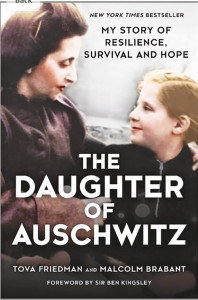

One of the youngest survivors of Auschwitz, Tova Friedman, spoke to a broad cross-section of the Highland Park community on the evening of Thursday, January 5, at the Highland Park Public Library. The packed room had audience members sitting on the floor when even the arrival of additional chairs could not meet the demand. Friedman’s recently published memoir “The Daughter of Auschwitz: My Story of Resilience, Survival and Hope” was listed on the New York Times bestseller list shortly after its release.

The genesis of the book was a chance meeting with co-author Malcolm Brabant during the reunion of Auschwitz survivors at the 75th anniversary of the camp’s liberation. Brabant got in touch with her during the global COVID-19 lockdown, and they worked together to create the book. Initially unsure of whether to write a book, the overwhelming positive reaction to the first chapter led her to continue the effort.

Valeri Drach Weidman, the library’s coordinator of circulation, introduced the program as part of a series featuring local authors, calling the book one of the “most powerful memoirs I’ve ever read.” Friedman opened her presentation by noting that she usually speaks about her experiences to strangers and it was unusual to see so many friends and neighbors in the room.

Born in Poland in 1938, Friedman’s earliest memories were of sitting under a table in the ghetto of Tomaszow Mazowiecki. Being under the table was a practical place to be: it would keep her from being seen if the Germans entered the apartment, as they would have killed her on sight.

“I saw only legs,” Friedman recalled, and learned from an early age to stay quiet and stay inside. The times Friedman was able to look out the window, all she saw were corpses on the street.

Her parents did not “sugar coat” what was going on; Friedman knew to listen to what they said and follow rules to stay alive. Hearing that someone “wouldn’t be back anymore” translated to their having been killed by the Nazis. The doctors were killed, allowing sicknesses, such as cholera, to run rampant through the ghetto, thereby “killing the people the Germans had not gotten around to.”

From 1940 to 1942 Jews were forcibly moved to the ghetto. The numbers from Friedman’s town alone are startling. A community of 15,000 Jews before the war was reduced to only 200 after liberation; only five children survived of the several thousands of children in the community.

Friedman noted that she “represents a town and a way of life that doesn’t exist anymore. I’m talking for those who aren’t here” to speak for themselves.

The German methodology was to break apart families by killing the young and old, and continually move the able-bodied to other locations to instill fear and prevent connections from being made that might lead to resistance. The constant “selections” added to the unease and separation. To this day, the word “selection” triggers all sorts of negative emotions for Friedman and she has a tremendous fear of German Shepherd dogs that were trained to attack Jews trying to escape.

The ghettos were being liquidated by 1943, with the remaining residents being shipped to concentration camps. Friedman discovered after the war that “Christianity saved her” from immediate extermination. As she was a child, upon arrival she would have been immediately sent to the crematorium. It was apparently a Sunday when she arrived, and the Nazis were observing their holy day after six long days of killing Jews. The reprieve meant she could continue hiding, this time in the barracks. She learned to differentiate the sounds of the footsteps of the various Gestapo members and the sounds of the different guns that were fired. Her mother took her to the public executions of the Jews the Nazis wanted to punish and was told that if she behaved there was a possibility she would survive.

At the start of 1945, Friedman could see that the Nazis were trying to liquidate the camp while leaving no records that anything untoward had happened there. Her mother did not feel she was strong enough to take on the forced march the Germans were preparing for and asked her daughter if she would be able to be “alone” after the war. They agreed that it would be better to die together than be separated. Friedman’s mother hid her daughter in a bed with a corpse in it and told her not to even breathe. She stayed completely still, and then found it even harder to breathe because of the smoke entering the room from the buildings the Nazis burned to destroy the evidence. Her mother came to retrieve her and together they walked to the camp gates after the Germans had all left the camp.

Sadly, after being a pillar of strength during the war, her mother was unable to continue on in freedom after the loss of her immediate and extended family (parents, grandparents and approximately 150 brothers, sisters, nieces, nephews and close cousins, all of whom were exterminated by the Nazis). She died at age 45 in America, unable to move beyond the loss.

Amazingly, Friedman grew up to be a social worker, therapist and academic despite not having formal schooling until age 12.

The audience was riveted by Friedman’s life story of deprivation and indestructibility.

Marilyn Berger of Highland Park had heard so much about Friedman’s experiences and wanted to hear more. “I don’t know anyone who was a child during the Holocaust and here we have one in our own backyard.”

“It is amazing that her mother saved her from going on what certainly would have been a death march as the camp was being liquidated,” said Hadassah Geretz of Highland Park. “This is the second time I have heard her speak and the details she shares speak volumes.”

A common theme during the Q & A segment was how survivors could go on after all that happened to them. Friedman answered that her healing was helped by rebuilding families and having the goal of the establishment of the State of Israel. “The pain is less when you have more children” and grandchildren. The lost family members are never forgotten, but having new ones helps.