The year was 1940. The place was the calm waters of the Irish Sea. The German U-boat captain carefully took aim. In the crosshairs of his periscope was an unescorted British troop transport. He took pride in the fact that he never missed. When he assured himself that his helpless prey would be easily sunk, he let fly with his first torpedo. The torpedo sped to its target, hit the ship, but failed to explode. The captain cursed silently to himself and immediately prepared a second torpedo. Taking special care to line up the path of the missile to the middle of the helpless ship, he called out “Fire two.” Hundreds of passengers on the deck watched in horror as the torpedo bore down on the ship. Right before the torpedo would have made contact and sunk the ship and all of its passengers, a wave miraculously lifted the ship and the torpedo passed harmlessly below it. The captain of U-56 could not believe what he saw and ordered the submarine to submerge.

The Voyage of the Dunera

The year was 1940 and many Jews had successfully found refuge in England. Many, like my father, Willy Bauman, were lucky enough to be sent on the Kindertransport from Germany and Austria and were adopted by Jewish families in England. The British took in 70,000 refugees and treated them compassionately. However, in May of 1940, Germany invaded France, Holland and Belgium, and a wave of fear engulfed the British public about a German invasion of England. The reason for the German success in Europe was attributed to a cadre of German civilians in the invaded countries that served as a fifth column. In a decision that was later described by Winston Churchill as “a deplorable mistake,” thousands of German-speaking foreign nationals in England were rounded up and deported. My father and others were placed in a camp and given the choice of being deported overseas or remaining in internment camps in England. Since the British were preparing for a German invasion many refugees opted to leave England and avoid Nazi capture. The largest group of deportees was assembled in Liverpool and on midnight of July 10 the HMT Dunera set sail. Not one of the passengers knew their destination.

The ship had a normal capacity of 1600 passengers but was crammed with 2000 mostly Jewish refugees, aged 16 to 60. My father was 18 at the time. Along with them were German POWs, 200 Italian Fascists and 261 German Nazis. The ship’s crew was composed of British criminals who had been incarcerated. They were offered pardons if they volunteered for this dangerous mission. They were a coarse lot that took special joy in mistreating the passengers.

The 57-day voyage was a nightmare. The lower decks were jammed and men slept on the floor or on tables. Dysentery was rampant and seasickness was a constant problem. There were only ten toilets available. Food consisted of smoked fish, sausages, potatoes and a spoonful of melon and lemon jam a day. The bread was usually maggoty and the butter rancid. The upper decks, the only source of fresh air, were out of bounds and barred by barbed wire and sentries with bayonets. The cruel guards threw all personal items including vital medications, siddurim and tefillin overboard.

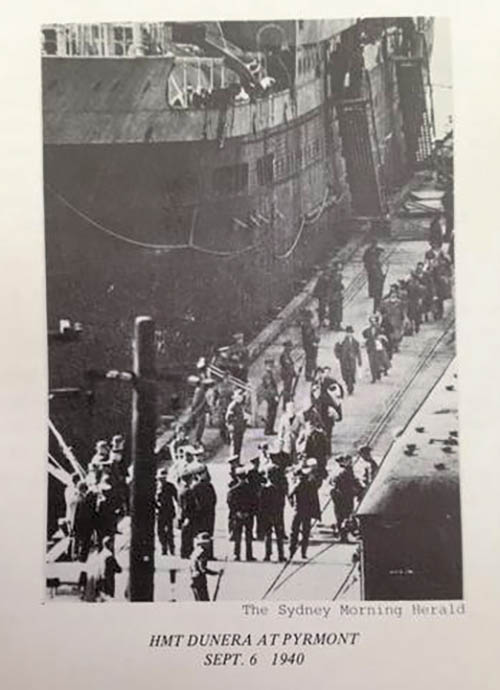

At the end of the harrowing journey, on September 3, Rosh Chodesh Elul, the ship docked in Melbourne, Australia, where the Nazis and Italians were removed and sent to their camps in Tatura. The ship then proceeded to Sydney where the Australian armed forces took over. Expecting a shipment of captured enemy soldiers in uniform, they were surprised to encounter a bedraggled lot of refugees from Hitler. The Aussies immediately sized up the situation and realized that the British had made a huge mistake. Appalled at the treatment of the refugees, they gave the emaciated internees food packets, fruit and cigarettes and took them by train to a detention camp that they had prepared in Hay, a small town of New South Wales in the Australian outback.My father recalls seeing kangaroos hopping alongside and keeping pace with the train. Hay was in a sparsely populated, desolate, hot and arid area that was teeming with sand flies. Life was uncomfortable and difficult.

