Madison, NJ—Since the end of World War II, the phrase “never again” has been uttered countless times. On the surface, its meaning seems straightforward—never again should people allow atrocities such as those perpetrated during the Holocaust to occur. This mass genocide of millions of people represented one of the darkest periods in modern times. Not merely mass genocide but, in many instances, medically sanctioned genocide.

Stacy Perlstein Gallin, DMH, Drew University Adjunct Assistant Professor, Program Creator and Conference Chair, said, “The Holocaust is a unique example of medically sanctioned genocide. Studying the ways in which the medical profession actively participated in the labeling, persecution, and eventual mass murder of millions of individuals deemed ‘unfit’ during World War II is essential because of its relevance for modern medicine, bioethics, health care policy, and human rights endeavors. We must reflect upon the past in order to protect the future.”

In further examining the bioethical questions inherent in the concept of medically sanctioned genocide, historians, bioethicists, and the medical and scientific communities seek to understand not just what happened, but how it was able to happen. Only by understanding how those sworn to “do no harm” ultimately became ruthless murderers can the perpetuation of “righteous medicine” occur.

On Yom HaShoah, the Medical Humanities Department of the Caspersen School of Graduate Studies at Drew University, in conjunction with the Center for Holocaust/Genocide Study, presented a full-day conference entitled “Medicine, Bioethics, and the Holocaust.” Organized by Phil Scibilia, DMH, Chair of the Medical Humanities department at Drew, and Gallin, the intended purpose of this conference was to explore the ethical transgressions and perversions of established medical practices that occurred prior to and during the Holocaust, in order to better understand how these horrors were allowed to occur and to help protect against them ever occurring again.

Conference presenters spoke in an order designed to walk attendees through the history of medical and ethical practices common in Germany during the years leading up to WWII, painting a clear picture of how the prevailing attitudes and behaviors of the time seamlessly led to the Holocaust. Robert Ready, PhD, Dean of Drew’s Caspersen School of Graduate Studies, provided the opening remarks, followed by Dr. Tessa Chelouche of Israel’s Technion Institute, and author of a “Casebook on Bioethics and the Holocaust.” Chelouche explained that the Nazis did not create the concept of killing those deemed “unfit”—that practice began years before the Final Solution, by mainstream German physicians and government officials. She explained how 400,000 non-Jewish German citizens were sterilized against their will prior to the Holocaust merely because they were deemed “unhealthy” and therefore not fit for reproduction. At that time, abortions were illegal for healthy Aryans, but were forced on others for eugenic reasons. These practices were considered to benefit public health and therefore were perfectly acceptable by medical standards.

The idea of “life not worthy of life” became a mantra, and those deemed a burden to society—whether financial or genetic—were systematically eliminated. In 1939, the German Reich circulated a decree requiring physicians to report children under the age of 3 (and ultimately up to the age of 17) who showed signs of severe disability. These children were sent to specially designed children’s killing centers where they received lethal overdoses of sedatives—all in the name of preserving society.

The start of WWII led to Germany’s state-sanctioned “euthanasia program,” where physicians were permitted to “relieve people of their suffering.” The killing of the “mentally dead” (psychiatric patients) became commonplace, first in gas chambers and crematoria and later through the use of lethal injections. By the end of the war, over 200,000 Germans—not Jews—were murdered as a result of this program. By calling these murders “mercy killings,” Germany was able to maintain the appearance of propriety and compassion.

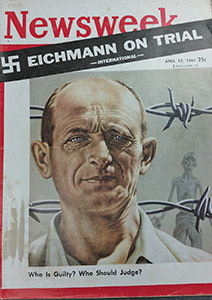

Falsification of medical records and attempts at secrecy by the German government failed and eventually politicians, fearful of backlash, officially halted the practice in 1941. Adolph Hitler himself clearly understood that world opinion would go against Germany if word of the killing program got out, yet he justified the Final Solution as eliminating a significant health threat to Germany.

Interestingly, the teaching of medical ethics was compulsory in German medical schools at that time, and Germany was the first country with an official guideline for human research. Students were taught about eugenics, euthanasia, and the concept of sacrificing the few for the good of the many. The perversion of these lessons “was genetic engineering and social Darwinism taken to the extreme,” said Michael Berenbaum, PhD, director of the Sigi Ziering Institute, professor of Jewish studies at American Jewish University in Los Angeles, and author and editor of 20 books. This eventually led to the Final Solution and the medical experiments performed in concentration camps, all in the name of public health and established medical practice.

Today, people cringe at the thought of these actions. How could Germany have justified murder and called it medicine? Patricia Heberer-Rice, PhD, a historian with the Mandel Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, explained that it became a simple extension of “life unworthy of life,” which led to the murder of people considered no longer useful, such as geriatric patients, and ultimately to the genocide committed in the name of preserving a “healthy” Germany during the Holocaust. Nazi doctors during the Nuremberg trials never apologized for their actions, repeatedly using moral defenses rooted in the legalities and teachings of that time.

Under the guise of promoting German health, state sanctioned murder became the norm. How simple, then, for Hitler to initiate the Final Solution, which called for extermination of those viewed as a “cancer on society.” As Berenbaum explained, “with ‘life unworthy of life’ the medical community had a choice regarding treatment, but there is only one treatment for cancer.”

Berenbaum spoke of frightening comparisons between the original euthanasia program and the eventual genocide that we know as the Holocaust. Nazi gas chambers and crematoria were modeled after those used originally in Germany. The six concentration camps were modeled after the original six killing centers. The Nazi transport of Jews to the camps was foreshadowed by the transport of the handicapped to the killing centers. Sterilization and medical experimentation by Nazi doctors evolved from legally sanctioned forced sterilization and experimentation in Germany before the war. The Holocaust itself—mass murder in the name of preserving a pure Aryan nation—evolved from those original killings in the name of preserving a “healthy” Germany.

