Rabbi Mordechai (Mottel) Kanelsky and his wife, Shterney, are well-known and highly respected figures on the New Jersey Jewish scene. They have resided in Hillside for the past 37 years, during which time they have spearheaded the Lubavitch Bris Avrohom Organization that is housed in their shul, Congregation Shomrei Torah/Ohel Yosef Yitzchok. In addition, Rebbetzin Kanelsky oversees a recently refurbished luxurious women’s mikvah used by women in communities as far-flung as Atlantic City, Seagate and even Williamsburg, in addition to local communities.

The underlying story of their unremitting and tireless commitment to Am Yisrael began almost six decades ago in the Soviet Union, when being Jewish was a criminal offense punishable by imprisonment or worse. That is the reason why their recent trip back to Russia, in December 2018, after almost 50 years was a milestone event in their lives they never imagined would take place.

Chief Rabbi of Russia Berel Lazar, as well as Rabbi Kanelsky’s brother Rabbi Meir Simcha Kanelsky, who serves as a Lubavitcher shliach in Moscow, had been urging the Kanelskys to visit Russia for many years, to no avail. “Honestly, I was afraid that the KGB would arrest me and I would never again see the light of day,” admitted Rabbi Kanelsky. Rebbetzin Kanelsky was equally hesitant, as her memories of painful anti-Jewish events were still vivid. But in recent years, the Kanelskys got to know the shluchim, emissaries, from Russia through their visits to the Rebbe and even to Hillside to visit the headquarters of Bris Avrohom. Finally, after 49 years, the Kanelskys conceded. Their mission in Russia was to provide needed chizuk, support and strength to the local Jews whose Jewish lives are so much freer and richer than theirs had been.

During the course of their six-day whirlwind trip the Kanelskys addressed over 17 groups between them. Rabbi Kanelsky addressed groups of young yeshiva boys as well as avreichim, young men, and seniors. Rebbetzin Kanelsky addressed groups of girls and women who are all interested in enhancing their Jewish practice. Together they addressed a large group of orphaned and disadvantaged Jewish youth.The climactic presentation of the trip came on the evening of the 19th of Kislev, referred to as the New Year of Chassidus, marking the chag ha’geula, release from prison, of the Alter Rebbe. In all of their speaking venues, the Kanelskys regaled the audiences with the courageous stories of the mesiras nefesh, total devotion, of their parents and in-laws to the Jewish education of their children and thus the perpetuation of Yiddishkeit within their families.

Upon arrival in Moscow, the Kanelskys met with Chief Rabbi Lazar, who greeted them warmly and thanked them for agreeing to come. Then off to Malachovska, a suburb of Moscow, where Rabbi Kanelsky had spent his youth in close proximity to the home of his grandparents, which had been a hub of warmth and hospitality to all those who dared openly disclose their Jewishness. Rabbi Kanelsky’s memories flooded back to his father’s dilemma, which he pondered daily on his half-hour walks to work. How was he to provide a Jewish education to his son under the noses of the Communists and how could he possibly pay for a melamed, a teacher, to risk his life and come and teach the boy? Then it was off to the Yeshiva Ketana Tomchei Temimim, where Rabbi Kanelsky told the students of his father’s hiring of a very special melamed, Rabbi Berel Rickman, who had learned b’chavrusa, in partnership, with the Rebbe in the town of Nikalayov, and who sported a long beard, an act of daring and courage in those days. Rav Rickman taught little Mottel from the ages of 5 to 8 and introduced him to the concept of the Lubavitcher Rebbe.

The Friday-night meal was shared with over 70 sincere Russian men and women of all ages who have taken upon themselves the full complement of Jewish observance. Rebbetzin Kanelsky inspired them with her family’s story of mesiras nefesh. Living in Samarkand, the Zaltzmans were part of a small group of committed Jews. Parents of four daughters as well as two sons, they had a great dilemma with which to grapple. How could they send their daughters to public schools that preached communist ideology, the denial of religion and, worst of all, would force them to attend school on Shabbos? They could counter the teachings of the school with their strong beliefs at home, but how could they get around Shabbos attendance? They brilliantly decided to send each girl to a different school. Every Monday when the girls returned to school, they each had a different excuse note, once claiming a headache, then a toothache, then a virus. They were able to get away with this ruse for a few years as their mother was a gifted seamstress and would make lovely garments for the teachers in charge. Thus the girls were able to keep Shabbos properly. But the constant dodging of the authorities placed a heavy emotional strain upon the entire family.

One Shabbos morning, Rebbetzin Kanelsky was to experience nothing less than a “miracle” on her way to shul. When she approached what she assumed was an electrified fence leading to the courtyard of the shul, she confronted two Russian guards. When they saw the concerned expression on her face, they immediately assured her that being Shabbos, the fence would not be electrified and was fine to walk through. “I could not believe that Russian guards would understand the concept of Shabbos and its meaning to a Jewish woman!”

On Sunday, the Kanelskys addressed the 150 women of J-Club, some of whom had visited Hillside. After an emotional address by Rebbetzin Kanelsky followed by a lively program of chassidic songs, the women assembled were asked to take upon themselves an additional mitzvah. One of the young women vowed to provide her infant son with a bris milah, circumcision, despite the vehement objections of her non-Jewish husband. The raffle ticket offering a free trip to “770,” Lubavitch Headquarters in Brooklyn, was awarded to a young woman who had danced the evening away in enthusiastic devotion to her newly-found Yiddishkeit.

