The 41 Jews aboard the “William and Sarah,” many of whom were of Portugese descent, departed from Great Britain and docked on the shores of Savannah, Georgia, in July of 1733 with the hopes of having successfully escaped the Spanish Inquisition and of being more warmly accepted in the New World. The passengers came armed with belongings and experiences that would later end up becoming artifacts and bits of history that their descendents, and fellow Jews, would treasure for years to come.

I recently returned from a vacation to Savannah where I had the pleasure of visiting Congregation Mickve Israel, the third oldest shul that had become home to the early Sephardic and Ashkenazi Jews of Savannah. During my tour, led by Rabbi Robert Haas, who has been serving as Mickve Israel’s rabbi for seven-and-a-half years, I learned all about the temple’s history and how its congregation still thrives today.

Luckily for that first boatload of Jews back in 1733, a doctor was included amongst its many passengers. The founder of the Georgia colony, James Edward Ogelthorpe, welcomed Dr. Samuel Nunez Ribeiro and his ability to help treat Georgians suffering from yellow fever, a disease the doctor already had experience treating. The relationship between Nunez and Ogelthorpe remained remarkably peaceful, which no doubt helped keep the Jews in good standing amongst the Georgians. The Jewish population was only destined to grow—the second boat of Jews to dock at Savannah’s shores happened just a few years after the first.

The sanctuary for Mickve Israel, which is now a Reform shul, was constructed in 1820, but was destroyed in a fire nine years later. (The Torah and the ark were saved.) Another one was built in its place in 1835. In 1878, a new building at a different site (Monterey Square) was completed to accommodate the wave of German-Jewish immigration that began a few years prior, and that was the building I visited on my tour.

If you’re looking at the shul from the outside, you might mistake it for a church because of its Gothic revival architecture, which was a common design for the time period. The inside is no less beautiful. It is also one of the very few shuls, Rabbi Haas believes, that functions both as a museum and a house of worship.

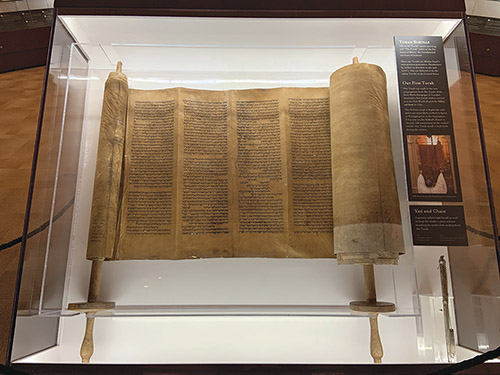

Of the many exhibits available, the most precious had to be the two Torot, kept safe behind glass. The first was brought along with the first group of Jewish settlers in 1733; the second was brought by the Ashkenazi Jews who arrived in Savannah in 1737 from the Bevis Marks Synagogue, which is the oldest shul in the United Kingdom still in continuous use. Both were scribed in Sephardic style on deerskin, likely in the mid-1400s.

The congregation used to read from the Torot every year during its anniversary service, until a few years ago, when they became much too fragile to remove from the glass.

“The Torah is not considered kosher anymore,” Rabbi Haas said. “All of the words aren’t legible, there’s a lot of water damage—they’re about 550 years old.”

The museum also kept the congregation’s first circumcision kit on display, which was brought along with the first settlers.

“When we were told we couldn’t use the Torah anymore, we stopped using the circumcision kit as well,” Rabbi Haas said. (He was kidding.)

Right next to the circumcision kit sat a brass menorah that Rabbi Haas explained was debated to have been used by Jews during the Spanish Inquisition. It was made in either Spain or Portugal during the 15th or 16th century, and could be folded to hide its true nature and its Hebrew lettering, which was likely necessary for Jews forced to practice in secret.

