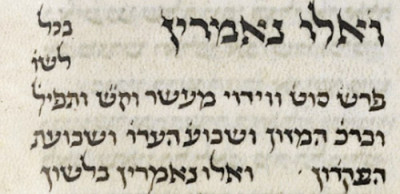

A new perek begins on Sotah 32a—with the mishna stating אֵלּוּ נֶאֱמָרִין בְּכׇל לָשׁוֹן—these may be said in any language. Yet, Rashi writes אלו נאמרין (בכל לשון) גרסינן, with the words בְּכׇל לָשׁוֹן in parentheses in our Vilna Shas. What gives? What was Rashi trying to say? How difficult is it to determine his intent when his girsological instructions themselves have girsological issues?

I suspect that there are two independent aspects of our text which vary: (a) whether there is a joining vav on the first word, thus וְאֵלּוּ; (b) whether the text is בְּכׇל לָשׁוֹן or בִּלְשׁוֹנָם. There are other, less pertinent features, such as whether נֶאֱמָרִים ends in a mem or a nun, and whether אֵלּוּ is spelled with an internal yud or without. These features can operate independently of one another.

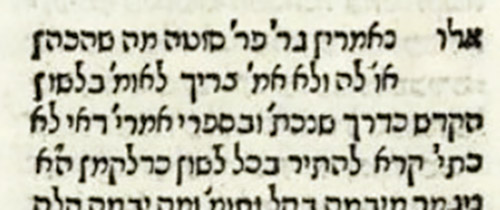

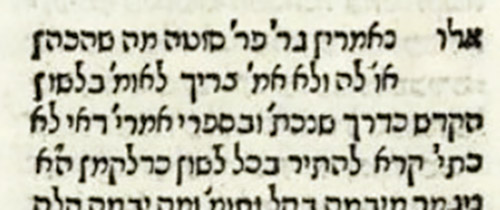

Thus, considering manuscripts of Talmud and mishna: Munich 95 has וְאֵילּוּ and בְּכׇל לָשׁוֹן. In contrast, Vatican 110 and Ktav Yad Kauffman (of Mishna) have אֵילּוּ and בִּלְשׁוֹנָם. The mishna in the Yerushalmi (and thus, also Ktav Yad Parma of Mishna) has אֵלּוּ נֶאֱמָרִין and בְּכׇל לָשׁוֹן.

Rashi had commented in favor of אֵלּוּ, which is how it appears in the Venice printing. This was was mistakenly taken as a comment about בְּכׇל לָשׁוֹן, which is why it appears as such in the Vilna printing, but with parentheses around it to denote that this is an error. I find this fascinating, because we are operating on a meta level here—dealing with variant texts in text about variant texts.

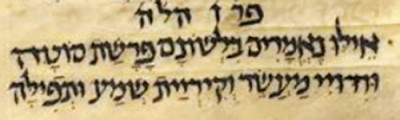

Perek Title Preserves?

To gather support for one reading or another, we could examine how it appears in sources discussing it, namely Gemaras which cite quote and discuss it (Shevuot 39a, Brachot 40b and Yerushalmi Sotah 7:1), though we would also need to examine manuscripts—there is often disagreement there. We could also examine Rishonim and how they either channel the text (in Rif and Rosh, though there’s no such commentary on Sotah) or how they quote the text in a dibbur hamatchil or in a discussion.

Don’t worry, I won’t bore you with too many details and leave this as an exercise for the reader. There’s possibly an inconsistency here. For instance, Rosh to Nedarim 9:2 speaks of פרק ואלו נאמרים in Sotah, and commenting on Tamid 33b writes ובפרק אלו נאמרים.

About a decade ago, in order to promote academic approaches to Talmud study, I told a very frum friend about a very neat textual variation taught to me by Dr. Zvi Arie Steinfeld, in a mishna in Ktav Yad Kaufmann in Shabbat 2:5: רבי יוסי פוטר בכולם חוץ מן הפתילה שהוא עושה פיחם, missing מפני but inserted in the margins—where this original girsa correlates well with a dayka nami by Rava1. My friend’s response was that a variation in this text was highly unlikely, since religious Jews have the custom of reciting “bameh madlikin” on Friday night, so this was a highly visible text. This isn’t so persuasive, given many variations in nusach hatefillah itself.