Following the address to the young women, the Kanelskys joined Rabbi Kanelsky’s brother at a kosher restaurant above the shul. The Kanelskys feel that what happened next was a clear occurrence of hashgacha pratis, God’s intercession on their behalf. During their meal, they met a woman who had visited Bris Avrohom in New Jersey and had been very impressed with their accomplishments. When she shared that her husband was an official of the town of Malachovska, the Kanelskys immediately told her of their great disappointment at not being able to visit their grandparents’ home. She quickly contacted her husband who reached out to the owner, who was brought back to open the home.

It was inside their mutual zaidy’s home that the floodgates of memory opened up for the rabbi and rebbetzin. Rabbi Kanelsky emotionally peered down into the cellar where he had spent the most traumatic two years of his young life. The story goes that after three years of learning with a private melamed, little Mottel would have to be signed up for school. For boys, the situation was even worse than for the girls as they would not be allowed to wear caps or tzitzis in public school, in addition to being forced to attend on Shabbos. Mottel’s father presented him with an almost “choiceless choice” for a little boy of only 8. He could suffer the indignities of public school and chilul, desecration of, Shabbos, or he could go underground to learn Torah and not emerge until they hopefully were allowed to leave Russia. The little boy chose the latter and his two years of isolation underground began. During those long and seemingly unending years, Mottel had no childhood, no friends, no freedom, just long hours learning with his melamed with no clear end in sight. One particularly traumatic day occurred when the school officials came looking for him and he escaped them by following his bubbie’s instructions in Yiddish to run from room to room to evade them. It was during these years that Mottel’s father decided to grow a beard, a bold and daring act, to set an example of mesiras nefesh to his young son.

Rebbetzin Kanelsky shared her family’s stories of mesiras nefesh with other women’s gatherings. She shared how her parents, at great risk to themselves, took 15 local Jewish boys from Samarkand into a back building on their property and brought in two melamdim to teach them for two and a half years. During the entire period, the Zaltzman family cared for them as if they were their own sons, providing them with food, lodging and emotional support. Needless to say, it was an extraordinary act of courage which, sadly, engendered fear in all involved. Rebbetzin Kanelsky attested to never eating pas akum, bread baked by a gentile, and chalav stam, milk not properly supervised, even during the precarious 10½ years that they lived as refuseniks.

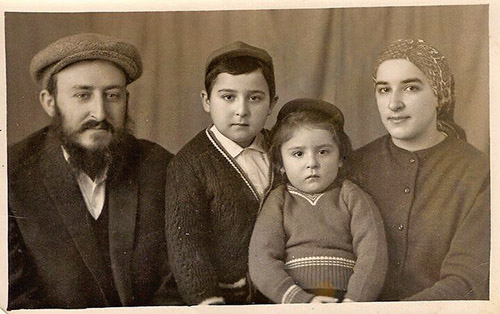

At the keynote address in front of hundreds of assembled in the grand ballroom of a Moscow hotel, Rabbi Kanelsky drew the precarious story of his family’s survival in communist Russia to its moving finale with the story of the Rebbe’s intervention. In 1968, the family appealed to the emigration authorities for permission to leave Russia. The clerk at the office tore up the family’s papers and pronounced that they would never be granted permission to leave but would die in Russia. Rabbi Kanelsky’s father was distraught, but he came up with a plan. He took a photograph of his family and sent it to a cousin in Crown Heights to present to the Rebbe with the caption: “We want to come to visit our zaidy.” The cousin delivered the picture to the Rebbe, who did not respond but simply placed the photograph in his drawer. Fast forward 18 months, and the family was suddenly sent exit papers and told to pay a certain sum and be gone in eight days. In less than eight days they managed to leave Russia and travel through Vienna to Israel.

One year after settling in Nachlas Har Chabad outside of Kiryat Malachi, the family managed to scrounge out enough money for two tickets to visit the Rebbe in New York. It was during that momentous meeting that it became clear to father and son that the Rebbe had indeed intervened and arranged for their permits to leave Russia. Just as reported by their cousin, the Rebbe had placed their family picture in his drawer without comment. But on Erev Yom Kippur of the following year, he summoned the cousin back to his office and returned the photograph, saying that he did not need it any longer. This gesture caused great disappointment to the cousin, who conveyed it to the family in Russia. But within four months, during the Hebrew month of Shevat, the Kanelskys received their exit papers. The story became clear. To this day, the visit to the Rebbe after the family’s release was one of the most precious experiences of Rabbi Kanelsky’s life. It was at this meeting that the Rebbe taught little Mottel the true meaning of tzitzis. The Rebbe pointed out to the young boy who was sporting his tzitzis proudly that the numerical product of the four corners and the eight strings on each corner equaled 32, the gematria, numerical value, of lev, heart. The message that the Rebbe conveyed to the young Mottel that day was that when one wears tzitzis, “he has a good heart, a Jewish heart and a chasidishe heart and Hashem will always be there to provide you with all three.”

At the conclusion of his powerful remarks, Rabbi Kanelsky “shook up” the crowd by re-phrasing the well-known verse from the Haggadah, “And if the Rebbe had not taken us out of Russia, we and our children and children’s children would still be enslaved to Russia.”

After their marriage in 1981, Rabbi and Rebbetzin Kanelsky made it their life’s mission to help repay the Rebbe for saving their families from obliteration by the communist regime and helping them establish model Jewish homes in Israel and America. To this day, every project they undertake of behalf of klal Yisrael is a tribute to the Rebbe and his teachings. Most definitely, this includes their jubilee “chizuk” trip back to Russia, during which they impacted so many Yiddishe neshamos.

To learn more about the projects of the Kanelskys and Bris Avrohom, visit www.brisavrohom� or call 908-289-0770.

By Pearl Markovitz