In that camp, my father and the other refugees organized a community. Many of the internees had been highly educated in Europe and a makeshift university was established. Lectures and debates on a wide variety of subjects including economics, literature, language, geography, agriculture and more were conducted. A kosher kitchen was established and a shochet prepared the kosher meat. Lively discussions were common as to how best organize their limited autonomy. Money was printed as was a newspaper called The Boomerang. My father took art lessons from a noted artist. He worked in the kitchen and came under the influence of many pious German Jews. A Haggadah was mimeographed after being written down from memory. That Haggadah has become a much sought after item for collectors of Judaica.

After Pearl Harbor, under pressure from the House of Commons, the British decided to reclassify this group as “friendly aliens” and freed them. Travel back to England was very dangerous so hundreds volunteered to join the Australian Army. Many of those who did make it back to England enlisted in the British armed services.

My father chose to work on a farm, known in Australia as a “station,” that was owned by Reb Moshe Feiglin, a Lubavitcher Chassid. Reb Moishe had emigrated to Australia many years previously and founded a self-sufficient Jewish farming community. My father picked fruit in the orchards and eventually found his way to Melbourne where several cousins resided. My father then became active in setting up youth programs, camps and teaching in Hebrew school until he was able to come to the States and join his parents in Shreveport, Louisiana in 1947.

The Hand of Hashem

Around the year 1980 the captain of U-Boat U-56 died. As was the custom, the captain’s logbook was opened to the public. An amazing story then came to light.

After the failed attack, the captain waited for dark. The sub surfaced to replenish its air supply. Several crew members then reported that the Dunera had jettisoned items overboard. The captain’s curiosity was piqued. On the sea’s calm surface he found several valises. He brought them aboard, and to his surprise he found clothing with labels from German stores. He also found personal letters written in German. Jews in England who wrote to their relatives wrote in German and omitted any Jewish references so that their mail would pass the censors. The captain therefore believed that the ship was full of German POWs. Months before, the Andora Star, another British transport ship, this time full of German and Italian POWs, was sunk by a German U-boat. The uproar in Germany was great and all German U-Boat captains were warned not to repeat this mistake. The captain of U-56 radioed to all nearby U-Boats not to harm the Dunera. He then escorted the ship.

As the story became public, the survivors of the attack realized that the hand of Hashem helped them that day. The vile lot that comprised the crew took their ire out on the poor refugees by tossing overboard much of their belongings. However, if not for that act, 2000 Jewish lives would have been lost.

The Aftermath

The Holocaust years saw many lives lost and many others were deeply affected by what they had seen and suffered. The way the survivors lived out their lives reflected their experiences. Countless communities in Europe were lost forever. However, many communities in the US, Israel and even Australia were enriched by the survivors. Many of the “Dunera Boys,” as they were referred to, became very active in Australian society. They contributed to the arts, music, business and many other fields. For years, their annual reunion was covered by the press and most Australians readily acknowledged the contributions of the Dunera Boys. My father, Willy Bauman a”h, learned about Torah and Mitzvos in the Australian outback. He also learned about what it takes to build a community. He spent the rest of his life participating in and delivering shiurim and in helping to make Englewood into the bastion of Orthodoxy that it is today.

By Dr. Ira Bauman

Dr. Ira and Laurie Bauman are members of the Beth Aaron community of Teaneck. Dr. Bauman practices dentistry in Keyport, New Jersey. They are blessed with children and grandchildren who live in Seattle and Lakewood.