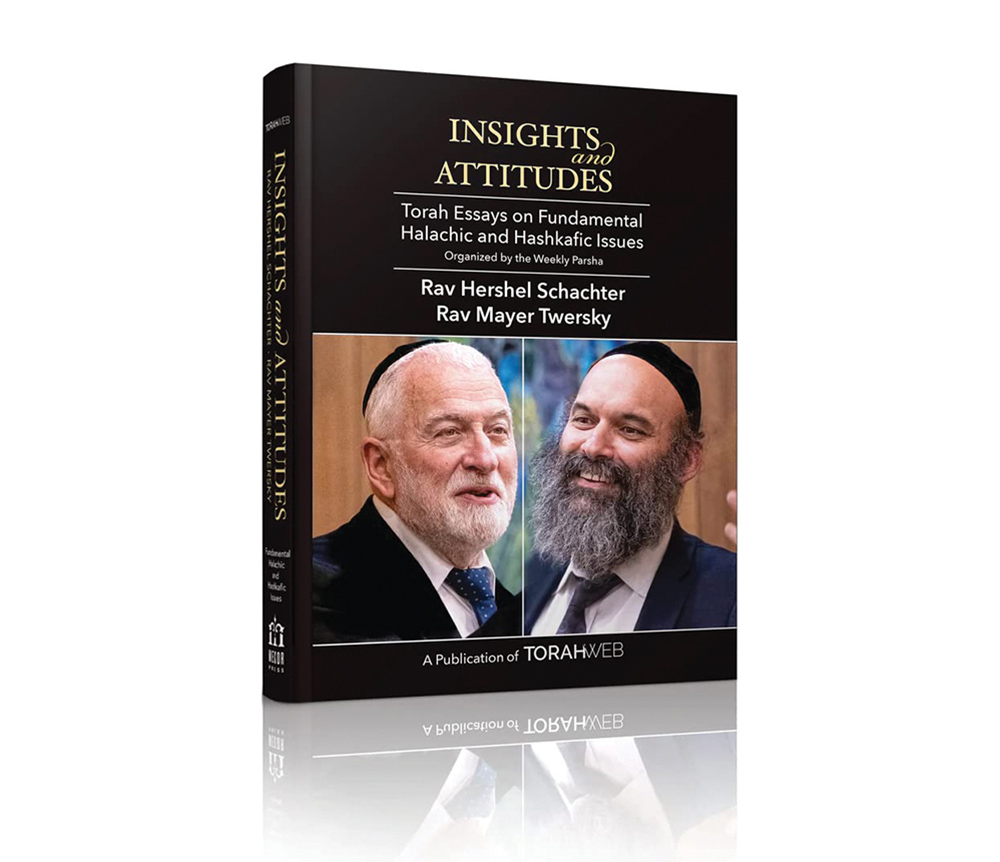

Editor’s note: This series is reprinted with permission from “Insights and Attitudes: Torah Essays on Fundamental Halachic and Hashkafic Issues,” a publication of TorahWeb.org. The book contains multiple articles—organized by parsha—by Rabbi Hershel Schachter and Rabbi Mayer Twersky.

At the very end of Chumash Bamidbar, the Torah relates that the leaders of shevet Menashe came to Moshe Rabbeinu with the following problem: because Tzelafchad had no sons, his estate would be inherited by his daughters. The shevet of a child is determined by the shevet of his or her father, so if Tzelafchad’s daughters were to marry someone from another shevet, their husbands’ shevatim would take possession of Tzelafchad’s portion of Menashe’s land when Tzelafchad’s daughters’ children inherit their mothers’ property, and thus, shevet Menashe would lose part of its share in Eretz Yisrael.

In response to this problem, HaKadosh Baruch Hu tells Moshe Rabbeinu that—as a hora’as sha’ah—any single girl who inherits land in Eretz Yisrael must marry a boy from her own shevet. This halacha only applied through the 14th year after Yehoshua bin Nun crossed the Jordan river. The Navi tells us that it took seven years to conquer all of Eretz Yisrael, and the Gemara (Zevachim 118b) records an oral tradition that it took an additional seven years to divide all the territory among the shevatim, families and individuals. At the time that the division of Eretz Yisrael was completed, the territory of each shevet was owned exclusively by members of that shevet. Once the division was completed, this hora’as sha’ah no longer applied.

