The professor works to uphold Jewish civil rights at Columbia University and beyond.

Jewish Link staff member and current Columbia University student Eliana Birman recently sat down with Professor Shai Davidai to speak about the current campus climate and what it may look like this year.

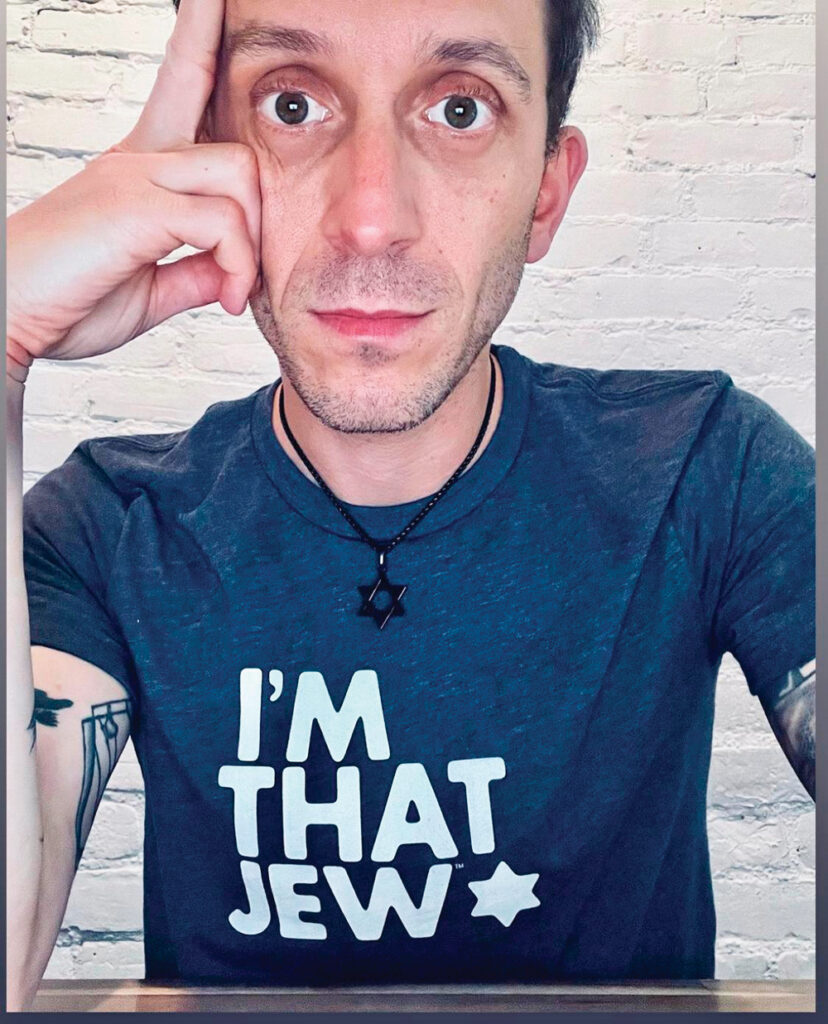

Davidai, assistant professor in the Management Division of Columbia Business School, became a prominent voice for Jewish life at Columbia last semester for his advocacy for Jewish rights on campus, specifically in the aftermath of the pro-Palestinian encampment and related antisemitism.

Davidai described his role of “advocate” as “horrible and incredible … the hardest thing I’ve ever done, and I’ve done some hard things in my life. It’s also the most fulfilling thing I’ve ever done, the most meaningful thing.

“A lot of people see me as some instigator and some provocateur, but I love that the campus has been quiet. It seems like at least nothing openly, blatantly is happening,” he said of the current climate. He shared his gratitude for the reduction of outward antisemitism and hate.

Davidai does not believe that this silence is a credit to the administration for addressing the root problem of antisemitism, but rather an immense increase in security measures. “We’ve basically become like Tel Aviv University or Jerusalem University, which closes its gates to the public because it’s afraid of actual terrorism, and here it’s because we’re afraid of terrorist sympathizers,” Davidai explained. Professors and administrators, like Dean of Columbia College Joseph Sorett, who have admitted to antisemitism, are also still employed at the university despite their statements. So far, though, Davidai believes “the year started off as it should, just focused on education.”

He expected the protests to happen on move-in day and the first day of classes this year, “like they were trying to show that they’re still here.” However, he believes that because 25% of the protesters from last semester graduated and the new students have yet to be indoctrinated, the movement is weak right now. That’s why there are teach-ins instead of protests, for the most part.

