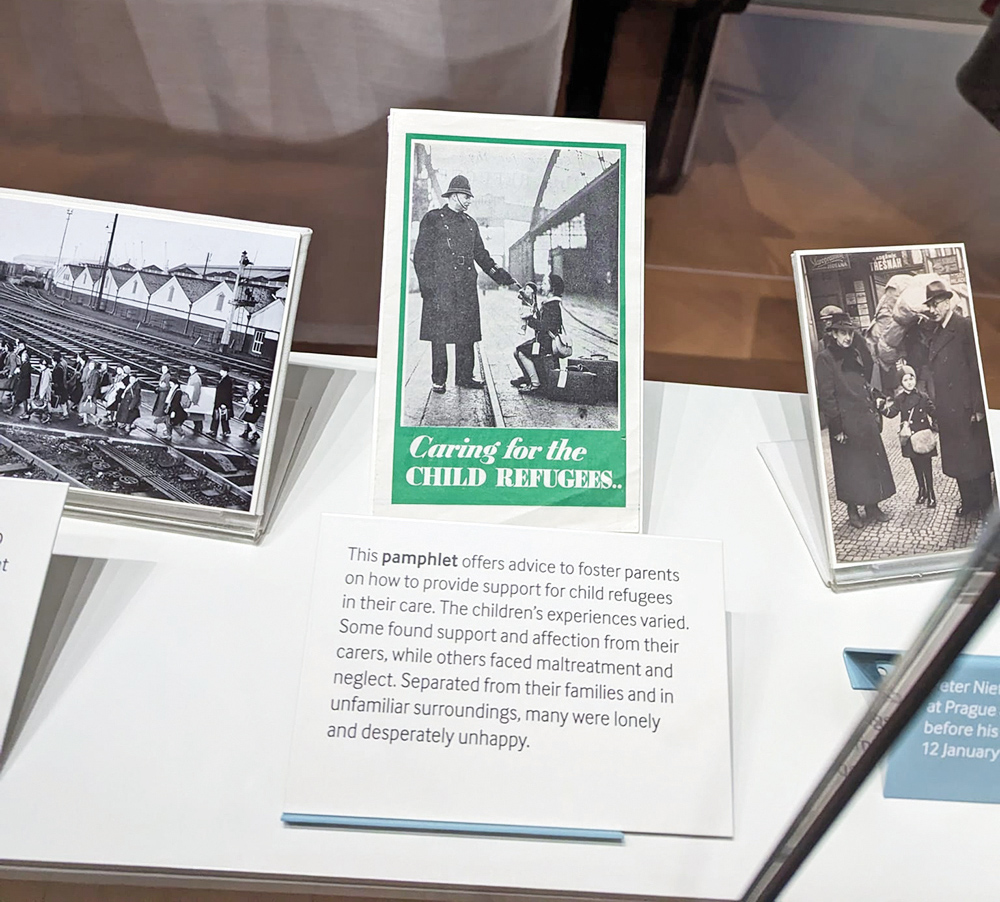

Nearly 85 years have passed since the first Kindertransport from Nazi-occupied Europe. Despite abundant documentation that England accepted approximately 10,000 Jewish children, the stories of refugees’ travails and how their lives evolved are not nearly as well known. Kindertransport children contributed greatly to their adopted homeland and to society at large, despite traumatic separation from their families, varied placements as fostered or adopted children, evacuation to the countryside during the “Blitz,” and subsequent challenges.

(Credit: Jewish News, UK)

Considering the odds against them, the extent to which those children lived full, successful lives is staggering. Artists, industrialists, businessmen, jurists, statesmen and others have served the United Kingdom and world well. This is not to imply that all refugee children’s experiences were positive; certainly, some were mistreated and exploited. Nevertheless, that individuals and families in a country under siege absorbed significant numbers of displaced strangers, and did so, overall, with kindness, is remarkable.

Unraveling Shared Histories with Ongoing Impact

The number of Kindertransport survivors is rapidly dwindling, which makes it crucial to keep their stories alive. I recently researched their Kindertransport experiences, how they coped in wartime, and how they managed to rebuild their lives afterwards. This involved a screening at the British Film Institute (BFI), visits to the Holocaust Galleries, Imperial War Museum (IWM), London (https://www.iwm.org.uk/events/the-holocaust-galleries), the Generations exhibit (https://www.iwm.org.uk/events/generations-portraits-of-holocaust-survivors), recorded testimonies, additional Kindertransport artifacts and photos at IWM North (https://www.iwm.org.uk/search/global?query=kindertransport), and direct interviews with Kindertransport survivors and their children.

