The prophet Yeshaya (7:20) describes the downfall of Assyria, “On the same day shall Hashem shave with a hired razor that is hired (namely with them beyond the river with the king of Ashur) the head, and the hair of the legs: and it shall also sweep away the beard.” I am not sure that, on a pshat level, “Hashem” is intended. While YKVK is used in surrounding verses, here the written consonants are אד followed by ני, which could mean “my master / sovereign.” If Hashem is intended, did He really physically shave Sancheriv’s head, leg hair and beard? This seems degrading to Hashem’s honor; further, literal shaving implies a physical manifestation of the Divine Presence, which seems heretical.

An intelligent reading of Scripture requires understanding that some verses were intended allegorically by their author. Both the allegory and its interpretation are in the realm of pshat. Still, to understand the interpretation, we need to understand the plain meaning of the allegory. That is why Rashi, in his commentary to Shir HaShirim, will explain בֵאוּר מַשְׁמָעוֹ (the apparent meaning) followed by דֻּגְמָא שֶׁלּוֹ (the interpretive meaning). Rashi is fine with the phrase, “Let him kiss me with the kisses of his mouth” rather than providing only the interpretation of this verse as “Communicate Your innermost wisdom to me again in loving closeness.”

Rashi on Yeshaya mostly explains what each phrase corresponds to in the interpretation. The literal words, like וְשַׂ֣עַר הָרַגְלָ֑יִם / “leg hair” are mostly obvious. Still, Rashi makes two passes through the verse, and in the second, explains that אֶת־הָרֹ֖אשׁ to refer to the king, הָרַגְלָ֑יִם to refer to his camps, and הַזָּקָ֖ן to refer to his governors. Rashi then notes that Chazal, in the aggadah of Perek Chelek, say that the shaving is literal shaving (גילוח ממש), the beard removal is by singeing it with fire, and the beard is Sancheriv’s beard.

