As we explored last week, Bava Batra begins by discussing hezek re’iyah, literally damage by sight, and whether it is called “damage.” This isn’t literal damage, to be classified under nezek (as opposed to tzaar, ripuy, shevet and boshet). Rather, if we say that it is called “damage,” then privacy is a real concern, and one partner has a legitimate claim that they should build a barrier.

There is a stand-out example on Bava Batra 2b, in which the sight damage may actually be real. The gemara defends the proposition that privacy isn’t a concern, despite the Mishnah requiring a wall separating a garden. The defense is based on a statement of Rabbi Abba I, a second and third generation amorah from Bavel who ascended to the Land of Israel, and who traveled back. He had traditions from both Rav and Rabbi Yochanan. Rabbi Abba cited Rav Huna who cited Rav, that one is prohibited from standing in his friend’s field and looking at his crop when the grain is standing. The implication is that there is an ayin hara / eina bisha / evil eye concern, rather than a privacy concern.

The primary sugya from which this statement was drawn appeared recently, at the end of Bava Metzia (107b). Recall that all the Bavas were originally a single tractate. There, Rav Yehuda suggested that Ravin bar Rav Nachman not purchase land near a town, since Rabbi Abba1 quoted Rav Huna who quoted Rav, about this prohibition to stand in one’s friend’s field when the grain is standing. The Talmudic Narrator contrasts it with another statement of Rabbi Abba2. Namely, he encountered Rav’s students and asked them how Rav interpreted Devarim 28:3, “Blessed are you in the city and blessed are you in the field.” They responded that Rav said that your house should be adjacent to the synagogue, and your property should be near the city. He informed them that Rabbi Yochanan doesn’t interpret the verse likewise, and told them the alternate interpretation. The Talmudic Narrator harmonizes the sources by explaining that the proximity to the city is a blessing, in the scenario where he constructs a wall and partition surrounding the plot.

Does the Bava Metzia sugya require an ayin hara interpretation, rather than privacy? Nothing in the contrast and resolution requires it, though Rav Yehuda suggesting it as a concern when purchasing might indicate that the fear is of actual sight damage, rather than privacy. In Bava Batra, the Narrator certainly uses it to suggest real damage, rather than privacy. However, that’s to reinterpret the Mishnah about gardens, within a variant which Rishonim rule against. Without needing to resolve the Mishnah, who says the concern isn’t privacy, that people don’t appreciate others looking at their standing grain, for psychological or superstitious reasons, such that it is forbidden?

Extramission Theory

There are different ways to understand ayin hara. More mystically inclined people may have no problem with the idea that there are supernatural forces at work, and that looking at something with jealousy can harm it. I’ve heard explanations of ayin hara that, by acting in a way that provokes jealousy in others, Hashem will listen to their thoughts that the person doesn’t deserve it, thus invoking Divine Judgement. I’m not sure how this would work with a person violating Rav’s instruction, and standing in his friend’s field. Avoiding proximity to the city, as Rav Yehuda suggested, might be a means of humbly conducting oneself under the public’s radar. Also, see Teshuvot Rambam 48, where he explains that within the push-off in the rejected variant, the Rabbi Abba concern is one of pious conduct rather than law, and it seems that the impetus is psychological3.