In Sue Read’s (2000) film The Children Who Cheated the Nazis, many Kindertransport children recount their moving experiences. Narrated by the late actor/director Lord Richard Attenborough (whose family fostered, then adopted orphans Helga and Irene Bejach), the film cuts between survivor accounts and re-enactments of the children’s journeys. They reveal the trauma of leaving loved ones and children’s fears as they escape and face uncertain futures.

A Community Member, Seen in a New Light

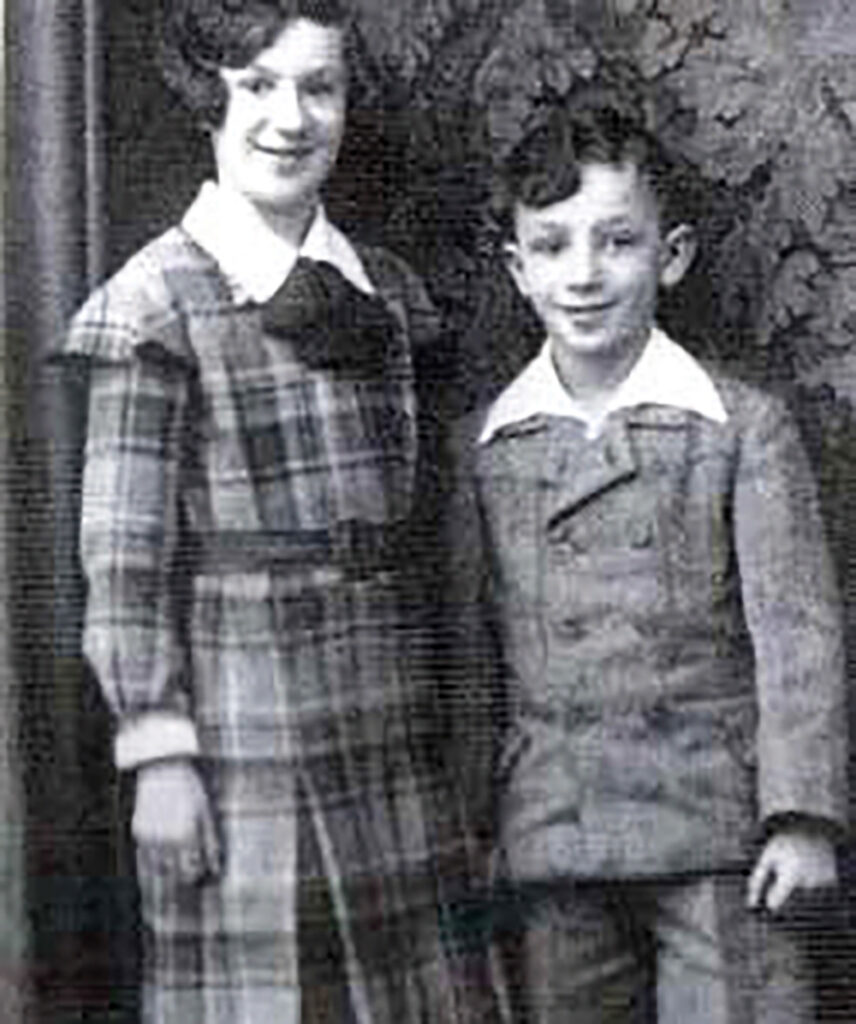

I watched the screen in shock, unaware that Emmy (Hubert) Mogilensky, whom I knew from Baltimore, had been on a Munich-bound Kindertransport in 1938, and then a boat for England. Her emotions surged as her father blessed her and she saw him, frozen with sadness, as the train departed. Despite her own grief, she tried to comfort a catatonic boy. The train slowed briefly, a door opened, and someone pushed a wicker basket onto the train. As the eldest child present, others expected her to open it, which she did.

(Credit: The Steinberg Family)

Inside were two crying babies, under which were two bottles and two diapers each. She picked up and fed one baby; a boy fed the other. The boys all donated their handkerchiefs, which the girls tied together to create additional diapers. The children cleaned the diapers with water and spread them over the seats to dry.

Terror at Nazi Inspections

Kindertransport survivors described their terror near the border with Holland. Mogilensky remembers a Nazi soldier boarding the train. He checked that the number of suitcases matched the number of children. He demanded to know the wicker basket’s owner. Mogilevsky claimed it, and the soldier shouted at her about the extra baggage. He then removed his rifle and probed the wicker basket with its bayonet. The babies awoke and began to cry. The soldier looked inside and was silent. Would he return them to Germany, to an unknown fate, or let them continue the journey? The babies remained on the train.

