The holiday of Sukkot is flavored by two distinctly different mitzvot. The experience of four minim is the most aesthetically pleasing mitzvah and the arrangement is the only object referred to by the Torah as “hadar,” or “lovely” and attractive. Each of the four elements references a different feature of nature, and each item conjures multiple layers of imagery. The most famous interpretation of this arrangement associates the various species with different human body parts: the etrog is heart-shaped while the leaves of the aravot resemble human lips. Presumably, these species underscore the beauty of the human form as well as the religious potential latent within each anatomical component. Many other themes and symbols are embodied in this unusual bouquet. The colors are striking, the aromas enticing, and the entire experience adorns Sukkot with beauty.

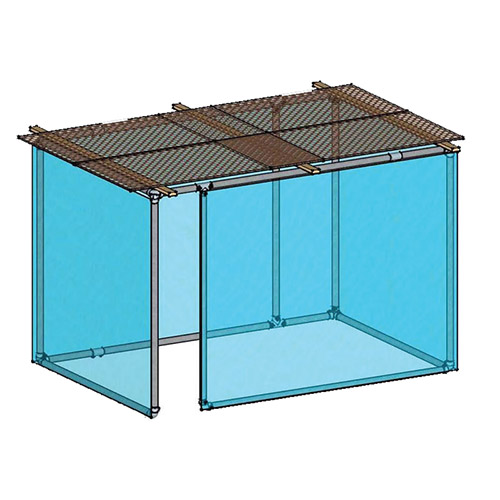

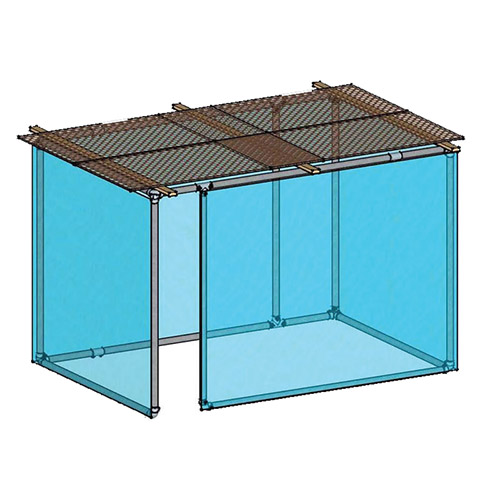

Strikingly, the sukkah itself is portrayed very differently from the four species. The Torah schedules the mitzvah of residing in the sukkah during the period of gathering grains and manufacturing wines: “b’aspecha migarnecha u’miyikvecha.” Based on this time stamp, the gemara (Succah 12a) infers that the “s’chach” roof of the sukkah must be manufactured from agricultural leftovers—the materials that are typically discarded during harvest and during wine-making such as husks, shells, twigs and branches. As a result, the s’chach must include only organic, non-manufactured items. The sukkah is defined as a “leftover,” manufactured from surplus and discarded materials, which have little obvious aesthetic or even functional value. As opposed to the four minim, which are exquisite and even lavish, the sukkah is constructed from spare parts held together by duct tape. It is this rudimentary hut that houses the Divine presence.

This profile of a sukkah illustrates the value of economization. We are often drawn to the “expensive” or the “attractive” and we ignore potential in items that aren’t flashy or colorful. Economization, or not wasting material, reminds us of potential in all items and, of course, by extension, the potential in all people. Yaakov conducts a daring nighttime dash back across the river to reclaim a few small and worthless vessels. Already prodigiously wealthy, he can well afford to discard those vessels and avoid the hostile wrestling match that ensues. Yet he values all items and doesn’t waste or discard his possessions.

Valuing rather than discarding teaches us to identify previously unrealized potential in items and people we often overlook. If a sukkah can be fashioned from “spare parts,” what other pursuits in life can be enabled or advanced through resources that aren’t immediately obvious? Which people in our lives don’t immediately grab our attention but are invaluable resources in our quest for meaning and for meaningful relationships? How can we build sukkah-like towers from the shells and twigs in our world?

Beyond the value of economization and recognizing potential in everything surrounding us, the sukkah confers the trait of resourcefulness,or the ability to make “do with less.” We are often challenged to succeed without ideal resources at our disposal and in imperfect conditions. Sometimes we are challenged due to material shortages—lack of funds, manpower or other abilities. Can we still succeed when facing these compromised situations? How do we fare when the shortages aren’t material but psychological, medical or emotional? How do we perform when we are tired or when our health is ailing? Are we successful and poised when stressed or otherwise emotionally strained? All these situations demand resourcefulness and resilience—the ability to utilize “spare parts” and to perform under less-than-ideal circumstances while still fashioning a “sukkah.”

This personal and communal challenge of resourcefulness is even more acute in the modern context in which we live more comfortable and resourced lives than in past generations. We easily purchase the goods and services to make our lives more comfortable and we live generally more “padded” lives. However, there is great skill in getting by with less, and without that skill we are often hampered in life—particularly when facing more constrained situations without the easy availability of necessary or ideal “resources.” The ability to function and to succeed with less is a vital skill and sometimes atrophies in conditions of comfort and abundant resources.

The mitzvah of sukkah showcases the untapped potential within our surroundings and within ourselves. Often this potential lies in the objects in our lives that are not flashy and are easily ignored. Similarly, we often overlook quiet people who can deeply enrich our experience. The mitzvah of sukkah also demonstrates that success isn’t always a product of greater resources. In fact, sometimes more is less and less is more.

Rabbi Moshe Taragin is a rebbe at Yeshivat Har Etzion, located in Gush Etzion, where he resides.