When I read about the arrest of American Jewish Wall Street Journal Reporter, Evan Gershkovich, in Russia on March 29, my mind went back to the 1980s.

In July 1985, I went to visit Abe Stolar. Abe was well into his 70s. We bonded immediately, two American Jews, me listening to his stories intently, in his native Chicago accent. The strange thing is that I was not visiting Abe and his wife, Gita, in Chicago, the place of his birth, or in New Jersey, the place of my birth. I was visiting Abe in Moscow, the Soviet Union.

Like many Russian Jews, Abe’s parents fled Czarist Russia. They arrived in Chicago, a year before Abe was born. In 1931, with the US still suffering from the Depression, exacerbating a degree of communist revolutionary fervor, Abe’s parents decided to go back to the USSR. Within five years, Abe’s father was taken from their home by Stalin’s police (NKVD) during the infamous purges in which many Jews became victims. Abe’s father was never seen again. Despite being an American citizen, Abe saw no way back to Chicago. So much for the Beatles’ 1968 sympathetic portrayal of the USSR.

In 1975, Abe, Gita and their son applied for exit visas. They received permission to leave, selling all their belongings. On July 19, their permission was revoked. The Stolars were detained just before boarding the plane, forced to return to their empty Moscow apartment, hopeless.

I met Abe a decade later, almost to the day. He was clearly frustrated and desperate to leave, but he was jovial, friendly, and welcoming. Two years later, I went back to Moscow and visited Abe again. He was more hopeful as he saw signs that things in the USSR were changing, but he was still an American citizen forcefully detained in Moscow.

As soon as I heard of Evan Gershkovich’s arrest, I thought of Abe. Evan was arrested on charges of espionage by Russia’s Federal Security Bureau (FSB), the successor to the KGB, and Stalin’s NKVD. It’s the first time Russia has accused a foreign journalist of espionage since the Cold War.

There are many parallels between Abe Stolar and Evan Gershkovich. Both are American Jews, both detained in Russia, both children of Russian-born Jews who emigrated to the US, and both went back to Russia as young men, albeit Evan went of his own accord in a professional capacity. He probably didn’t know about Abe Stolar, and that there was a precedent for Russia detaining American-born Jews.

Shortly after Evan’s arrest, Jews around the world were asked to set an extra seat for him symbolically at their Passover Seder table. It’s interesting that leaving seats empty at the Seder table was something done in the height of the movement to free Jews of the Soviet Union, the time when Abe Stolar first tried to leave and, when Gershkovich’s parents actually left the USSR.

Setting empty seats at a Seder table is meaningful because Passover is the holiday during which we celebrate our freedom. Jews being detained, arrested, imprisoned as Jews (on trumped up charges) is evocative of the enslavement of Jews in Egypt. This creates awareness, and is meaningful especially when the person for whom that seat is set is a Jew being forcefully detained. It builds solidarity, but is unlikely to do anything on its own to effect a change in Russian policies, or free someone who has been arrested.

It’s clear that Russia is using Evan to retaliate or as leverage against the U.S, or both. Evan’s arrest will intimidate other western journalists still reporting in Russia, making a black hole of already limited information coming out of Russia even deeper and darker. Perhaps Evan was not targeted as a Jew, but it’s now no longer unusual for Jews in Russia to be in the Kremlin’s crosshairs.

Abe Stolar’s case became very personal to me. Especially after my adopted Soviet Jewish family was permitted to leave in 1987, I stepped up my activism on his behalf, one of many doing so. When I read about Evan Gershkovich, something additional and personal struck and engaged me. Albeit some years after I graduated, Evan also graduated from Princeton High School, in the suburban New Jersey community in which I grew up and where my Soviet Jewry activities began.

Not that I am a journalist as Evan is, but in my advocacy to free Jews from Russia, I began writing articles as one of my forms of advocacy, including in the Princeton High School student newspaper. People commented on my being a Jewish student at a particularly WASPy school, in a particularly wealthy community, writing about the imperative of freeing Jews from Russia. For most, it was the first exposure any of my fellow students knew about the antisemitic treachery of Soviet policies.

Today, the imperative to do so has come full circle. Espionage was one of the trumped-up charges the Soviets would use against Jews in the past. It seems that it’s a play in Russia’s play book as well under Putin, a former KGB agent.

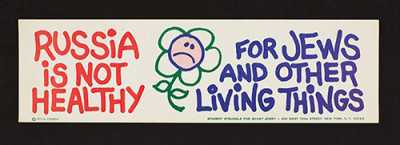

As much as things have changed in the past decades, it’s astounding to see how much things have stayed the same. The pin and bumper sticker I still have from my Soviet Jewry activism days, “Russia is Not Healthy for Jews and Other Living Things,” are more than just nostalgic collectors’ items, but still a sad truth.

For Abe Stolar, the fraud of Soviet communism became apparent shortly after his family moved back. In 1989, 58 years later, he and his wife and son were finally permitted to leave the USSR to Israel where he lived out the last years of his life. Hopefully, Evan will be freed shortly.

The Soviets then, and Russia today, need motivation to change. Optics matter. In the 1980s, I initiated protests at the Russian Embassy in Washington, participated in other massive protests, and called Soviet embassies all over the world to make my protest heard in their offices, to frustrate and embarrass them, and make it no longer worthwhile to use Jews or others as pawns.

The Russian Embassy can be reached at (202) 298-5700.

Jonathan Feldstein, formerly of Teaneck, made aliyah in 2004 and now lives in Efrat.