So you think only women value expensive footwear? Think again. A growing trend has been emerging in athletic footwear with prices that rival a Manolo Blahnik. This phenomenon, a buying, reselling and trading of sneakers business that gains a larger following each year, has its followers known as “sneakerheads,” and these secondhand-sneaker aficionados know their footgear. These shoes are not regular Nike or Adidas shoes that are available at the nearest department store, but rather pairs whose popularity was fueled by a sneaker release with an intentionally low supply, and sell for prices in the hundreds, and even thousands.

Sneakerheads are more than just people who like expensive shoes. They are connoisseurs of athletic shoes. They know which sneakers have limited inventory, which social media accounts to follow, how to bargain, where to score a sought-after pair and how to spot the occasional fake. Like any good collector, they can predict which shoes will become collectible even before they are released. One more detail about sneakerheads—while they can be any age or gender, it is an area dominated by teenage boys.

Popular sneakers—and acquiring them at any cost—is not something new to teenagers. When Nike released their much-hyped “Air Jordan” sneakers, they were coveted to the point of violence. The late 1980s and early 1990s brought sneaker competition to what Nike co-founder Phil Knight referred to as “insanity.” Today’s sneakerheads do not resort to such violent tactics, but their bargaining know-how and sales tactics can still be brutal.

According to Forbes magazine, the international sneaker market is a $55 billion dollar industry, with the major brands like Nike, Adidas and Under Armour amounting to over $25 billion of that total. The secondary sneaker market is more than $1 billion dollars of business, fueled by the teen business phenoms. What makes this a unique market is that unlike other “must have” items in fashion, and especially in footwear, teens seem less concerned about wearing the shoes than they are about actually acquiring them. Like all collectors, there are different types of sneakerheads. Some do choose to wear them, but many prefer to display them or eventually trade them in order to acquire the next deal or “must-have” item they find.

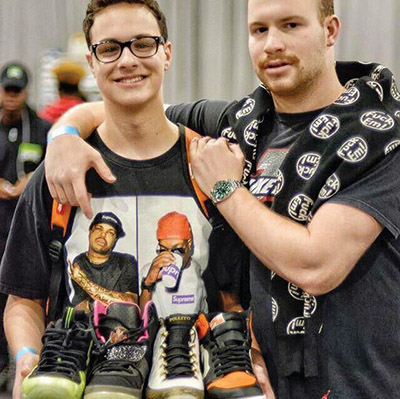

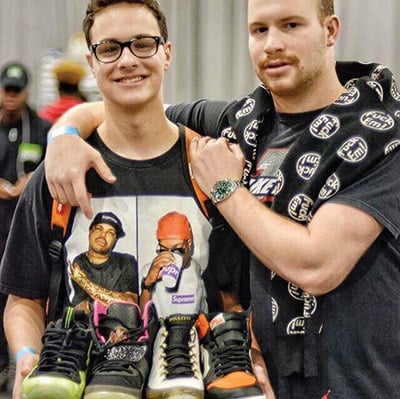

Sneakerheads even have their own convention: SneakerCon. Meeting at the Javits Center for an annual congregation of collectors, traders, buyers and anyone interested in limited sneaker collections is an important summit for this predominantly teenage crowd. After speaking to local teenage boys in the north Jersey community as well as to their parents, it is clear that this trend is here, too. One local high schooler, who prefers to remain anonymous, discussed his enjoyment of this business. “I like the fact that it’s something I can do to make money, and also that I have friends who are also into it,” he said. “This summer we went to SneakerCon together. I’m learning a lot about business, how to deal with people and how to work with different payment options.” He has also enjoyed learning about and predicting which sneakers will become popular. Sneakers follow the rules of economics, and a well-made sneaker with limited inventory and lots of buzz is almost a guarantee to be a solid investment, but this teenage businessman also explained that even sneakers with slightly more stock in circulation can still become a popular and sought-after pair “if there is a lot of buzz on Twitter and dedicated websites.”

Many wonder where such young not-even-adults find the funds for this expensive hobby. “They put aside bar mitzvah money, they work at Shabbat groups or other jobs, and save their money to be able to pursue their sneaker interests,” said one mother of a sneaker-collecting high schooler.

Sruli Fuld of Teaneck is a 12th grader at MTA and has been into the sneaker market since seventh grade. What started as an interest in sneakers, “scrolling through Instagram, seeing all these crazy pairs that my parents wouldn’t buy me,” has become a business venture and an active part of his life right now. He received his first pair of expensive sneakers as a bar mitzvah gift, which launched his interest. Following that, he bought his own pair of sneakers with the possibility of wearing them—and chose instead to sell them for a profit. Using the adage “You have to spend money to make money,” Fuld is using his profits to further invest in the next big pair. “When I first started I was extremely careful with my money, and buying maybe a pair a week because I didn’t want to invest too much money,” said Fuld. “Now I’ve learned that to make money, you must invest.” He also recommends going in with an idea of the intention for the sneakers. While his own personal collection is over 20 pairs, he goes into a sale knowing whether the pair will be to own or to sell. He even takes an extra precaution and tries not to buy in his own size in order to resist temptation.

Parent reactions to their sons’ business vary. Some parents are cautious and hesitant to support this expensive venture, others are openly disapproving, while some parents are happy to see their young son involved in an early exposure to business. While this is a high-stakes hobby, these parents do appreciate a life lesson their teens are learning firsthand—the approach to making important decisions and striking deals. This trend has been written up in mainstream magazines, covered on news channels and followed on websites. When ABC Nightline did a story of teen sneakerheads, one parent even said they have been impressed not just by the ability to score a find, but by their son’s knowledge of when to walk away, a sentiment echoed by any parent watching their child learn to make important decisions. As one teen said, “There have been pairs that I liked personally, but couldn’t bring myself to wear because the amount of money I can get for them was too high.”

In the meantime, the sneaker industry has gone from mere footwear to an art form: items are inspected for authenticity and sought after for rare editions. Experts cultivate an appreciation of the sneaker’s style and detail, and once acquired they either choose to keep it or pass it along to the highest bidder.

As Fuld explained from his perspective, “I’d rather have all my money in shoes and no cash in my pocket.”

By Jenny Gans