Still, אלו versus ואלו is a variation in a perek title itself. It is interesting that the text varies even here. Perhaps, it varied even before Rishonim approached it. Two other examples of this phenomenon. The fourth perek of Bava Metzia is HaZahav in Bavli and HaKesef in Yerushalmi. Bavli’s mishna begins הזהב קונה את הכסף הכסף אינו קונה את הזהב—“with gold or silver acquiring the other,” based on the primary currency. In Israel, the roles of gold and silver were reversed. The last perek in Nazir is “Hakuttim,” but prior to censorship, the title was “Hagoyim.”

Why Care?

Are these variants distinctions without a difference? For וְאֵלּוּ versus אֵלּוּ, the difference might be whether the mishna is a continuation of the preceding mishna—just as this difference is made in interpreting verses—and whether they begin a new topic. For comparison, why does the first verse in Shemot begin וְאֵ֗לֶּה שְׁמוֹת֙—with Ibn Ezra explaining it as a continuation of an idea of the end of Bereishit? Sometimes, a jarring initial vav could result from a transfer or splicing from some other Tannaitic source—if we could find one. We might make an analogy to the first verse of Shemot, taking it as a deliberate echoing of Bereishit 48:8: וְאֵ֨לֶּה שְׁמ֧וֹת בְּנֵֽי־יִשְׂרָאֵ֛ל הַבָּאִ֥ים מִצְרַ֖יְמָה יַעֲקֹ֣ב וּבָנָ֑יו. We should examine other such mishnayot, such as Makkot 3:1, ואלו הן הלוקין, and consider their basis. Here, it might be a deliberate or accidental echoing of the next segment of the mishna, וְאֵלּוּ נֶאֱמָרִין בִּלְשׁוֹן הַקּוֹדֶשׁ.

As for בְּכׇל לָשׁוֹן versus בִּלְשׁוֹנָם, consider Tosafot, who adopt בִּלְשׁוֹנָם—meaning “in the language they can understand,” each person in his own language. This would exclude a Median who doesn’t speak Persian, yet hearing it in Persian. Had it said בְּכׇל לָשׁוֹן, it would imply whether the person understood it or not, which Tosafot says is not something the Gemara implies.

Let’s direct our attention to Yerushalmi Sotah 7:1. It excerpts the mishna as אֵילּוּ נֶאֱמָרִין כול׳. Further, it cites a dispute between frequent disputants, Rabbi Yoshiya and Rabbi Yonatan—the fifth-generation students of Rabbi Yishmael—who don’t appear in mishna, about why the verse states “the Kohen shall say to the woman:”

כְּתִיב וְאָמַר הַכֹּהֵן לָאִשָּׁה. בְּכָל־לָשׁוֹן שֶׁהִיא שׁוֹמַעַת. דִּבְרֵי רִבִּי יֹאשִׁיָּה. אָמַר לֵיהּ רִבִּי יוֹנָתָן. וְאִם אֵינָהּ שׁוֹמַעַת וְלָמָּה הִיא עוֹנָה אַחֲרָיו אָמֵן. אֶלָּא שֶׁלֹּא יֹאמַר לָהּ עַל יְדֵי תּוּרְגְּמָן.Rabbi Yoshiya employs the term בְּכָל־לָשׁוֹן—in any language,” but continues to qualify that as שֶׁהִיא שׁוֹמַעַת—that she understands.” Rabbi Yonatan responds that “if she doesn’t understand, why is she saying ‘Amen?’” Rather, the Kohen has to say it to her directly, and not via a translator. I’m not sure that Rabbi Yonatan disagrees that she must understand it, for he notes that she is saying “Amen.” Rather, Rabbi Yonatan’s concern is what to do with the phrase in the verse, וְאָמַר הַכֹּהֵן לָאִשָּׁה.

Regardless, Tosafot’s idea is explicit in the Yerushalmi. Despite this, they have בְּכָל לָשׁוֹן. I’d suggest—contrary to Tosafot—that Rabbi Yoshiya’s usage shows that this phrase is fine to convey the idea, and we need not shift the girsa. Indeed, Tosafot’s very concern could be what influenced someone to improperly adjust the text to בִּלְשׁוֹנָם.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.

1 I wrote a summary of the idea at https://scribalerror.substack.com/p/charred-wicks