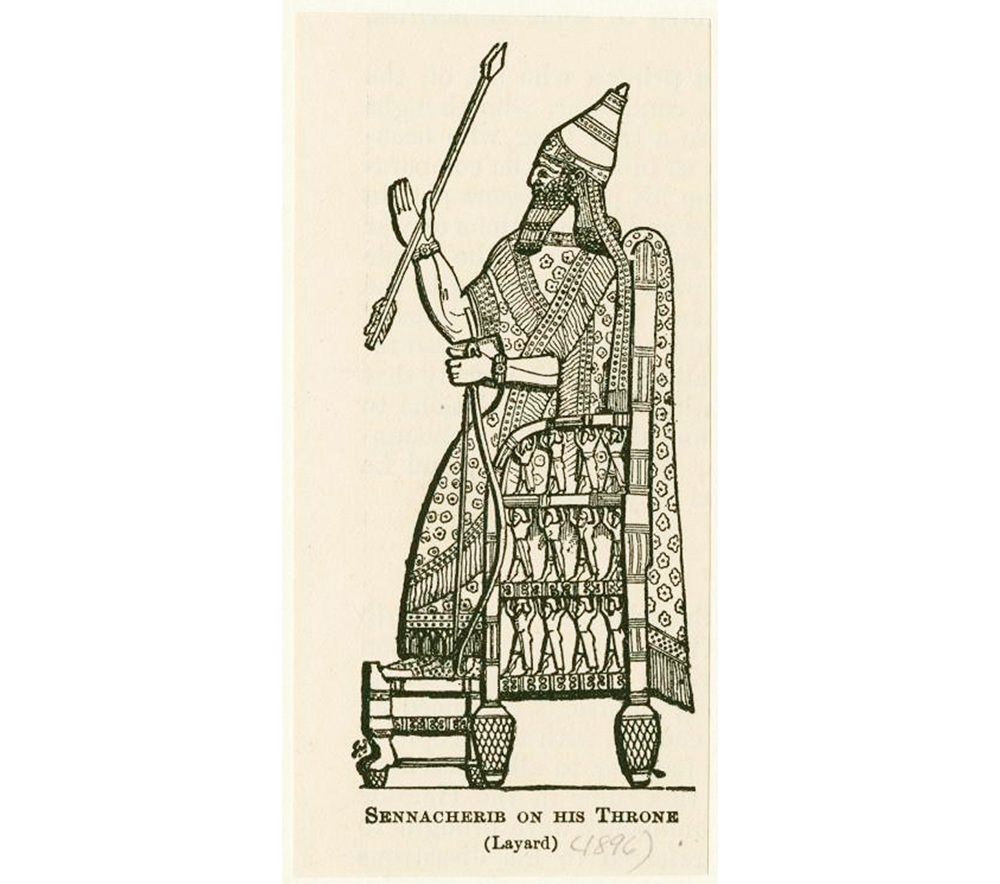

Rashi is referring to Sanhedrin 95b: “Rabbi Abahu said, Were this verse not written, it would have been impossible to say it,” then he cites Yeshaya 7:20. (Rashi on Sanhedin explains: “Hashem personally shaved Sancheriv.”) Hashem came and appeared to Sancheriv as an old man and asked him, “What will you say to the kings of the east and west whose children you brought and killed?” (For Sancheriv had brought 45,000 princes with him.) Sancheriv replied, “I also have that fear. What should we do?” Hashem said, “Go, change your appearance.” Sancheriv asked how, and Hashem offered to shear him. Sancheriv asked where to find scissors and Hashem directed him to a house. There, ministering angels appeared like men who were grinding date pits. He asked for scissors. They agreed if Sancheriv would grind a se’ah of date pits. He did so, and finally came back with scissors as it grew dark. Hashem told Sancheriv to bring fire for light. As he fanned it, the fire ignited his beard; it spread and sheared his head and beard, which the Sages said was the meaning of “and it shall also sweep away the beard.”

Rashi vs. Rambam?

Rashi on Yeshaya certainly takes the verse allegorically, and not that Hashem actually assumed human form or directed an avatar to literally shave Sancheriv’s beard. Still, what does Rashi think that Chazal meant? Does he think they meant their aggadah literally? We might suggest that he refers us to this aggadah in which they explain it in a literal manner— גילוח ממש— but then asserts that this aggadah, in turn, should be interpreted allegorically. This seems difficult to me, since Rashi himself understands that there’s a surface literal level of shaving, which is an allegory for something else. Chazal must be saying something different!

In his Ḥakira article, “Was Rashi a Corporealist?” Rabbi Natan Slifkin analyzed many of Rashi’s comments (though not the Sancheriv / beard one), including ones that don’t go out of their way to stress to readers the idea of Hashem having a physical form, including ones Rashi himself introduces, are to be taken not literally. Further, Ramban and other Rishonim write of the existence of great Torah scholars in France who were corporealists, so Rashi shouldn’t have taken for granted that his readers would assume otherwise. It is thus possible that Rashi was a corporealist, or thought (some of) Chazal were corporealists, even if it is a theologically unacceptable position nowadays.

Rambam, in his Mishna commentary, in the introduction to Perek Chelek, speaks of three groups who differ in their approach to Chazal’s words. The first group, the most numerous one, takes these aggadot literally with no esoteric meaning, even those ideas which are repulsive or push away the intellect and would cause some ignorant, and certainly wise people, to think poorly of Chazal. While these foolish people think they are honoring the Sages, they are, in fact, lowering them. They teach the aggadot of tractate Berachot and Perek Chelek (in Sanhedrin) literally. The second group, also numerous, also takes these aggadot literally and therefore mock Chazal’s words. The third tiny and scattered group understand that וכי הם בכל מה שאומרים מן הדברים הנמנעים דברו בהם בדרך חידה ומשל כי הוא זה דרך החכמים הגדולים—”Wherever Chazal spoke of impossible things, they were speaking via riddle and allegory, for this is the manner of great sages.”

