In his New York Times bestselling book “Moonwalking with Einstein,” author Joshua Safran Foer discusses the way in which the modern reader encounters texts; namely, we read (articles, books, product descriptions) in order to gain knowledge we do not already have. Re-reading a text that one has encountered numerous times before feels monotonous and unproductive. Foer analyzes the change from our ancient relationship with text, in which manuscripts were so rare that when a text was read and discussed it not only usually occurred in a communal setting (the idea of “silent reading” was almost nonexistent), but the texts being read were usually something like the Bible or an almanac, something with which the readers were already highly familiar.

Communal readings were less about obtaining knowledge and more like a “concert” experience—a powerful recitation of a tribe’s communal language. The weekly communal Torah reading (which Foer mentions in this context) often reminds me of the struggle that we as modern Jews experience as we read the weekly Torah portion along with the communal reader. Until now I have found that I am left either joining the communal, familiar voice of the reader in the group experience, or losing the common text entirely as I engage in the added knowledge of some private reading of commentators, thematic introductions, or external essays on the portion’s themes.

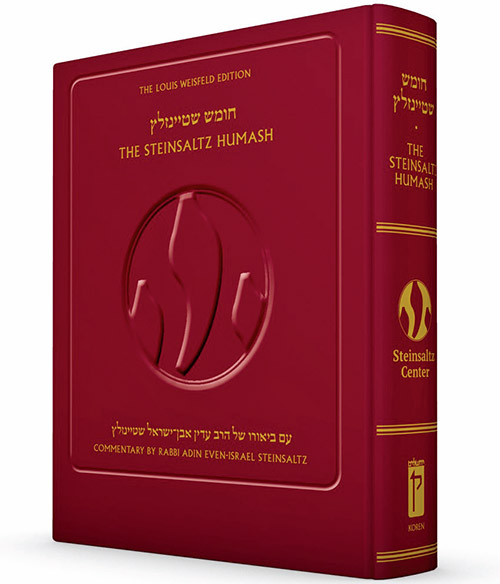

Koren Publishers calls its recently published Steinsaltz Humash a “pioneering translation and commentary on the Torah,” which seeks to “remove any ‘barriers’ to the text, connecting us directly to the ‘voice of the Torah.’” Rabbi Steinsaltz also emphasizes in his introduction that “this work does not aspire to be revolutionary or novel,” but rather “seeks to offer the reader the plain meaning of the text…to enable the ‘voice’ of the verses to be heard.” I would argue that this new work is actually quite revolutionary, precisely in the way in which it allows that “voice” to be heard; namely, in how Rabbi Steinsaltz’s translation and commentary allow the reader to pursue the discovery of something novel in their understanding of the text, while simultaneously following the “voice” of the traditional reading.

The format of the English translation places the translation to the right of the text (it actually appears on the right-hand page of the book in traditional Koren style), provides the literal translation of the Torah verses in bold, but weaves in an additional translation, not bolded, that allows for a smoother understanding of the verse, without resorting to lengthy detached commentaries. For example, in this week’s Torah portion of Noach, Chapter 8, verse 11, the translation reads:

“The dove came to him at evening time, after it had been sent off in the morning, and behold it had plucked an olive leaf in its mouth. Since olive leaves are relatively tough, they did not rot in the water. And Noah knew that the waters had abated [kallu], that they had become light [kal] and diminished from upon the earth.”

This translation (similar to what Artscroll did in their Talmud translation) allows the reader to easily differentiate between the literal biblical text and which are supportive commentary. One “simple” translation manages to offer contextual background, quote the commentary of the Ramban (a small endnote to the source citation is included) and provide a brief etymological lesson, all effortlessly combined in the “p’shat” translation. This fusion of text and commentary enables a valuable reading of the text, but I would argue that it is especially valuable when the text is being used during kriat haTorah. It allows the shul-goer to follow the text at a given pace, along with the communal reading, while simultaneously opening the text to deeper understanding. In this way, this commentary will definitively add something particularly fresh and innovative to the synagogue experience.

An additional aspect of this translation is the commentary at the bottom of the page, which divides into two categories. While there are discussion notes that include collections of midrashic and philosophical ideas (thematically related and brief), most of the commentary provides clarity on the cultural, etymological and geographical abstractions in the text. There are a number of simple colored maps throughout the Humash, elucidating military strategies as well as travel and trade routes. Species of flora and fauna mentioned in the text are accompanied by annotated images that also discuss the geography of the Land of Israel. The colorful photographic imagery accompanying the discussion in the Book of Leviticus about kosher birds and fish is supported by notes such as that on Leviticus 11:16, which translates “shachaf – שחף” as “seagull” and provides the etymological background for the translation, the location of the bird’s habitats near water sources in Israel, and the nature of its webbed toes, which is what lands it on the list of forbidden birds. This model of attaching the descriptions in the text to the geographic realities, archeological findings and etymological history mimics the well-known Da’at Miqra commentary, but in doing so not only makes this type of valuable textual reading accessible to English speakers, but actually does so in a more concise way. As promised, the text itself is the main attraction. The common focus of the translation and the accompanying commentary is in how they function as a “voice” of the text, or as R’ Steinsaltz puts it, “a barely perceptible screen rather than a heavy concealing coat of armor.

The commentary’s division of the Torah portions into thematic units, each with a short introduction, also allows for the reader to experience this text as a guide to the reading of the Torah—as its conductor and illustrator—so that the encounter with the text feels fresh and new, while the shul-goer still feels anchored in the communal reading. Whether you’ve heard or seen this text a thousand times before, or are coming at it for the first time, this new Steinsaltz Humash will elucidate, and contribute to, that encounter.

The Humash can be purchased on the Koren Publishers’ website and retails at $44.95. Translations are by R’ Joshua Schreier and reviewed by Rabbi Dr. Joshua Amaru.

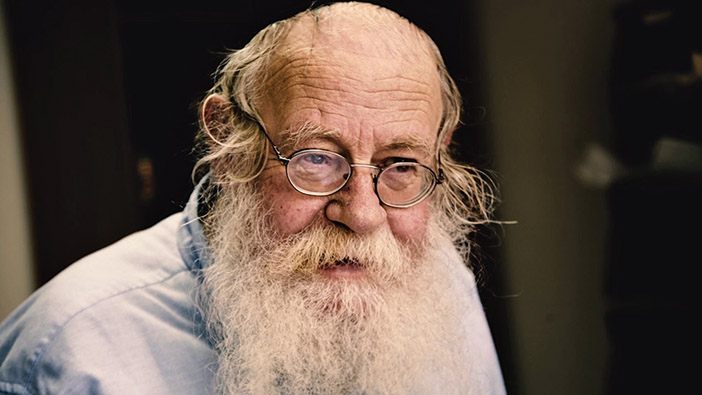

By Miriam Krupka Berger

Teaneck’s own Miriam Krupka Berger is dean of faculty and former Tanach Department Chair at the Ramaz Upper School in Manhattan.