Mogilensky resolved not to let them leave her sight until they were all safely in England. “If England can take a whole train full of children,” she said, “they can take two babies as well.” Although the fate of those babies’ relatives was unknown, in 1980, one of the babies invited Mogilensky to her son’s bar mitzvah. It was “wonderful.”

In June 1939, Selmar Hubert joined his sister, who had found an English family to take him. After the war, she married a Jewish-American soldier whom she met during the High Holy Days. They moved to Albany, New York, raised a family, and she switched careers from teaching to technology. Later, she joined her children in Baltimore, shared her story often, and worked and volunteered with non-profits.

Kindness That Superseded the Cruelty

The arbitrary, unpredictable inspections by German soldiers of children and suitcases, such as Mogilensky described, were not isolated incidents. Susanne Medas, whose oral history is recorded at the IWM North, recalls how children were forced by the Germans to open their suitcases to check for contraband.

Medas conveys the children’s happier mood once the train reached Venlo, Holland. Like Mogilensky, she reminisces how in this small farming town, Dutch women, alerted to the train’s arrival, came with baskets full of bananas, oranges, and cocoa for the children on board. In addition to the food they brought, their abundant hugs helped to comfort traumatized children.

Leni Steinberg—Life in England After the Terror

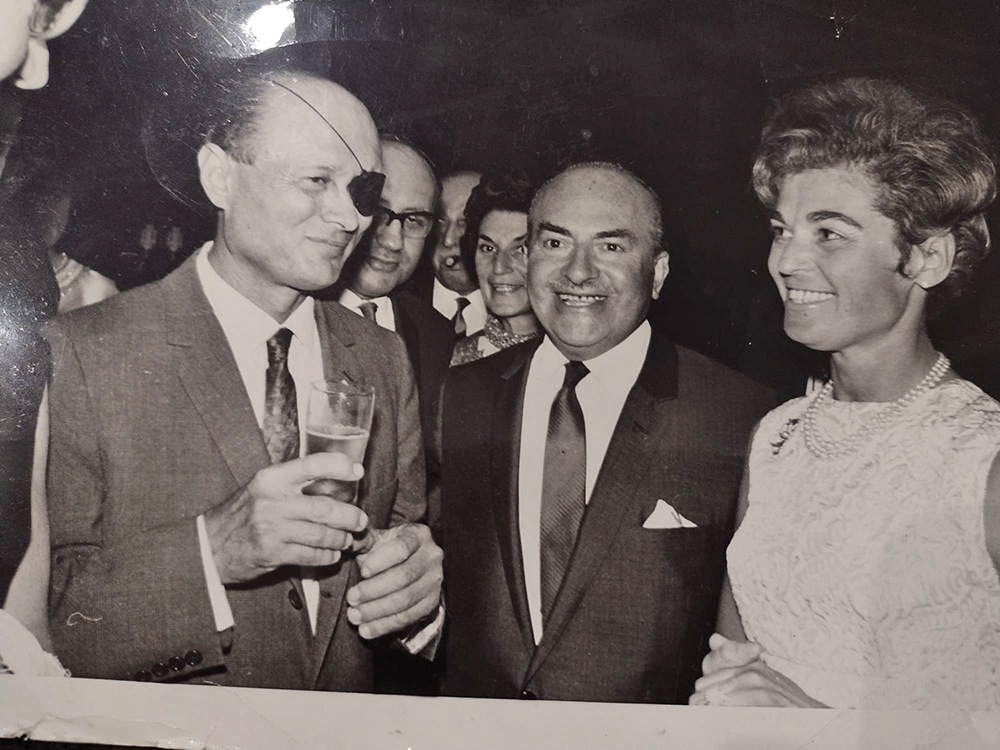

I interviewed Hammerson House, London resident Mrs. Leni Steinberg, one of six children born in a small Czech town. Her religious father moved his family close to Prague’s main synagogue after the Nazis occupied Sudetenland in 1938. She remembers little of that time, other than her non-Jewish school. Her father’s cousin in England warned him to emigrate, as male relatives had already been sent to concentration camps.

Mrs. Steinberg, her brother Jack, and baby Esther traveled on a Kindertransport. She recalls, “Going to the train was a very traumatic, most terrible… a very frightening experience. Women were crying, children were crying, …the Gestapo came in to look at the children. I found that terrible…Men with big guns, the children were quite terrified (but) they never came near us, never touched the children…I still remember so vividly…those awful men coming on the train.” She only remembers one stop, at night, on the coast, where they boarded the boat to England, arriving just before WWII started. In England, her father had arranged places for them. “If it wouldn’t have been for my father, we wouldn’t have been able to come.” With neither money nor language skills, he struggled, but the Jewish community helped him. “…It was much harder for my father…He did his best.”