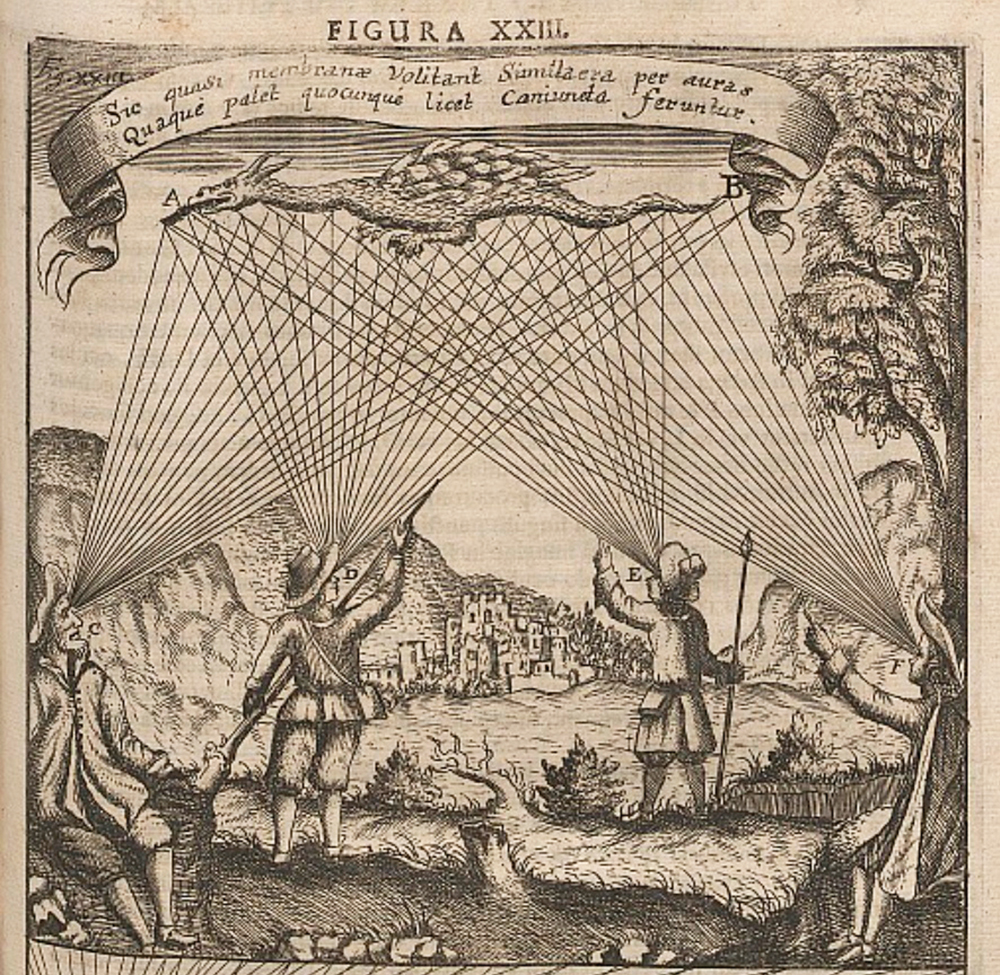

However, there’s a solid scientific basis for eina bisha in extramission theory. Ancient scholars debated how sight worked. Empedocles, Plato, Euclid, Ptolemy and Galen all believed that sight was made possible in part by rays that were emitted from the eye to the object. Aristotle disagreed with both extramission and intromission theory. Even within Aristotle’s theory, he wrote (in On Dreams, Part II) that a niddah could negatively impact a mirror by looking at it, and explained just how4. This Aristotelian idea about niddah is also advanced by Ramban on Vayikra 18:19. Similarly, Ibn Ezra on Shemot 20:1, in explaining Zachor and Shamor, invokes extramission theory to explain why the eye perceives lightning sooner than the ear hears the simultaneous thunder.

Though the extramission theory of vision is not scientifically accurate, that doesn’t matter when reading Tannaitic and Amoraic sources. Chazal believed in Torah U’Madda, and that one should believe contemporary scientific experts in determining halacha. Rav could have based himself on this inaccurate theory and worried about actual physical harm to the standing grain in that particular vulnerable state.

Blei Glissen

One real harm stemming from ayin hara, especially the more superstitious version of the belief, is how it can be a gateway to theologically fraught actions, which strike me as potentially darkei Emori and nichush. For instance, wearing the red string that is given out at Kever Rachel5. Tosefta Shabbat 7:1 begins, אלו דברים מדרכי האמורי… והקושר מטולטלת על יריכו וחוט אדום על אצבעו, listing tying a red string on one’s finger as a superstitious practice of the Emorites.