One of the most eye-catching relics had to be the stained glass windows that occupied the sanctuary, as well as the sanctuary itself. The set of three windows over the bimah, painted in vibrant blues, pinks and yellows, were original to the 1878 building. They were designed by Rabbi Isaac Mendes and built by William Gibson’s Sons of New York. They cost about $500 to install (in 1878, that amount of money went a long way). Many more larger windows along the walls let bright, colorful lights into the room.

While the artifacts were a strong testament to the city’s history, the people who helped build such an early Jewish community could not go unrecognized. While they did assimilate to American culture (many owned slaves), many men and women helped gain approval and respect for their fellow Jews amongst the Savannahians at the time.

In 1742, a battle broke out between Spain and Great Britain, which was part of a larger war (The War of Jenkins’ Ear) between the two countries that had begun in 1739. Spanish troops soon invaded Georgia, and the Sephardic Jews living in Georgia feared that Spain would capture and punish them (since they had illegally evaded persecution years earlier). They fled Savannah, leaving Ashkenazi Jews in their wake. Two Ashkenazi families that stayed were the Minis and Sheftall families, who held services in their homes before the shul itself was built.

Benjamin Sheftall founded the Union Society, the earliest known interfaith organization during the colonial period. His son Mordecai Sheftall, also an observant Jew, served as a colonel in the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War—he was the highest ranking Jewish officer of the colonial forces. He also became chairman of the Parochial Committee, which was organized in part to oppose British rule.

When the British attacked Savannah in 1778, Mordecai Sheftall defended his city, but he and his son, Sheftall Sheftall, were eventually taken prisoner and weren’t released until 1781, due in part to Mordecai’s wife (Frances Sheftall) and her letter campaigns to the British government.

Mordecai’s brother, Levi, was credited with starting the legacy of correspondence between Mickve Israel and sitting U.S. presidents when he first wrote to President George Washington to congratulate him on his position. President Washington sent a letter back wishing the Jewish community a successful legacy in the U.S., comparing its presence in the New World to the Jewish people (in Biblical times) finally seeking the promised land under Hashem’s protection.

Abigail Minis came along on the “William and Sarah” in 1733 with her husband, Abraham, and their two daughters. After her husband died in 1757, Minis became tasked with operating her husband’s ranch while raising their now eight children. While she struggled to speak English, and even sign her own name, she was a woman with a knack for business. She purchased land throughout Georgia and South Carolina, and soon outpaced her husband’s success. She also applied for a license to own and operate her Minis Tavern, which became the go-to spot for the city’s elite. She was a shining example of what success women were capable of during a time when they were largely taken for granted.

Many other remarkable people that helped shape Savannah’s Jewish history include Herman Myers, Savannah’s first Jewish mayor, elected in 1895, and then re-elected three times; Eugenia Philips, a Confederate spy during the Civil War; and Rabbi George Solomon, the first Reform rabbi of Mickve Israel.

Fast forward to the 20th century, when three of Mickve Israel’s congregants were among the first five Girl Scout leaders, the organization that was headed by Juliette Gordon Low in Savannah in 1912. The museum has a framed certificate signed by Low approving one of the member’s acceptance into the organization.

Mickve Israel continues to head other city-wide programs that help keep the Jewish community alive in the minds of Jews and non-Jews alike.

One such program is the Shalom Y’all Jewish Food Festival, which will celebrate its 33rd anniversary in the spring of 2021. The shul will have a smaller festival in October of this year. The fundraiser is held in Monterey Square, near the center of Savannah’s Historic District, and is one of the largest Jewish food festivals in the country. Savannahians come to enjoy homemade Jewish food (think corn beef, tongue and pastrami sandwiches, potato latkes, blintzes, challah, hummus and pita, kugel, matzah balls and much more) and celebrate Jewish culture.

“We get anywhere from 5,000 to 10,000 people,” Rabbi Haas said. “It’s incredible because there’s only around 140,000 people in the whole city.”

All I’ve covered are really just the highlights. To learn more about this corner of Jewish history, I recommend you give Savannah, and Mickve Israel, a visit. Happy travels.

By Elizabeth Zakaim