Mrs. Steinberg helped an elderly London Jewish resident, Jack went to a farm, and Esther was fostered. During the Blitz, Mrs. Steinberg was evacuated to Peterborough; the non-Jewish family gave her a horse to ride. School was infrequent. Everyone was very nice, but overall, Mrs. Steinberg says, the whole thing was terribly traumatic…” without her parents, and totally alone.” Meanwhile, her mother and the remaining three siblings made their way through Hungary and eventually reached England. Esther’s foster mother only reluctantly relinquished her.

Mrs. Steinberg, who married a Jewish doctor, and most of her siblings settled in England.

Although the Rosners’ story also ended well, at times that outcome was less than a given.

From Kindertransport to Einstein Medical College and Expertise in Jewish Medical Ethics.

Berlin, November 1938. On Kristallnacht, the Rosner family had witnessed Sifrei Torah burning. A few days later, Mrs. Rosner decided to send her children, Dr. Fred Rosner, 3, brother Eli, 11, and sister Pearl, 8, by train to Holland. The boys were permitted to continue to England, but Pearl was removed from the Kindertransport and hidden with a Christian family who moved to Belgium; ultimately, Pearl was returned to her parents and hid with them in Brussels.

The Rosner brothers went to a transit camp near Ipswich, where a Miss Heimler cared for the younger boy. In 1940, England’s South was bombed. The brothers were evacuated to orphanages in Ilkley, and nearby Leeds. The Ilkley orphanage was a secular Jewish institution, but Miss Falk, the younger boys’ supervisor, lit Shabbos candles. Eli, in Leeds, was able to keep kosher, frequently visited his brother, and equipped with some Jewish education, served as his “spiritual conscience.” Eli made boots for the soldiers. Their Uncle Shlomo, who had moved to London before them, would visit every few months to check on their wellbeing. Until 1942, Eli corresponded with his parents via the International Red Cross; after that he did not discuss his parents’ and sister’s fates.

Every Sunday, the orphanage’s children, dressed in their best, were displayed before prospective adoptive parents, Jews, and non-Jews. A watchful brother, Eli always interfered when visitors showed interest in his blond-haired brother and would not let them adopt him. Dr. Rosner lived in the orphanage until age 11, excelled academically, and skipped several grades. In English high school (1945-46), he was excused from Anglican prayers.

The rest of the Rosners had hidden throughout Brussels and were liberated in 1944. They were reunited in 1946 in a providential (read miraculous) way, particularly as they didn’t know each other’s whereabouts. A religious British soldier who came to Brussels was referred to the Rosners for Shabbat. During a meal, he mentioned that where he prayed in London, there was a Mr. Rosner who, every few months, visited his nephews up north.

The International Red Cross located Eli and Dr. Rosner. In April 1946, Eli immediately joined his family in Brussels, but Dr. Rosner relished his studies so much that he remained in England to finish the school year. In September 1946, Miss Falk escorted him to London, where a member of the Jewish Refugee Board brought him to Dover and then to Ostend, Belgium. The Red Cross handed him over to his father, whom he did not recognize. On the three-hour Ostend-Brussels train, their language barriers precluded communication.

Dr. Rosner learned French (for school and to communicate with Pearl), German, and Yiddish (his parents’ languages). In 1948, he celebrated his bar mitzvah in Brussels, where the Rosners remained until June 1949, when they emigrated to New York. HIAS placed them in Washington Heights, where Dr. Rosner studied at Yeshiva University, and at Albert Einstein Medical College, as part of Einstein’s first graduating class. Dr. Fred Rosner became an internationally renowned hematologist and authority on Jewish medical ethics.

Each Kindertransport story is priceless, and every journey taken, every challenge faced is a chapter in a larger history of upheaval that is a prequel to rebirth. As Tisha B’Av approaches, we need to remember the lessons of the past, and increase our resolve to build a more harmonious and lasting future.

Rachel Kovacs is an Adjunct Associate Professor of communication at CUNY, a PR professional, theater reviewer for offoffonline.com—and a Judaics teacher. She trained in performance at Brandeis and Manchester Universities, Sharon Playhouse, and the American Academy of Dramatic Arts. She can be reached at mediahappenings@gmail.com