The year was 1977. Israel was still recovering from the trauma of the 1973 Yom Kippur War and the spirit of the country was at a low. Tensions were high as the Cold War marched on. Israel was facing boycotts from its Arab neighbors and the Soviet Union. The Jewish state was in need of a morale boost.

At the same time, a basketball team named Maccabi Tel Aviv that had never won an international title was beginning to raise eyebrows and advanced all the way to the semifinals of the European Champions Cup, widely recognized as the top competition in Europe. It was February 7, 1977, and Israel was set to play against one of the top teams in the league, CSKA Moscow, the basketball team representing the Soviet Union. The Soviet team was favored to win against the underdog from Tel Aviv.

The Soviet Union had ties with Arab countries and had broken all diplomatic relations with Israel. The country did not allow its sports teams to play in Israel and refused to host Israeli athletes. Concerned that playing against Israel would infuriate its Arab friends, the Soviet Union tried to keep the game as low-key as possible and scheduled the semifinals in a small town in Belgium called Virton. The stadium held 500 people, and almost every seat was filled by an Israeli or Jewish person who attended the game to support Maccabi. This was more than just a basketball game: It was an ideological battle that pitted the Jewish state, with under 4 million inhabitants at the time, against the Soviet superpower, with 260 million inhabitants.

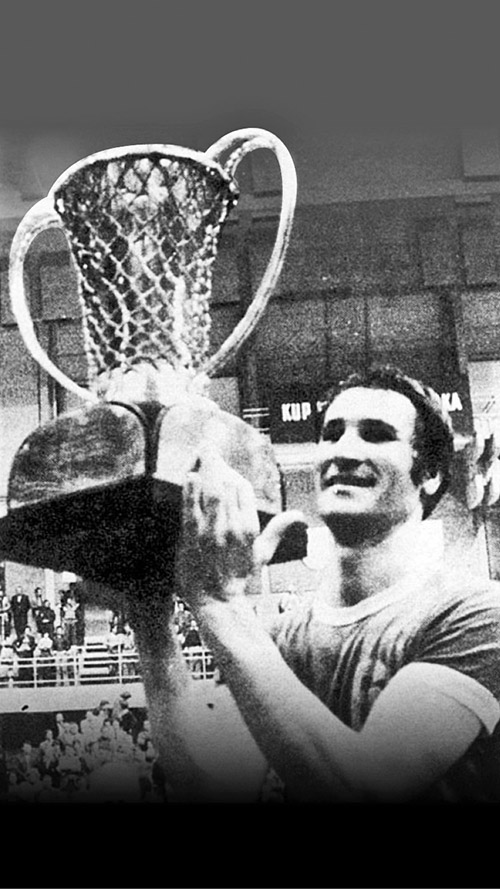

That evening, most of Israel’s population was glued to the sole TV channel at that time, as they watched with great excitement as Israel’s national basketball team claimed a 91-79 victory over the Soviet team. In Belgium, an elated crowd erupted in song and dance on the basketball court, surrounding the Israeli athletes in a joyous hora dance and chant of Am Yisrael Chai. In the middle of the chaos, a young player lifted the cup in his hands and in a heavy American accent shouted into the microphone—“anachnu al hamapa, ve’anahnu nisharim al hamapa!”—“We are on the map and we are staying on the map…not just in sport but in everything.” This phrase rang in the ears of millions of Israelis who were witnessing this scene on their TV screens and lifted their spirits. It was just what the country needed. Maccabi Tel Aviv would continue on to beat Italy’s Mobilgirgi Varese by one point and clinch its first-ever European Champions Cup title.

After the victory over the Soviet team, some 150,000 excited fans—including many Israelis who had never watched a game of basketball before in their lives—greeted the athletes back in Israel. Many eyes were on the American who captured their hearts a few nights earlier with his inspiring phrase. The name Tal Brody began to become a household name in Israel, and it was becoming known that this American implant was one of the primary factors behind Maccabi’s rise to success.

Brody’s illustrious basketball career began in Trenton at the city’s JCC. By the age of 9, he was already playing in three different basketball leagues. At age 21, after graduating from university, he was picked 12th in the NBA draft, no small feat for the Jewish young adult from New Jersey. During that summer, Brody flew to Israel to take part in the 1965 Maccabiah Games, also dubbed “The Jewish Olympics.” Team USA brought home a gold at the games in basketball, thanks in large part to Brody’s talent.

Brody made an impression not only on the fans, but on the chairman of Israel’s national basketball team, Maccabi Tel Aviv, who approached Brody with an offer to remain in Israel for one year and to help take the team to another level. Until that point, Maccabi had never advanced to any major international competition. The country was also suffering from economic

recession and facing boycotts, and the chairman of Maccabi was sure that Brody would help lift the spirits of the country. The NBA was waiting for an answer from Brody, but he couldn’t resist this challenge. “What’s the big deal putting one year on hold?” Brody thought.

