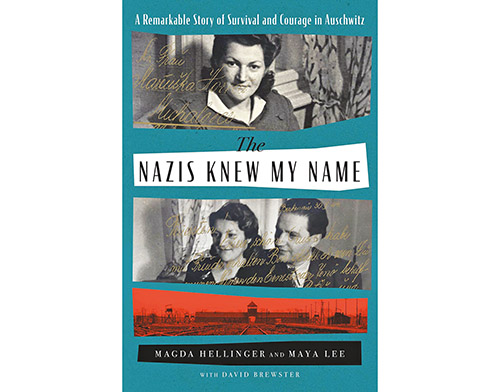

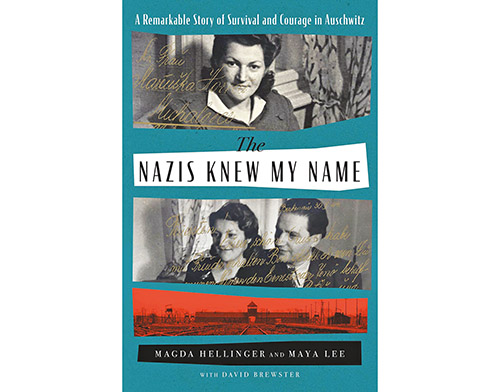

Reviewing: “The Nazis Knew My Name: A Remarkable Story of Survival and Courage in Auschwitz” by Magda Hellinger and Maya Lee. Atria Books. 2022. English. Hardcover. 320 pages. ISBN-13: 978-1982181222.

I was truly blessed to be able to convey the lessons of the Holocaust to public high school students of all backgrounds and nationalities in Queens for 18 years. I remember that as the semester would wind down, I would broach a few “hot” topics briefly. One day, I would challenge the students with the following scenario for comment.

An elderly couple is strolling leisurely along the boardwalk in Miami Beach, Florida, home to many retirees from the northern U.S. and Canada. Suddenly, from the opposite direction, another elderly couple passes. Immediately, there is a visceral physical reaction on the part of the first gentleman who recognizes the second as having been a kapo, a disciplinary overseer, in his lager, concentration camp, during the Holocaust. The first gentleman averts his eyes in disgust and with genuine hatred shouts, “You should be put on trial for war crimes instead of strolling freely!” Needless to say, the two spouses and all the onlookers were horrified.

I posed this question to the class: “What would have been your reaction to meeting a Jew who had served as a kapo in your concentration camp?” Truthfully, I knew this was an impossible question for them to even consider, as it was for me as well. I just raised it to engender some serious thoughts and consideration.

It is many years and many careers later, and I believe that I just came across an answer to this difficult question as a result of reading “The Nazis Knew My Name.” The memoir, published in 2021 by Simon and Schuster, is drawn from Magda Hellinger’s personal account and was completed by her daughter Maya Lee’s extensive research. At age 25, Magda Hellinger was deported from her town in Slovakia on the first transport from the area to be sent to the Auschwitz concentration camp.

Separated from her parents and siblings, Hellinger was on her own in her battle to survive. A kindergarten teacher by profession, she soon stood out for her gentleness yet authority, and was selected by the SS to serve in roles of leadership. The SS, in their cruel, twisted way of thinking, figured out that if they put Jewish prisoners in leadership positions over their fellow prisoners, they would deflect hostile attention away from themselves. And so hundreds of prisoners in the many killing and labor camps throughout Poland were overseen by fellow Jews who were put in the “no-win” situation of disciplining their fellow prisoners or being disposed of themselves.

Hellinger proved time and time again that she could display authority while still showing compassion to the women prisoners in her charge. Throughout her three plus years in the camps, she held different positions, being transferred where the Nazis saw her abilities to be best utilized. She served as the Blockalteste of hundreds of women in the notorious Experimental Block 10 in Auschwitz proper and then as the Lageralteste of 30,00 women in Camp C in Birkenau. At one point she was put in charge of a block of French intellectual women to whom the Nazis believed she could relate and command respect. In each position, Hellinger walked a dangerous line, using her role to save lives while avoiding being seen as too lenient on her charges and risking execution for them and herself.

Wherever she was faced with a particularly painful, confusing situation in which she had to choose between following the Nazi line or deviating in some way to save the lives of her inmates, she would recall the message which her mother ob”m had conveyed to her as the family was being marched to the railway station after being rounded up in their town. Holding her daughter’s head between her hands, she sobbed, “My dear daughter, I must tell you something. I don’t think you remember this but when you were a little girl of 8, your father took you to the famous Belzer Rebbe. He put his hands on your head to bless you and said, ‘This girl has a special mission in her life. She is going to save hundreds and hundreds of Jewish souls.’ Remember this! Remember this!”

Her compassion and quick thinking saved her prisoners from certain death by volunteering them for work in factories as opposed to being exposed to the brutal elements in outside work, sending them to kitchen jobs where they could secure a bit more food for survival, and even preventing them from joining what seemed to them as better situations when in fact they were headed for the gas chambers which only Hellinger was privy to.

After liberation, former prisoners who had been overseen by Hellinger would run up to her and hug her for inspiring them to hold on and survive. Ironically, there were others, even cousins and other relatives, who still resented the “slap across the face” that Hellinger inflicted upon them to prevent them from making a choice that would have cost them their lives. From these accounts, I was able to answer my own question to my students so many years ago as to what the correct attitude should be to kapos and other Jewish assistants to the Nazis who were made to oversee their brethren. The answer lies in their purpose in carrying out this role. If they were only concerned for their own survival, they might have taken the power of their positions too far and inflicted unnecessary pain on their fellow prisoners. But if they were accorded the role of “savior of her people” as Hellinger was through the bracha of the Belzer Rebbe, then their motivation was pure and they should be honored and respected for their courage and compassion.

Every Holocaust memoir has a singularly uplifting message to convey. “The Nazis Knew My Name” is no exception.