Part II

Graf Zamoyski Publishes a Charter of Rights for the Local Sephardic Jews

In 1588, Jan Zamoyski publicized his charter of rights for the Jews of Zamocz, which is still extant in the Latin original (in the archives of Krasnystaw) and its Polish translation. The document lays out the provision that the privileges and rights enumerated within only apply to the Spanish and Portuguese Jews and not to the general Jewish population. The Sephardic in the minds of the rights givers are a desirable element that would be a valuable asset to the city and stimulate trade and culture.

Let us now focus on specific excerpts from the charter. In the opening lines of the document Zamoyski informs that “he was asked by one of the Jews of the ‘Spanish Portuguese nation’ to allow him to settle in his city Zamocz in which there has been settled already many people from east and west.” He adds that he consulted with his city council and concluded that in order to increase the population of the city and to develop its commerce, the Spanish Portuguese—both those arriving from Turkey and those with Ottoman citizenship—should be allowed to settle in the city. They can maintain the right to come and go as they please, it is forbidden to persecute them on the basis of their religion and to engage in inquisition, they have the right to keep their traditions and customs and live according to their beliefs. They will enjoy the same rights and privileges as the rest of the underlings of the senators and noblemen. Following is a listing of streets (in the center of the city) in which the Jews can build their house to inherit them to their children, to sell them, or exchange them with whatever they see fit.

In proximity to their residence they are permitted to build a house of worship made of stone. Until such time as the structure is built they are permitted to conduct services and religious services in a private house. They are allowed to have religious tracts for the purpose of prayer and education.

In addition to that, Jews are allowed to gather wood from the surrounding forests as well as stones and mortar for the construction of their homes. In the event that the Jewish population outgrows its present location, they will be allowed to live outside the designated city. Zamoyski also pledged to assign space for a cemetery. The Sephardic Jews are given the right to engage in all kinds of commerce, both in the city and outside of it. Those who are skilled in the art of healing, after taking an examination at the Academy in Zamosc, will be allowed to practice medicine in the city.

They are permitted to wear any type of clothing they like of any color and it is forbidden to force them to wear specific clothing or other features that would identify them as Jews. They are also permitted to carry arms as all other citizens are permitted for self-defense. They are also permitted to build a mikvah as long as it does not hurt the business of the local bathhouse.

Several limitations on commerce were imposed in order not to negatively impact the rights that were given to the Armenians, Greeks and Czechs. Jews were forbidden to trade in liquor, bread and poultry; however, they were permitted to engage in the wine trade. In order not to impact the local merchant guilds, Jews were forbidden from engaging in fur making, shoemaking, butchery and pottery. However, they were allowed to slaughter for their own needs and sell the non-kosher sections at the fairs or in the surrounding towns under the jurisdiction of Zamoyski.

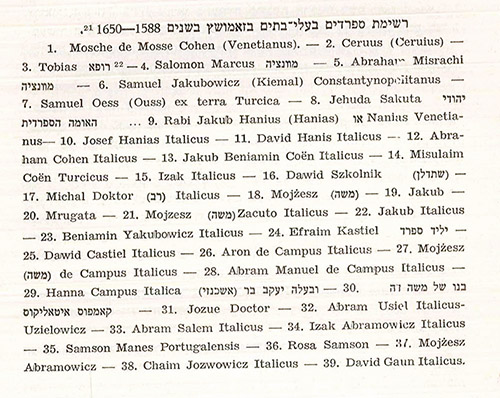

The document also stipulated that the aforementioned Jews should not fall under the jurisdiction of other Jews; they will elect their own leaders and councils in which no Jews of other nations (i.e., Ashkenazim) will be able to participate. No Jew will be accepted in the community without the authorization of the heads of the synagogue. Only with the consent of the majority of the Sephardic congregants will the individual’s name be inscribed in the synagogue’s roster.

The injunction also specified that the Spanish Jews are permitted to elect their own community heads and is granted the jurisdiction to judge their disputes and also mete out punishment against their members if necessary, including excommunication and banishment from the community. Here Zamoyski adds that should a dispute arise between “my townspeople,” i.e., the Sephardim and a non-Jewish resident of the city, Zamoyski himself would adjudicate the case or appoint someone trustworthy and acceptable for all sides.

This remarkable document illustrates the sense of liberalism, an obvious product of the Renaissance of which Zamoyski was heavily influenced by. However, it is important to point out that this sense of liberalism and tolerance did not extend to the local “indigenous” Polish (Ashkenazi) Jews. From a letter dated 1587 by De Mosso Cohen we learn that “the councilor only wants ‘frankim’ to settle there and does not desire the local Jews.” The preference of Sephardim over Ashkenazim continued after Zamoyski’s death when his heir and successor Thomas requested to extend the 1588 injunction for newly arrived Sephardic settlers from Flanders and Holland. This blatant discrimination was based mainly on the economic benefits the city derived from the mercantilist and diplomatic skill and talent of these Jews. In general, these Jews were more cultured and modern and therefore fit in very well in the cosmopolitan atmosphere that the city and its founders fostered.

From the writ in the many injunctions there is also evident the faint hope-on the part of the Polish noblemen- that these Sephardim would prove to be a source of emulation for their “backward” Ashkenazic brethren. This can be observed from the fact that the Sephardim were given the right to accept into their communities Ashkenazim if they so desired and in addition they were permitted to admit local Jews into their educational institutions.

Zamoyski’s vision of creating in Zamosc a center of scholarship and trade never came to fruition. Likewise, his hope that Sephardic Jews would continue to settle there and swell the ranks of the community never occurred either. Schatzky surmises that the Zamocz Sephardim conducted most of their business in nearby Lviv, and never gave the Zamocz community a chance to get off the ground1. According to Schatzky, by 1600 the Sephardic community in Zamocz was no more.

Others contend that the Sephardic community existed there as a separate entity at least until the end of the 16th and possibly even into the first decades of the 17th centuries.

The author is the founding editor at Channeling Jewish History and can be reached at [email protected]. You can also follow him on Twitter under the handle hahistorion.

1 Schatzky, Yakov. Sephardim in Zamosc, Yivo xxxv