Similarly, the practice of blei glissen, German / Yiddish for pouring or casting lead, is used to detect and then remove the evil eye, strikes me as witchcraft or darkei Emori. As described in an Aish article6, “The Evil Eye Remover,” a practitioner heats lead on the stove to melt it, and pours it into a pan of cold water. She then interprets the shapes to indicate the presence of ayin hara. She then repeats the process, iterating until the ayin hara has disappeared.

Rav Shlomo Aviner was asked about this practice and he said it is’t mentioned in the Mishna, Gemara, Rishonim, Shulchan Aruch and Achronim, and should not be done. He also cited Rav Chaim Kanievsky’s opposition7. I’d add that we can find a source for this superstitious practice of molybdomancy (divination using lead, from μόλυβδος, “lead” + mancy) elsewhere. Wikipedia describes it as it is a non-Jewish tradition in “Austria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Germany, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Switzerland, the Czech Republic and Turkey.” In Germany, Austria, and Switzerland, Bleigießen (by that very name) is used on New Year to predict the fortune of the coming year.

In the US, the Pennsylvania Dutch also practice Bleigießen, In Pensylvania Dutch and Other Essays, by Phebe Earle Gibbons, we find the following: “CHARMS AND SUPERSTITIONS. Mrs. G., born in Lebanon County, says that when they were children one would take a looking-glass and go down the cellar stairs backward, in order to see therein the form of a future spouse. Another custom was to melt lead and pour it into a cup of cold water, expecting thence to discover some token of the occupation of the same interesting individual. A person in York also remembers that at Halloween her nurse would melt lead and pour it through the handle of the kitchen door-key. The figures were studied and supposed to resemble soldier-caps, books, horses and so on. This nurse was Irish, but the other domestics were German. A laboring woman from Cumberland County, and afterward from a “Dutch” settlement in Maryland, says that she has heard of persons melting lead to see what trade their man would be of. My German friend before quoted says that in the Palatinate they melted the lead on New Year’s Eve. In Nadler’s poems in the Palatinate dialect, St. Andreas’ night is the time spoken of for melting the lead. This is the 30th of November. Further, in a work called “The Festival Year” (Das Festliche Fahr), by Von Reinsberg-Duringsfeld, Leipsic, 1863, the custom of pouring lead through the beard, or wards, of a key is mentioned.”

Bilaam praised Bnei Yisrael in several ways. “How fair are your tents, O Jacob” (Bamidbar 24:2), in that the doors didn’t face each other, allowing for a measure of modesty and privacy. This is a motivating principle in Bava Batra (see Rabbi Yochanan, daf 60b). But, Bilaam also praised them saying (Bamidbar 23:23) that “there is no augury in Jacob, no divination in Israel.” May we incorporate both these values into our lives, and be tamim with Hashem our God.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.

1 See manuscripts; it is not Rabbi Abahu, entirely of Israel, quoting Rav.

2 And now, the contrast makes even more sense!

3 and that regardless, this is within the rejected Talmudic variant

4 “As we have said before, the cause of this lies in the fact that in the act of sight there occurs not only a passion in the sense organ acted on by the polished surface, but the organ, as an agent, also produces an action, as is proper to a brilliant object. For sight is the property of an organ possessing brilliance and color. The eyes, therefore, have their proper action as have other parts of the body. Because it is natural to the eye to be filled with blood vessels, a woman’s eyes, during the period of menstrual flux and inflammation, will undergo a change, although her husband will not note this since his seed is of the same nature as that of his wife…”

5 See https://aish.com/the-red-string-and-the-evil-eye/

6 See https://aish.com/the-evil-eye-remover

7 See https://hebrewbooks.org/pdfpager.aspx?req=56296&st=&pgnum=338 for more discussion and possible justifications