In shul, after a person has completed his aliyah and is en-route to his seat, I am in the habit of congratulating him by telling him shkoyach, congrats. However, I restrict myself to doing this on Mondays and Thursdays. On Shabbat, I avoid doing so, taking my lead from Rabbi Yehuda HaLevi’s zemer (song) “Yona Matza,” which instructs: “Yom Shabbason ain liShkoyach1.”

Really, though, shkoyach is an informal way of expressing, as a hurried contraction, יְיַשֶּׁר כּוֹחֲךָ or יִישַׁר כֹּוֹחֲךָ. This was already a common expression in endorsing someone’s actions in Amoraic times, and Reish Lakish plays on this when, in Shabbat 87a and several parallel sugyot, he interprets Hashem’s referring to the tablets Moshe broke, אֲשֶׁר שִׁבַּרְתָּ, as יִישַׁר כֹּחֲךָ שֶׁשִּׁבַּרְתָּ, “congratulations that you broke it!” I wonder whether the derasha from אֲשֶׁר could indicate that a similar hurried contracted form was prevalent then.

The expression was also in use in Tannaitic times. In Yevamot 122b, someone witnessed the death of a man, and came before Rabbi Tarfon’s court (presumably in Lydda) to testify and allow the widow to remarry. When Rabbi Tarfon asked how he knew the deceased’s identity, the witness replied: We were traveling together on the road when a troop of soldiers chased after us. The man hung onto an olive branch and tore it off, then used the branch as a heavy staff to chase off the soldiers. Afterwards, I said to him, “Aryeh (lion), יְיַשֶּׁר כּוֹחֲךָ!” He said to me, “How did you know my name is Aryeh? That is what they call me in my city—Yochanan, son of Yehonatan, the Lion of the village of Shihaya.” Afterwards, he fell sick and died. On the basis of this testimony, Rabbi Tarfon allowed Yochanan’s widow to remarry. Regardless, we see shkoyach in use, interestingly in both cases for violent acts.

Our sugya, Gittin 14a-b, begins with a request from the sixth-generation Tanna, Rabbi Achi beRabbi Yoshiya regarding a goblet he had in Nehardea. As Rav Aharon Hyman describes, this Rabbi Achi’s father, Rabbi Yoshiya, was the famous Tannaitic colleague of Rabbi Yonatan, and was the leader of the city of Hutzal in Bavel. Rav Hyman is confident that Rabbi Achi took over his father’s place in Hutzal. However, he had business dealings with Nehardeans, and in Shabbat 152b, we see that he was buried in Nehardea—diggers digging in Rav Nachman’s land disturbed his grave, and he rebuked them.

In our sugya, Rabbi Achi asked Rabbi Dustai beRabbi Yannai and Rabbi Yossi bar Keifar, who were visiting Nehardea, to bring him back his silver goblet (to Hutzal). The Nehardeans turned over the vessel, but afterwards requested that the pair perform an act of acquisition in order to assume responsibility for any mishap that would occur in transit. The pair refused and the Nehardeans demanded the goblet back. Rabbi Dustai agreed but Rabbi Yossi refused, so they tormented him. Rabbi Yossi cried out, “see, master, what they are doing!” Rabbi Dustai said to them, טָב רְמוֹ לֵיהּ, which means “you are acting well; hit him” (Koren), or “Give him a good beating” or “this beating is well-deserved” (Artscroll), or “you are acting well in hitting him.”

When they came back to Rabbi Achi, Rabbi Yossi complained that Rabbi Dustai not only didn’t aid him, but even encouraged them, saying טָב רְמוֹ לֵיהּ. In an exchange with Rabbi Achi, Rabbi Dustai defended his actions, colorfully explaining how scary these Nehardeans were, and that he feared for his life. Rabbi Achai then agreed with Rabbi Dustai’s conduct.

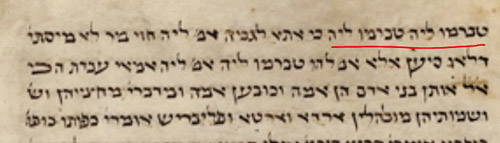

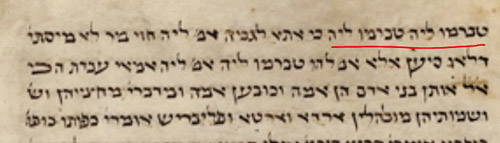

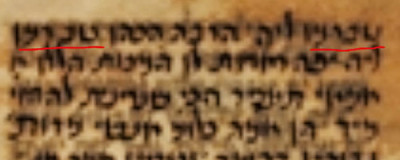

While our printed texts and several manuscripts have Rabbi Dustai beRabbi Yannai simply say טָב רְמוֹ לֵיהּ once, a few others (Girona, Oxford 368) have him repeat the expression. Also, Vatican 140 has it as a contraction, טברמו ליה טברמו ליה. That manuscript also has a small column of Rashi’s commentary, where the word also appears as a contraction.

Which variant is original? Are we dealing with accidental repetition (dittography) or accidental omission of a repeated text (haplography)? I would favor Vatican 140’s reading. The repetition correlates with the nature of the expression, one of (continuous) encouragement as they beat poor Rabbi Yossi bar Keifar. So too, the informal contraction makes it feel like a common expression egging on the violence. “Tavramu lei” is a contraction just like shkoyach! This might help us decide among the various interpretations proposed above, perhaps in favor of “beat him well!”

Finally, Nedarim 22b is worth mentioning. Ulla was traveling from Bavel to Israel, accompanied by two residents of Chozai. They argued, and one Choza’an arose and slew the other. He asked Ulla, “did I act properly?” Ullah replies in the affirmative, and with an expression indicating that he should follow through and deliver a kill stroke, אִין, וּפְרַע לֵיהּ בֵּית הַשְּׁחִיטָה. Ullah felt guilty about this. Upon arrival in Israel, consulted with Rabbi Yochanan about the possibility that he strengthened the hands of sinners. Rabbi Yochanan told him that he was acting out of self-preservation. Now, if the role of the expression is conceptually parallel, I’d assume that טברמו ליה means “beat him good!”

1 I can perhaps opt for the Sefardi equivalent, “Zabaru!”, a hurried chazak uvaruch.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.