The Gemara (Bava Basra 120a) records a tradition that this hora’as sha’ah applied to all girls who inherited their fathers except for the daughters of Tzelafchad, who were allowed to marry anyone they wanted. Despite their exemption, the Chumash says that bnos Tzelafchad listened to Moshe Rabbeinu and married boys from their own shevet. The Gemara explains that this was a recommendation of Moshe Rabbeinu and not a din. We always recommend that one marry someone with a similar background to their own for practical reasons, since two people with similar backgrounds have a better chance of blending together well and being blessed with shalom bayis.

The Or HaChaim asks: What motivated the chachamim to say that this hora’as sha’ah did not apply to bnos Tzelafchad themselves? The simple reading of the parsha seems to say differently. The problem was raised by the leaders of shevet Menashe because of bnos Tzelafchad; so, what should lead us to believe that this special hora’as sha’ah should apply to all others, but not to them?

The answer can, perhaps, be found in the comment Rashi quotes at the beginning of parshas Mattos from the Sifrei. All other prophets—just like Moshe Rabbeinu—introduce their nevuah with the expression, “‘כה אמר ה—this is the gist of what Hashem said,” but only Moshe Rabbeinu is able to introduce his nevuah with the expression, “‘זה הדבר אשר דבר ה—this is precisely what Hashem has said.” Moshe Rabbeinu was the only Navi who received direct dictation from Hashem, word-for-word and letter-for-letter. All the other neviim were only shown a divine vision and interpreted it using their own vocabulary; even if two neviim were to be shown the same exact vision, each would interpret the vision using his own vocabulary. The Talmud (Sanhedrin 89a), therefore, tells us that it never happened that two neviim were given the exact same prophecy in the exact same words. Sometimes, Moshe Rabbeinu was given direct dictation and, sometimes, he was shown a vision and instructed to interpret it using his own language.

Rav Levi Yitzchak of Berdichev (in Kedushas Levi) explains under what circumstances Moshe Rabbeinu received direct dictation and when—like other neviim—he had to interpret a vision he was shown: whenever Moshe was told something that was only a hora’as sha’ah, he was functioning in the same capacity as other neviim and thus would have to interpret a vision. But whenever Moshe was told a din ledoros, it was not a transmission of nevuah, but rather of Torah, and Torah had to be given via direct dictation.56

It has been accepted for thousands of years that the law prohibiting a girl who inherited land from marrying a boy from a different shevet was a hora’as sha’ah, so why does Moshe Rabbeinu introduce that halacha with the phrase, “’זה הדבר אשר צוה ה—Zeh hadavar?” implies direct dictation, and “tziva” indicates a mitzvah, which is a technical term used only to describe a din which is part of Torah and applies for all generations! Perhaps, this is what led the Gemara to understand the pasuk to indicate that only the din ledoros applied to bnos Tzelafchad and, thus, they were able to marry anyone they chose, i.e., the hora’as sha’ah did not apply to them.

Rabbi Hershel Schachter joined the faculty of Yeshiva University’s Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary in 1967, at the age of 26, the youngest Rosh Yeshiva at RIETS. Since 1971, Rabbi Schachter has been Rosh Kollel in RIETS’ Marcos and Adina Katz Kollel (Institute for Advanced Research in Rabbinics) and also holds the institution’s Nathan and Vivian Fink Distinguished Professorial Chair in Talmud. In addition to his teaching duties, Rabbi Schachter lectures, writes, and serves as a world renowned decisor of Jewish Law.

56 Ed: See also “Mitzvos Ledoros and Hora’os Sha’ah,” above in this volume, Parashas Vayakhel-Pekudei, page 128, where Rav Schachter discusses this distinction as well.