Tamir Goodman’s unique career path stems from his love of basketball and humanity, professionalism and integrity, and skills dealing with special needs and diverse children. He has served war-weary communities traumatized by family disruption and displacement. His faith, his wife Judy and family, friends, and mentor Coach Chaim Katz (Baltimore’s Talmudical Academy [TA]) strengthen him.

Dyslexia didn’t hinder Goodman’s ranking as the U.S.’ 25th best high school basketball player or his “Jewish Jordan” Sports Illustrated cover story. It increased his empathy and respect for diversity and taught him early on about basketball’s capacity to empower. On Sundays at TA, special needs students practiced with the team; afterwards, they ate pizza together.

Goodman finished Takoma Academy, a mostly African American Adventist high school, and played for Towson University, where his roommate was Muslim. He competed with basketball pros from around the globe. When his professional career ended, Goodman, convinced that the game is a “holy vessel” and “… an incredible tool to empower and unite,” set out to do just that.

Basketball’s Immediate and Multifaceted Impact

Goodman recognized that sports build physical strength but also transcend the physical, and so determined to intertwine them with chesed, deeds of kindness, wherever possible. After 10/7’s initial shock passed, he harnessed basketball’s power to help children cope with displacement, fear, depression, and inertia. “It’s so therapeutic. They smile, they can feel better about themselves, they can establish new friends…and they can take their mind off negativity…the benefits are instantaneous,”

There is a huge miklat (shelter) in “Baka, right near a basketball court.” Goodman announced on social media that “we’re going to try to empower the kids.” Within a couple of hours, over 100 boys and girls appeared. Tearful parents and grandparents thanked him for getting the kids out of the house and smiling again. Goodman practiced walk throughs with the kids to ensure that they could reach the miklat in 30 seconds or less, and then get back to the court. US basketball magazine Slam picked up the story. Before long, thousands of displaced kids, relocated in Jerusalem hotels, were clamoring to play basketball.

(Credit: Yehudah Halickman)

Goodman called on his friends in Athletes for Israel, whose Jewish and multiculturally diverse members fight racism and antisemitism. They, and other donors, provided funds, equipment, and clothing for kids from Israel’s South who fled home with nothing. Goodman went with friends to hotels and brought these children to play. Each hotel has a social worker, and the clinic works through them. Given children’s extra-emotional state now, he says, additional sensitivity is needed. When a child is struggling and upset on the court, Goodman will go to him, softly suggest minor changes in technique or positioning and consequently, lift the kid’s spirits and attitudes to life.