I’d add that, from a literary perspective, the genre of the Sancheriv story seems one of allegory and esoteric meaning.1 Most details of a midrash should be deduced from a close reading of the underlying verses, and the trained reader can spot the Scriptural basis. Here, precise yet seemingly random details appear: Sancheriv fetches the scissors from a house, where he must work until nightfall by grinding a se’ah of date pits. Compare this to Rav Nachman of Breslov’s stories where random details appear because of the hidden message. I wouldn’t venture to guess the hidden meaning, because I don’t know Chazal’s mysticism, but I can appreciate its existence. Rather than being motivated by a midrash describing a theological or philosophical impossibility, I’d label a midrash as allegorical because of features intrinsic to the text.

Rambam’s Impossibilities

I don’t think Rambam is labeling every midrash as allegorical, and those who take any midrash literally as a fool. Rambam writes this as an introduction toPerek Chelek, which he singles out. This perek describes Hashem literally shaving Sancheriv, and Adam being 100 cubits tall (100a). Rambam references Brachot, which describes Hashem wearing tefillin (6a), Hashem praying (7a), or Og lifting up a mountain to throw on Israel, as well as a a 10-cubit Moshe taking a 10-cubit-long axe, leaping up 10 cubits and hitting Og on the ankle (54b) — the last being a midrash about which Rashba refers to Rambam’s opinion.

Rambam targets “impossible matters.” In his Ḥakira article, “On Divine Omnipotence and its Limitations,” Rabbi Yitzchak Grossman discusses how Rambam / other Rishonim maintained that “[Hashem] can do those things, and only those things, that are ‘inherently possible’ in some appropriate sense.” This excludes logical impossibilities, such as something being in two contradictory states at once (perhaps a cat in a box which is both alive and dead); mathematical impossibilities, such a square whose side equals or exceeds its diagonal (in Euclid’s geometry); and philosophical impossibilities, such as Hashem dividing himself or assuming human form.

The Dangers of Midrashic Figurativism

I expect that if Modern Orthodox students are exposed to this Rambam it’s not while studying medieval Jewish philosophy. It’s typically in a lesson where the teacher’s focus is showing that one needn’t believe every midrash aggadah. Because of this understanding of Rambam, I’ve seen students and teachers alike adopt a maximalist position of midrashic figurativism, the opposite extreme of midrashic literalism. Some maintain that no midrash aggadah was intended literally for we wouldn’t consider Chazal so unsophisticated. For others, a midrash is inconvenient, because they disagree with it, so they interpret it as figurative.

It’s an easy, but possibly not so intellectually honest approach. By saying Chazal didn’t mean the midrash literally, we empower ourselves to argue with midrashim. Personally, I think we (or Rambam) could argue with midrashim even if Chazal did mean them literally. If we require someone to say this first, we could explore Rav Shmuel ben Chofni Gaon and Rav Hai Gaon’s positions. Chazal or even medieval midrashic authors may have held different theological / philosophical / scientific backgrounds than us, where certain ideas are more plausible on a literal level. We can admit we disagree and then either back down or hold firm.

Here are some examples of well-known midrashim: Based on a juxtaposition of Avraham circumcising his household and Avraham sitting at his tent door in the sun’s heat, there’s a midrash (Bava Metzia 86b) that this was the third day after his brit, and Hashem was visiting the sick. The midwives in Egypt were Yocheved and Miriam, or Yocheved and Elisheva (Sotah 11b). Contra Rashbam, the brothers were the ones who drew Yosef from the pit (Bereishit Rabbah 84). Esther was jaundiced, but Divine grace was extended to her (Megillah 13a). Must we consider these midrashim as intended allegorically or make ourselves into fools?

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.

1 Yes, Rabbi Abahu introduces it with a “Wow, how astounding / heretical,” but I’d understand this as calling attention to it as a clearly allegorical description of Hashem’s actions.