Rabbi Yehuda Amital (whose yahrzeit was last week) was born Yehuda Klein in 1924, in the Transylvanian city of Oradea (Grosswardein). After barely surviving the Shoah he made aliyah, where he became a distinguished Religous Zionist figure. Shortly after his aliyah he changed his name from Klein to Amital. According to Elyashiv Reichner in his biography of Rav Amital (“By Faith Alone,” 2011), “drawing on a biblical verse from Michah 5:6, ‘The remnant of Jacob shall be among the nations, in the midst of many people (amim), like dew (tal) from God, like droplets on grass—which do not look to any man nor place their hope in humans.’” The medieval exegete Rabbi David Kimchi (Radak) explains that the prophet is addressing Israelite refugees who will survive a difficult purge. Radak explains why the prophet allegorized the refugees to dew: Just as dew comes from God, and one who hopes for dew prays to God that it descend, so those refugees will be able to rely solely on God’s salvation.”

Reichner further claims that:

“Yehuda was a bit afraid of the reaction of R’ Isser Zalman Meltzer [his grandfather-in-law] to the hebraization of his name. The fad of hebraizing names was limited mainly to the secular population; it was not received well at all within the haredi community. Yehuda showed Rav Isser Zalman the verses in Michah with the Radak’s comments and told him that the verses made such a profound impression on him that he decided to change his surname. Rav Isser Zalman nodded; he understood the mind of his young grandson-in-law, and accepted his decision.” (p. 147)

I find this paragraph a bit perplexing. Why would he be afraid of hebraizing his name? Many haredi rabbis actually did hebraize their surnames (I have mentioned quite a few in Part I of this series)—no less a personage than the rosh yeshiva of Yeshivat Hevron (Rabbi Amital’s alma mater) was Eastern European-born Rabbi Moshe Hevron; needless to say, Hevroni was not his original surname (that name is mysteriously shrouded in obscurity).

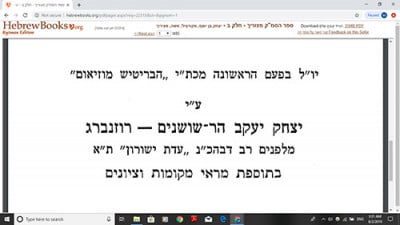

I should point out that just as the hebraization of surnames was a trend, so too has there been a trend in the opposite direction, namely the reversion back to the original surnames. This is a phenomenon that exists in both the secular and religious (mostly haredi) community (each one for different reasons I presume). One example would suffice—one of the most respected litvak rabbis of Bnei Brak is Rabbi Sariel (in itself an atypical haredi given name) Rosenberg, the head of the Bnei Brak court founded by Rabbi Nissim Karelitz (his father-in-law). Rabbi Rosenberg was born in Tel Aviv to Rabbi Yitzchak Yaakov and Tova Leah Har-Shoshanim-Rosenberg. The elder Har-Shoshanim served as the rabbi of a Religious Zionist synagogue in Tel Aviv called Adat Yeshurun. He was also the author of commentary to the medieval French Tosafist work Sefer Mitzvot Katan. Har-Shoshanim is a literal hebraization of the germanic surname (literally, hill of roses). While his father always used both the original surname along with the hebraization (indeed, this is how his name appears on his and his wife’s tombstones), the son chose to revert back to just Rosenberg.

I should also point out that there are several different types of hebraizations; Amital, for instance, has nothing to do with his previous surname, while Har-Shoshanim is a direct translation of a previous surname. There are also other kinds of hebraizations on which I will expand upon in future posts.

(To be continued…)

By Joel S. Davidi Weisberger

Joel S. David Weisberger runs Channeling Jewish History. You can find it on various social media platforms including Facebook and Twitter. He can be reached at yoelswe@gmail.com.