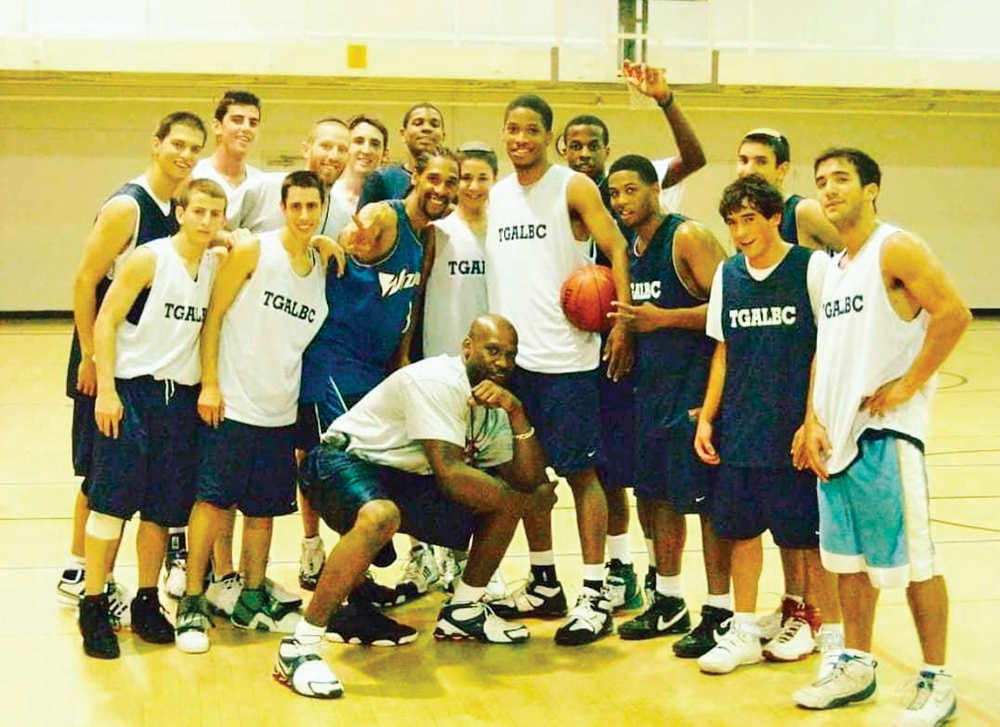

As the South settled down somewhat, Goodman and volunteers ran clinics at residential homes for special needs children, who have spent the war separated from their families. Goodman’s friends at Athletes for Israel and Project Max (another non-profit fighting racism and antisemitism) Former NBA championship star Eddy Curry, a celebrity “first” for these kids– led clinics in Raanana and Sderot. “To see these kids’ faces and know what they have gone through, it was like magic…”

During Curry’s visit to the Nova site, a siren went off and he entered a shelter. Ex-Knicks player Michael Sweetney, Goodman’s friend since high school, has also assisted at clinics; plans are pending to bring another NBA player soon.

This week, Goodman will travel to Sderot, where two basketball hoops will be secured to the outside of a large shul that doubles as a shelter. If a siren goes off, children playing can just run inside, but thankfully, this hasn’t occurred thus far.

(Credit: Tamir Goodman)

The Art of Running Disparate Clinics During Wartime

Each of Goodman’s clinics serves 50-100 children, male and female, ages 8-17, some co-ed, and some, like the residential homes, single gender. Many children’s issues are challenging and superimposed on an already exceptionally emotional year in Israel. Compared with previous years, his current projects represent “a heightened shlichut” (outreach activity). “We’ve got to do this…we’ve got to reach as many kids as possible… that’s the holiness of basketball. That’s why Hashem (G-d) gave me basketball in the first place.”

I inquired if such programs exist for adults, for anyone who might be feeling ‘burnout.” Goodman tries to include people on missions or parents who accompany their children. After 10/7, some parents hesitated to bus their children to clinics, but that discomfort subsided. Positive feedback about the clinics has been accompanied by tears of joy.

Goodman gets the manpower needed to manage this from friends and players, both Americans and Israelis, and some on missions, who volunteer to coach. One boy volunteered as part of his bar mitzvah celebration. “People like to give back in different ways,” Goodman says. His cohorts’ chesed, and that of volunteers, is through sports.

In addition to the residential clinics, the inclusive, heterogeneous groups are not one off. Goodman’s basketball friends, friends and colleagues, help by staying in touch with clinic “grads.” There are locations that have been hit hard, near migunitim (mini-shelters) and could still use hoops. As no one knows from day to day how things will go in Israel, Goodman sees basketball, which empowers, as fighting an unknown with a known.

An Overriding Goal: Increasing Unity Within Diversity

Goodman’s 2007 multicultural camp set the precedent for Unity Camps, camps and clinics that unite black and yeshiva kids together on the court. He has organized camps in Baltimore, Indiana, Utah and Chicago and currently runs them four times a year, including November and December on the East Coast. For now, in Israel, the focus is on day-to-day achievements, helping participants feel like they can “win the day.” It’s difficult to think far ahead.

Even Goodman’s entrepreneurial interests align with “basketball as empowerment.” PJ Library will soon publish his book on being dyslectic. He is Director of Sports Relations, Fabric, which sponsors Unity Clinics. For his company, Aviv Sports, he designed and manufactured the first antimicrobial-moisture-lock net, which also provides advertising opportunities.

In all things basketball, Tamir Goodman has followed his late father Karl’s mantra—“Let Your Game Do the Talking” and basketball’s empowerment speaks loud and clear worldwide.

Rachel Kovacs, PhD, who teaches communication at CUNY and Judaics locally, is also a PR professional, freelance writer, and theater reviewer for offoffonline.com. She trained in performance at Brandeis and Manchester Universities, Sharon Playhouse, and the American Academy of Dramatic Arts. She can be reached at mediahappenings@gmail.com.