I never imagined that one day I would meet Elie Wiesel. The way that it happened was even more surreal than the fact that it happened. Last week, this deeply embedded, unique memory surfaced as I read about Mr. Wiesel’s seventh yahrzeit. He passed on the 26th of Sivan, which this year fell on Wednesday night and Thursday, June 14-15.

It was December 3, 2014. My son Mayer had purchased tickets for Itzhak Perlman’s first solo concert in years. We arrived early at Alice Tully Hall, Lincoln Center. I hoped to greet Mr. Perlman, whom I had previously met, and hand him my paper about the impact of his friend Christopher Nupen’s documentary, We Want the Light, on my students’ grasp of the Holocaust.

Mayer and I entered the stage door. Mr. Perlman’s wife Toby, who appeared near the security desk, suggested that we return after the concert. We did. My son sat near security, while I took the elevator upstairs and wove through the well-wishers to greet a very gracious Mr. Perlman. We spoke briefly and I gave him my paper. Then I went downstairs to retrieve Mayer. “Chance of a lifetime,” I said. We hoped that Mr. Perlman would still be among the crowd, as the elevator was slow to arrive. He was, and as equally gracious to Mayer as he was to me.

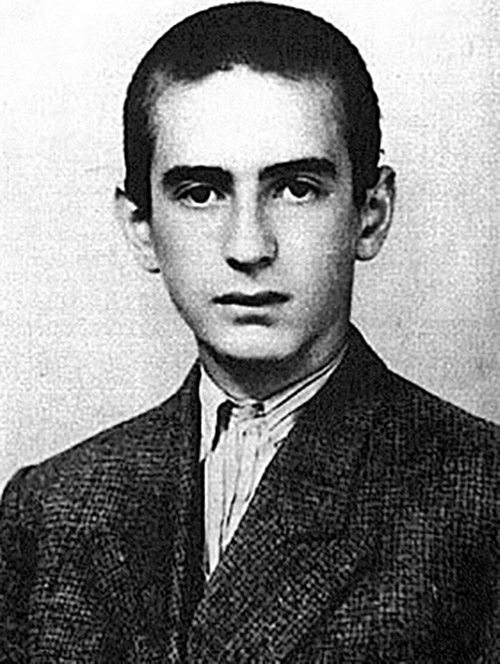

(Credit: WikiCommons)

Mayer and I waited for the elevator back to street level. When its doors finally opened, we were staring, stunned, directly into the faces of Elie Wiesel and his wife Marion. I soon realized that Mr. Wiesel, who had likely sought anonymity in a back elevator, was equally stunned. They were also heading for the less-trafficked exit.

What does one say when riding the elevator with a world renowned (and the world’s only) Nobel Peace Prize-winning Holocaust survivor? “Shalom Aleichem, Mr. Wiesel,” I blurted out. “This is my son Mayer.” My son offered his right hand. Mr. Wiesel nodded and extended his in a handshake. “Chanukah Sameach,” I wished them both. He returned the greeting. “Chanukah Sameach.” Then he and his wife exited the elevator for the stage door.

As we left the elevator, my son mused “It was worth coming—just for this.”

(Credit: 92nd Street Y)

It took minutes, or as it did with Mr. Wiesel, seconds, to spawn those life-affirming memories. A virtuoso and a visionary. A double header, I think, and a hard act to follow.

I had, to that point, thought of Elie Wiesel in abstract terms. I had read Night, with difficulty, and loosely followed his career. The name identification was enough; he was someone who quintessentially represented all the horror of the Shoah and the myriad, agonizing unanswerable queries and internal conflicts of its survivors—and their hopes. His was priceless work but so hard to digest without pain, although perhaps others have shared less subjective perspectives on his writing than I can muster at this point.

To commemorate his yahrzeit, the 92nd St. Y, which has an extensive repository of his talks, posted a video of Rabbis Avraham Rosen and David Ingber discussing the man, his spirituality and his legacy: (https://www.92ny.org/archives/remembering-elie-wiesel-on-his-seventh-yahrzeit?utm_source=SFMC&utm_medium=Email_Bronfman_EW_Yahrzeit_061523&utm_campaign=Bronfman_EW-Yahrzeit_061523&mcSID=929552).

The “Y” has archived Elie Wiesel’s lectures between 1967 and 2014, and this web page summarizes that legacy: “He constantly mined the Torah, Talmud, and the Hasidic masters to display where a Jew—really, where anyone—should turn for wisdom, inspiration, and challenge.”

Often, his lectures were part of a series that covered (in order), Tanach, Talmud, and Chassidism, followed by some reading/discussion of his own works. Rabbi Ingber shared a video excerpt from Professor (he was) Wiesel’s 1981 lecture on Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi, the Baal HaTanya, founder of Chabad Chassidus. It had taken close to two decades for that lecture to materialize, after much urging by Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the late Lubavitcher Rebbe Z”L. Elie Wiesel’s close, intellectually, and theologically honest relationship with the Rebbe began in the 1960s.

Dolinger (2016) explained how Mr. Wiesel sent the Rebbe his manuscripts in French and the Rebbe Z”L would give him feedback. He also provides a moving excerpt from their many discussions. On his first, nearly all night yechidus (individual audience), this transpired:

“Rebbe, how can you believe in God after Auschwitz?” Wiesel put to the Rebbe. “How can you not believe in God after Auschwitz?” replied Rabbi Schneerson.

“Rebbe, if what you say is meant as an answer to my question, I reject it. But if it is a question—one more question—I accept it.”

“That was an honest dialogue,” adds Dolinger. (https://www.jpost.com/opinion/elie-wiesels-masters-459689).

The conversations with the Rebbe were not always about theology. Mr. Wiesel recalled that:

“One day the Rebbe sent me a long letter about my attitude toward G-d. It concluded: “But now let us leave theology and speak of a personal matter. Why aren’t you married yet?”

Mr. Wiesel continues: “On the day of our wedding Marion and I received a superb bouquet with a card bearing his signature and his blessings.

He sent us an even more beautiful bouquet the day of our son’s bris.” (https://collive.com)

The questions, the despair, the hope, and the renewal were all packaged in the same persona of Elie Wiesel. May his memory be a blessing, and may his contributions be a bridge towards peace for all mankind.

Rachel Kovacs is an Adjunct Associate Professor of communication at CUNY, a PR professional, theater reviewer for offoffonline.com—and a Judaics teacher. She trained in performance at Brandeis and Manchester Universities, Sharon Playhouse, and the American Academy of Dramatic Arts. She can be reached at mediahappenings@gmail.com.