When Steve Kolb started his presentation at Netivot, he may not have known that it would move the head of school to tears. But that was just one measure of what his words and the small gift he offered meant to the school and the faculty.

Steve and Suzette Kolb of Highland Park are parents of two children who attended Yeshivat Netivot Montessori in East Brunswick, New Jersey. Steve is also the son of two Holocaust survivors. When he was looking to relate the life story of his father Herbert’s younger sister Erna, who perished in the Holocaust, and to share a unique possession of hers, he thought that both would be appreciated by the school. The head of school, Dr. Rivky Ross, agreed and scheduled Kolb to speak to an inservice day of the teachers on March 28.

Ross introduced Kolb, stating that the school was “so fortunate to be able to make the connection with the Kolbs” to hear their family story and to receive a book from the Holocaust era that the school can share with their students on Yom HaShoah next month.

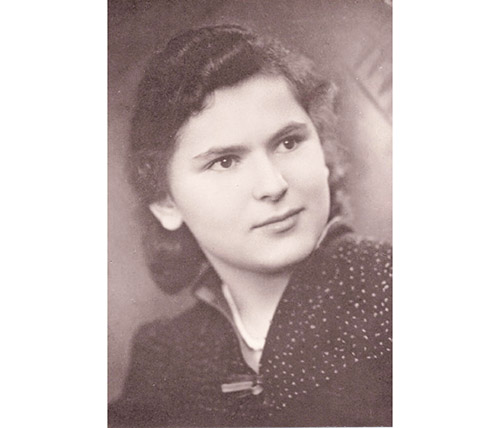

Kolb spoke about his father’s family, who lived for generations in Nuremberg, Germany before the war. His grandfather, Bernard Kolb, opened Juedischer Turnverein Nuremberg, the Jewish Gymnastics Club Nuremberg, which was later named Bar Kochba Nuremberg. Bernard also became the executive director of the Jewish Community of Nuremberg. He and his wife, Reta, had two children, Herbert (born 1922) and Erna (born 1923).

Conditions for Jews in Germany began to worsen in the mid- to late-1930s, with Jews being thrown out of the public schools, as both students and teachers. The pogrom of November 9-10, 1938, resulted in the destruction of all the synagogues in Germany. Jews were later forced to work in certain industries, and Herb worked in a book bindery shop while Erna and her boyfriend Julius Neuberger worked in a company that repaired pens. The companies that received conscripted Jewish workers were instructed by the German government to create separate entrances for the Jews so they would not mingle with the Aryans who also worked there. Jews began to be deported to the Theresienstadt ghetto in October 1941.

Erna and Julius married in October 1942, which was the last Jewish wedding held in the city of Nuremberg before the Shoah. In June that year two representatives of the Gestapo showed up at services on the second day of Shavuot and told those present that the congregation was being dissolved, its funds taken by the government, and the remaining Jewish families were deported to the Theresienstadt ghetto.

In the ghetto, Erna was assigned to a cleaning detail and occasionally worked in the bakery, where she could skim things and provide some extra food for her family. Herb, her brother, was assigned to a woodworking shop where he would take some extra wood pieces and fashion them into small toys, which he could sell and supplement the family’s food supply.

Teaching children was forbidden in the ghetto yet the Jewish administrators put teachers in charge of groups of Jewish children, to allow for informal education to take place. Both Julius and Erna found roles as caretakers of groups of children.

Erna became pregnant and she and Julius were optimistic, thinking that the war would soon end and life would return to normal. Yet the Germans deported the couple; Erna went to the Bergen Belsen concentration camp, where she and their child died, while Julius was sent to Auschwitz, where he died. Herb was used as a labor slave, as a carpenter, in other places. He and his parents stayed in Theresienstadt, where they were liberated by Russian soldiers in May 1945.

Herb spent some time after the war investigating the fate of his sister and brother-in-law and recovering artifacts from that period; in the following decades, he presented exhibitions in different areas on the Shoah and its impact on Neuberger and his family.

At the conclusion of sharing this family story, Kolb presented the book on education that his aunt had owned and which he was now sharing with the school. (He had not previously shared the book’s information with Ross). Kolb said that the book’s title was “Independent Parenting and Early Childhood,” and was printed in Germany in 1928; Ross and the faculty members gasped when Ross took hold of the book and noted to the teachers that the author of the book was Maria Montessori, the founder of the Montessori movement.

Kolb noted that, for him, this book underscored “the importance of teachers in our history, in the best and worst circumstances.” He added that it has always been an imperative in the Jewish community to both receive a good education and to give one to the next generation.

Ross stated that the story and the book represented “the idea of people dedicating themselves to education,” which she found very moving, adding with tears that “I cannot describe how meaningful this book is to our school,” and how it embodies the flow of history and the sacred work teachers do.

“What a moving and meaningful gift that Mr. Kolb has given this school,” said Suzie Foger, school counselor at Yeshivat Netivot. “Not just the physical book, but the gift of knowledge—of knowing that even through Holocaust, education knew no bounds. In a time when children may have felt powerless, this Montessori book given to someone in Theresienstadt focuses on empowering and following the child. We cannot wait to share this gift with our students.”

By Harry Glazer