On January 28, a powerful event unfolded to commemorate International Holocaust Remembrance Day and the 80th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau. Jamie Dimon, the CEO and chairman of JPMorgan Chase, had extended a heartfelt invitation to Holocaust survivors and twin brothers Henry and Dr. Bernard Schanzer to share their deeply harrowing, inspiring story of survival.

The event began with Dimon delivering a somber reflection on the lessons of history. He drew parallels between current global conflicts and the atrocities of the past. He pointed to the invasion of Ukraine and the terrorist activities against Israel, and noted, “We said, ‘never again’ in World War I; we said ‘never again’ in World War II, particularly regarding the Holocaust, and it is, in fact, ‘again.’”

Henry Schanzer began by sharing his and Bernard’s family background. Their mother, Bella, was born in Poland, and their father, Bruno, was born in Slovakia. Their parents immigrated to Belgium in the late 1920s, where they met and later married. Their older sister, Anna, was born in 1934, and they were born in 1935. Their childhood in Belgium was abruptly disrupted when the Nazis invaded in May 1940.

Dr. Lindsay MacNeill, listening as Jamie Dimon introduces the event.

Bernard recounted the chaotic flight of their family: “Within a few days of the German invasion of Belgium, 13 members of our extended family crammed into a small van and we fled towards France.”

After two years of relative normalcy in France, everything changed again in the summer of 1942. Henry shared, “The roundup of 10,000 Jews in Paris sent shockwaves through the Jewish community.”

The twins were soon separated from their family. “Our parents sent Henry and me to a gentile acquaintance of our father’s who had agreed to board us,” Bernard said.

“Etched in my memory is that hot summer day when Papa carried our suitcases, and we held on to the suitcases and to our father, walking to the bus depot,” Bernard continued. “When we got there, we sat in our father’s lap. He hugged us and hugged us. He began shaking and sobbing. Our father had never shown much emotion in public. And here he was, visibly crying.” He and Henry were taken to their new guardians, whose names they don’t recall, so they have dubbed them “Madame and Monsieur Cretien.”

A few days later, to the boys’ delight, their mother came to visit them. When she returned to the family’s apartment, she found it had already been seized and locked. “On that day, August 26, 1942, she discovered that all of our family members who had remained in St. Etienne had been arrested, including our father, his brother Max, our uncle Boris Shapiro, and our 7-year-old cousin, Jack.” In a stroke of luck, Jack was released after his father signed a document abandoning him. This act rendered Jack a ward of the state, making it impossible for the French authorities to hand him over to the Germans. Tragically, apart from Jack, none of the other family members ever returned. Their father, Bruno, was transferred to a camp outside of Paris, and then sent to Auschwitz.

The boys’ initial welcome at the “Cretiens” soon soured as the couple stopped receiving funds from the Schanzers. Bernard said: “Days later, Monsieur ‘Cretien’ told us to pack our bags because we were going on a trip. We thought, with excitement, that we would be reunited with Mama and Papa and our family.” Instead, they were taken to a police station, and then to a Catholic orphanage.

Henry described their experience in the orphanage: “We had been there for two months when we experienced what we call ‘the great escape.’” He recounted how two men approached them as they were crossing the street, telling them to stand at the very back of the line the next day. “We didn’t question the message or the messenger. The next morning, we made sure to be at the back of the line. As we crossed the street, the two men appeared, took our hands, and calmly walked away with us.

“It turns out the two men had acted in response to our mothers’ request,” Henry continued. They were part of the OSE, a clandestine Jewish organization that helped Jewish children in Vichy, France. “To this day we don’t know how our mother had learned where we were and how our escape was so well engineered.”

The brothers were taken to a farm, where “we were malnourished and became very sick,” Bernard recalled. After several months, they were rescued again by a man from the OSE who saw their condition and brought them to another orphanage.

Meanwhile, their mother was in hiding. In the spring of 1943, Bella found herself wandering the streets of St. Etienne when, by chance, she encountered Madame Jeanne Bonhomme, the owner of a local dress shop, with whom she had developed a warm rapport over the past two years. Bonhomme immediately offered assistance, demonstrating remarkable bravery and selflessness by helping a Jew in distress. She secured a false identity card and birth certificate for Bella, as well as a safe haven in a historic castle owned by Xavier and Marie-Françoise de Virieu, a marquis and marquise involved in the French resistance. At Bella’s request, Bonhomme negotiated with the OSE to locate the boys. She retrieved them from the orphanage in the spring of 1943, placing them with her own mother, Madame Adolphine Dorel, in St. Pal de Mons. The boys quickly formed a strong bond with Madame Dorel, whom they called “Mémé” (Grandma).

Despite the constant threat of discovery, the twins found solace in their bond with Mémé, who treated them as her own. “When we were on the farm, there were times we went hungry. But if we were hungry, so was she. Whatever she had, she shared with us.” Bernard reflected.

Armed with a false birth certificate and identity card, Bella managed to find places to work and survived several close calls until the end of the war. Bernard and Henry continued to live with Mémé until August 1945 when they were finally reunited with their mother, whom they had not seen in over two years.

After the war ended, the Schanzer family immigrated to New York’s Lower East Side. Their father had not survived the war. “My cousin Jack, whose parents had been murdered, came to live with us,” said Bernard. “He had been physically and emotionally traumatized.”

Their mother was a 45-year-old widow who worked very hard to provide for them.

“Henry received an engineering degree and went to law school. I went to medical school,” Bernard recounted. Their sister Anna survived the war as well. She attended Hunter College and became a French teacher.

In 1980, Anna petitioned Yad Vashem to award Madame Bonhomme and posthumously Madame Dorel (Mémé) the medal of righteousness. “The medal quotes a

saying from the Talmud: ‘He who saves one life, saves the whole world,’” Henry said.

Madame Bonhomme, accompanied by her grand-niece, came to New York from France to attend an inspiring ceremony at the Israeli consulate. “It was a glorious moment for Madame Bonhomme to see the children and the worlds that she had saved,” Henry said.

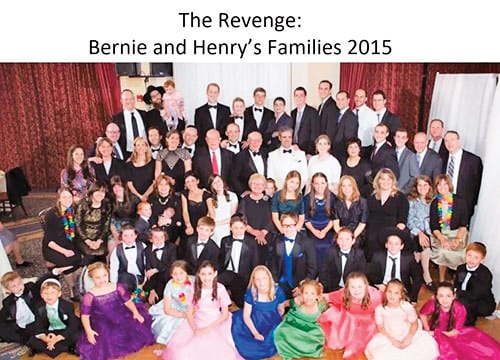

The men shared a photo of their large families, the descendants of Bruno and Bella Schanzer, on the screen. “We titled the photo ‘The Revenge’—to declare that the attempt by the Nazis to destroy the Jewish people had not succeeded,” said Bernard, and left the audience with a call to action: “We ordinary people must emulate Mémé, the marquise and marquis, and Madame Bonhomme. These noble individuals risked their lives, not once but continually, to save us. But for them, we would not be here. We told you our story, and now it is yours. This is our gift to you. Your presence here shows that you are not indifferent. Your presence here is your gift to us. We cherish it for it represents the gift of hope—the greatest gift.”

Henry added his concluding thought: “We must remember and honor the righteous saviors and all of the pure and innocent lives that were destroyed. In addition, in the words of President Lincoln, we must resolve that these honored dead shall not have died in vain. So we ask all people of goodwill to be proactive in fighting the evil we have endured so that ‘never again’ will in fact be ‘never again.’”