At the same time that Brody was helping Maccabi rise in the rankings, he was becoming more and more tied to the Jewish state. He was witnessing the power of basketball to uplift not only the Israeli spirit, but also Jewish communities in Europe that were dealing with antisemitism, yet gained so much pride watching Brody and his teammates compete around Europe. No other team was forced to deal with the same security protocols that Maccabi faced and though the team faced many threats, it kept picking up wins. Brody was beginning to understand that so much more was at stake than just a basketball title. He decided that he would continue to represent the fledgling Jewish State.

“It meant a lot because you know you are part of the nation of Israel, you are part of the history of Israel and you want to continue that history,” Brody explained. “When you see as an athlete what happens in the world it gives you side energy that you want to compete against this and correct it and do what you can to set things straight. Our way of doing this is competing against the European countries as a way to fight against hate of the Jews.”

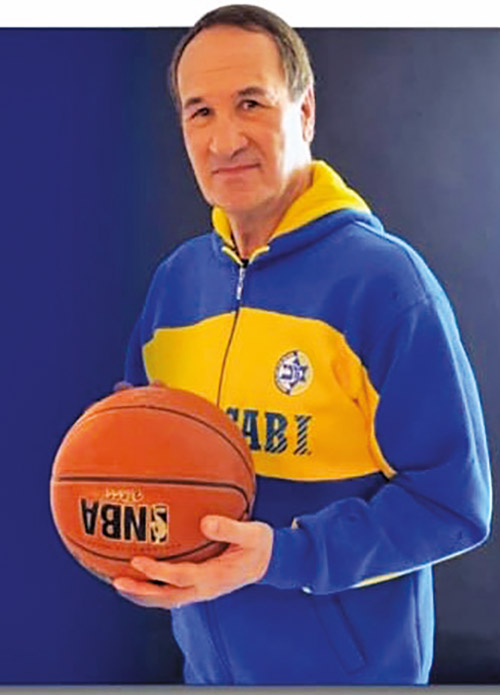

Brody’s athletic highlight was no doubt the victory in 1977. Since then, Maccabi has won another five European Championships, the most recent one coming in 2014. Today, Brody is involved in another battle, fighting BDS and antisemitism. He serves as Israel’s first Goodwill Ambassador, a voluntary position in Israel’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs that was bestowed upon him in 2010 by former Minister of Foreign Affairs Avigdor Lieberman. Brody brings the same passion he had on the court to his mission today to spread a positive image of Israel around the globe.

In his role, Brody has visited Brazil, Mexico and China, meeting with delegations and sharing his story. He travels with Israel’s sports delegations and meets with authorities in different countries to educate them about the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) definition of antisemitism, which often comes in handy when fans shout antisemitic slurs at Israeli athletes.

But Brody spends most of his time where he thinks the battle is the most fierce and needs the greatest attention: North American college campuses. “There is a lot of misinformation out there,” Brody said. “And Israel’s public diplomacy is not budgeted.” He brings a story of Israel that so many students never hear in their dorm-room discussions or college classes. He also shows “On the Map,” a 2016 film that tells the story of Maccabi’s heroic victory in 1977. “For those students on campuses [this film is] a game changer because they don’t see Israel in this light,” Brody said proudly.

Brody does not only spend time educating non-Jewish audiences about Israel. He travels the country on behalf of many Jewish organizations, most notably the Jewish National Fund. Brody believes that there is just as much work to do with Jewish audiences as non-Jewish ones. “You need to see Israel to feel Israel,” he asserted. “The more these groups come to Israel, when they go back home they are filled with love for Israel. They see what Israel is and there’s not a better thing that can happen in order to fight antisemitism, hate against the Jews and divestments.”

Looking back on his rich life, Brody can list many milestones that he is proud of. In 1979, he became the first Israeli athlete to be awarded the country’s prestigious Israel Prize, the highest civilian honor. He was listed by the New York Times among the top 10 immigrants that influenced Israel. In 1996, he was inducted into the international Jewish Sports Hall of Fame and, in 2011, he was inducted into the United States National Jewish Sports Hall of Fame.

“As a young kid from Trenton, New Jersey, all his life he wanted to play professional basketball. And when I had the opportunity at my doorstep, I was able to be strong enough and say you know what, this is important in a different way and I’m going to take up that challenge and go to Israel and see if I can make a difference.” That kid from Trenton rejected the NBA in order to lift the spirits of an entire nation. Five decades later, he is still bringing pride to his people. And he certainly put Israel on the map—for good.

Alisa Bodner is a Fair Lawn native who immigrated to Israel a decade ago. She is a nonprofit management professional who enjoys writing in her free time.