Reflecting on last year’s events, Davidai expressed unease for the coming weeks; with escalations in Lebanon and the approaching anniversary of the October 7 massacre. “We don’t know what’s going to happen when the protests stop being citywide and go back to universities, because what happened last year was they started in the city, right? So now, we’re seeing the students have a place to spew their hatred. They don’t need to do it on campus, which is great, because it’s the NYPD’s problem and not Columbia’s problem. But the hatred is still there. That, to me, is the scary thing.”

Davidai thinks that it should be “obvious” to the administration that no event that celebrates October 7 should be allowed to take place on campus, “just like no event that celebrates the Tulsa massacre should be tolerated on campus, and no event that celebrates the Pulse nightclub massacre.

“I think the incoming [Jewish] students … that chose Columbia or Barnard are like, the strongest of the Jewish students,” he shared. He appreciates that even students without a strong connection to their Judaism are taking pride. “We’re all Jews. Then some people become religious or don’t, but for me, it’s very simple.”

Davidai described the choice of students to wear Stars of David and yarmulkes as “a form of protest … carving out a space for us on campus, saying ‘OK, we’re here. We’re not being pushed away.’”

In talking about the actions of the faculty and administration, Davidai shared a metaphor he heard from historian and McGill professor Gil Troy—“educational malpractice.” Davidai said: “Columbia professors are not living up to their jobs as educators. As an educator, you’re not supposed to tell people what to think. You’re supposed to tell them how to think, and challenge them, and confront students’ one-sided views with an opposing view, not because you believe in it, but to help them hone their critical thinking-skills.” He sees these professors, especially in the humanities, as failed revolutionaries, “revolutionary wannabes” who are really just cowards. “It’s kind of heartbreaking, as a professor, to see how little brains it takes to be a professor here.”

After growing up in Israel, Davidai pursued his PhD in the United States because he was infatuated with the American higher education system—but that infatuation is long gone. “I thought that there was something unique about the people, and I realized there’s nothing unique about the people. All it takes to be a professor at Columbia, especially in the humanities and social sciences, is to write a dissertation. And in fact, it doesn’t have to be a good dissertation. It just has to be a dissertation that the hiring committee will agree with.” Davidai believes that professors should be able to say what they want, but it is unfathomable that some are saying things which will make students aware that “you’re openly, albeit somewhat indirectly, supporting terrorists that would target your students.”

What can American Jews outside of Columbia do to support Jewish students and faculty at Columbia and on all college campuses? Davidai made two points. First, diaspora Jews have been raised to believe that we do not deserve anything; we must work hard and be grateful for what we’ve been given. It is important to understand that “there are basic things we deserve, just like anyone else.” We deserve to congregate without the danger of being attacked and not be disproportionately targeted for hate crimes around the world. Second, Davidai urged Jews all across the US, regardless of whether they have family members in college or not, to “understand that the Jewish fight is their fight, because this is where American society trains…if they forfeit American colleges they’re forfeiting American society.”

On a larger scale, Davidai asks American Jews to realize this is not just a campus-centric issue, but a widespread civil rights issue. “No Jewish person, no matter wherever you live in the US, no matter how old they are, should ever think twice about whether they will be safe to openly and publicly be Jewish. Jews all around the country need to organize. They need to protest. They need to realize that this is their problem and it’s their responsibility, if not for themselves, then for the future generations.”

Davidai finds it inconceivable that believing in Israel’s right to exist is the “most cancelable offense” on campus right now. Believing in peace should be easy. This is “something that will be a dark mark on Columbia’s history for years,” he remarked. Davidai has a difficult time understanding the confidence that people have when siding with terrorism. “No one knows the entire story, and that’s OK because we have to keep learning and educating ourselves,” he said, but added that nobody should be so confident while being uneducated, “because even if you don’t know anything, the choice is between a democracy and a terrorist regime. Even if you don’t know anything about the conflict, just knowing how Israel treats its citizens and how Hamas treats the Palestinians in Gaza, it’s such a simple decision.”

Davidai has “paid a high price” in the fight against antisemitism, but would not change a thing. “I’m just grateful to be given the platform and the possibility to do something not just for our people, but for what’s right.” There are many days when he does not want to continue fighting, but seeing other people, especially students, fighting gives him the strength to continue. Davidai encourages everyone to join in, treating every day as day one. “Our fight here will not end when Israel’s fight ends, it’ll just shift into something broader. So we need every one of us to fight.”

Eliana Birman is the assistant digital editor for The Jewish Link. She is a student at Barnard College and lives in Teaneck.