Some books are good; others are timely. Conscripted Slaves is both.

Let me explain: 2014 marks the 70th anniversary of the Holocaust in Hungary. The preferred narrative of that history is well established: Until the German invasion of March 19, 1944, Hungarians Jews lived freely and openly as Jews despite the alliance between Nazi Germany and Hungary. Hungarian Jews were confident–in retrospect all too confident–that the fate of Jews under German occupation elsewhere would not touch them. They were Hungarians and Hungary was different. Yet, within weeks of the German invasion, in April and early May, Jews were ghettoized and by the 15th of May, 437,402 Jews had been deported from Hungary, primarily to Auschwitz–where four out of five were killed upon arrival. What had unfolded in Poland over three years occurred within a matter of days, as 147 trains were sent from the Hungarian countryside carrying an average of 2,975 Jews to their deaths. Nowhere else on the European continent was the pace of murder as intense. By July 8, all that remained of this once vital community were the Jews of Budapest. Enter Raoul Wallenberg.

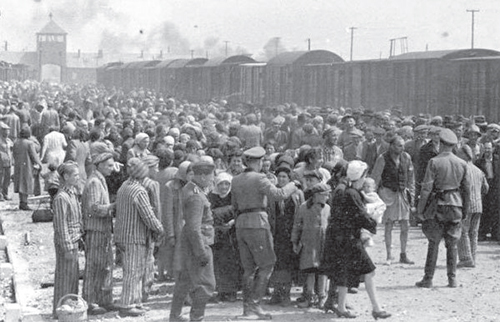

Another way of looking at this massive destruction is to look at the infrastructure that the Nazis built at Birkenau, the death camp of Auschwitz II. Anyone who has been to Birkenau has seen that the railroad track goes through the center of the camp and then splits into three. Few visitors realize that the railroad spur was only built in the winter of 1944 and that the splitting into three was designed for the herculean task of deporting and murdering Hungarian Jews–147 trains, 54 days, 2.7 trains a day. Birkenau could handle three trains a day and for most of that time, it did. The rail spur was essential to implement the Final Solution of Hungarian Jewry.

As the story is recounted in Hungary today, especially with the rise of the right-wing nationalist Jobbik Party that is now part of the government, the Final Solution was imposed on Hungary. Without the German invasion, the treatment of Jews would have been extraordinary. “Our hands did not shed that blood,” so many proclaim in Hungary today. Hungary, they maintain, was an island of decency is the bloodbath of Europe. Not so quick.

The purveyors of this revisionist nationalistic history omit Hungarian participation in the deportation of non-Hungarian Jews to Kamenets-Podolskiy in the summer of 1941, where they were murdered by German Einsaztzgruppen. Anyone who has read Elie Wiesel’s Night recalls the brief description of the reports of these murders when Moche the Beadle, a foreign Jew living in Sighet who was deported, returns to describe what he experienced and the na?ve Jews tragically believe that he has gone mad. He was not alone.

Robert Rozett points out that the shock of these murders among Hungarian officialdom and its Jews mistakenly led Hungarian Jews to believe that the reports of what was happening in Poland and Germany could not happen to them. They did not, they could not internalize, the information that they were hearing, and therefore, they did not take the necessary precautions. Wiesel writes: “It was neither German nor Jew who ruled the ghetto. It was illusion.”

For Rozett, the son of a Hungarian Jewish forced laborer, the subject is personal: at his childhood Seder table when the Maggid began with the traditional words: “We were Slaves in Egypt” they would add would add that our father was a slave in Hungary. One does not forget such a powerful transmission of memory and thus Rozett, the librarian at Yad Vashem, brings his considerable academic skills to explore the history of these conscripted slaves. One must admire his learning: He has mastered the historical documents, the trial records, the memoirs, and the oral histories and thus is able to tell this story both from the perspective of the perpetrators as well as the victims. He contrasts the behavior of the Hungarians with that of the Germans and of the Soviet troops, and is able to demonstrate the link between racial policies and the manner in which Hungarian slave laborers were treated.

For non-Jews, conscripted laborers’ productivity was essential to their survival. Jewish laborers were expendable, if not immediately then ultimately, and the value of their work merely postponed their murder. His understanding is subtle and rather than paint with one brush on a broad canvas, he is able to decipher Hungarian policies toward Jewish slave workers before and after German occupation, and at different times during the war. At first, Germany was perceived as the inevitable winners of World War II and Hungary was expected to continue to reap benefits from its alliance. Later, German defeat was considered inevitable and Hungary was burdened by the choices it had made. Still later, when the Iron Cross took effective control of Hungary, the Hungarians embraced all of Nazi ideology. Rozett is careful to understand that the fate of Jewish slaves differed depending on the larger war picture–real or perceived.

Those of us who are sensitive to telling the story of what the oppressors did to the Jews, can also relate to what the Jews did for themselves: how they dealt with their own fate; the actions they undertook, including escape and going over to the Soviet side. They will appreciate that Rozett devotes almost a third of this book to Jewish responses to their condition and to the impact of the circumstance they faced, the conditions in which they lived, and their sense of self. He also follows the home front. These slaves could, at least for a time, write home and maintain some form of contact with their family. Thus interest in their fate was high and information regarding their situation fragmentary but not inconsiderable.

Contra the preferred narrative of contemporary Hungary, Rozett documents that Jewish slaves often considered their treatment at the hands of the Hungarians worse than their treatment by the Germans. As to escape to the Soviet side, statistics tell a terrible tale. Three of four Jews did not return. He neither omits the precious few who were rescuers, nor the individual Hungarian supervisor who treated his men with decency and respect. There was a choice to be made by perpetrators and bystanders, and desperate Jews remember with gratitude those who remained decent even a half century later.

The most effective way to respond to the rewriting of history is by writing good history, rooted in the sources, grounded in documents, and telling the human story provided by memoirs and oral histories. And Rozett delivers the goods.

By Michael Berenbaum