The German medical community not only allowed this to happen, but actively participated in the perpetuation of medically sanctioned genocide. “First, do no harm,” the basic tenet of physicians, was irrevocably altered by these horrific actions yet, in their view, Nazi doctors were adhering to their oath. Peter Nelson, MA, director of the New York Office of Facing History and Ourselves, explained, “The Nazi physicians believed in healing the body but, in this case, the ‘body’ was Germany. Like a gangrenous leg, a portion of the body [Jews, gypsies, and others] needed to be excised to save the entirety of the body.”

“We all say ‘never again,’ but that means never again in the 40s will the Nazis exterminate Jews. What are we doing to ensure the broader meaning of ‘never again’? That requires education, not just in medical schools, but beginning in middle school, high school, and college,” continued Nelson.

Presenters and audience members discussed current issues like DNR orders and quality-of-life issues, likening them to the early stages of the Final Solution, and agreeing that education is the only way to safeguard the future. One audience member commented that “this is all wonderful, but there needs to be follow up; there needs to be more done; there needs to be continuing education.”

Chelouche agreed, saying, “We all need to learn from this because it brings up issues relevant to doctors today. Doctors need to remember that they hold the power of life and death in their hands and that, given the right circumstances, we are all prone to cruelty, capable of blindly following a powerful evil.” She emphasized that “medicine can be a dangerous profession if we so choose. We need more than just codes to be kept in line. Codes are not laws. There needs to be ongoing programs for healthcare professionals, especially medical students, on all levels.”

Heberer-Rice commented, “The Holocaust Museum has always focused on the survivors first but is now also focusing its efforts on education. All medical schools should regularly incorporate medical ethics in their curricula.”

While all were in agreement that education rooted in history is vital to safeguarding the future, and that medical ethics is a necessary component of that education, some cautioned against always using the Holocaust as a benchmark. “We must not use the Holocaust in a way so as to end discussions, it must be used to promote discussion,” stated Allen Keller, MD, Associate Professor of Medicine at NYU School of Medicine, Director of the Bellevue/NYU Program for Survivors of Torture, and Director of the NYU School of Medicine Center for Health and Human Rights.

Open discussion and analysis of case studies, combined with medical ethics training, is the best way for future generations to understand the relevance of the Holocaust to their lives. Berenbaum said “it cannot be said that the past has nothing in common with our world today. It is important for this to be taught and remembered, especially the implications for the medical profession.”

To help promote education and begin this vital dialogue, the afternoon sessions included a discussion panel, where participants debated “The Lasting Legacy of the Holocaust for Medicine, Ethics, Health Policy, and Human Rights Endeavors,” followed by workshops dedicated to brainstorming ideas for integrating the lessons of Nazi medicine into current education and/or outreach. Conference attendees were encouraged to share ideas and bring them back to their respective medical, academic, and general communities. The day concluded with the keynote speech given by Arthur L. Caplan, PhD, Drs. William F. and Virginia Connolly Mitty Professor and founding head of the Division of Bioethics at NYU Langone Medical Center in New York City, co-founder and Dean of Research of the NYU Sports and Society Program, and head of the ethics program in the Global Institute for Public Health at NYU. Caplan is widely considered to be one of the premier bioethicists in the world, and the founding father of the academic field of Holocaust Studies and Bioethics. His speech was entitled “Euthanasia in Germany, Assisted Dying in Europe and the US Today—What Are the Lessons From the Past?” and summed up the day’s presentations by further outlining how we must learn from the mistakes made prior to and during the Holocaust, and continue to educate those in positions of power and influence to ensure these mistakes are never replicated.

Attendees at the conference ranged from high school students to rabbis, medical professionals, interested community members, and Holocaust survivors like speaker Ernie Wolf of Rutherford, NJ. All agreed on the vital importance of the lessons learned, not just in terms of remembering the past, but in protecting our future. Said Rabbi Yaakov Mintz, faculty member at Rae Kushner Yeshiva High School in Livingston, who brought his Torah and Science class to the conference, “Most valuable to our students was sensing the passion and seriousness in the room as the presenters discussed and debated their views on applying the lessons of the Holocaust to contemporary bioethics. Exposure to people with the mixture of expertise and idealism as those presenting at this conference will hopefully give our students a real taste of how vital the lessons of the Holocaust can be in our modern society.”

Joey Kirsch, senior at RKYHS and a member of Rabbi Mintz’s class, commented, “We learned that it is important to teach these lessons to make sure it never happens again. Medical students have to be taught to be human before they are taught to be doctors. That’s something I never thought of before.”

Other attendees applied the relevance of the conference to lessons beyond the confines of stereotypical Holocaust education. Said Heather Ellis Cucolo, adjunct professor at New York Law School, and director of the Mental Disability Law Program, “The conference not only teaches us about the horrific events of the past but instructs us on the dangers of genocide and prejudice that exist today. As Professor Michael L. Perlin [professor of Law Emeritus at New York Law School] astutely notes, ‘it appears painfully clear that, while the worst excesses of the past have mostly disappeared, the problem is not limited to the pages of history.’ For persons suffering from a mental disability, unconscionable crimes of torture, confinement, and degradation continue to support the desperate need for the enforcement of international human rights, protection against political abuse, and medical and psychiatric mistreatment. Therefore, I am grateful to Dr. Gallin and other contributors who continue to encourage academic think tanks on how to prevent continued crimes against humanity.”

The conference ended with Scibilia announcing—to thunderous cheers and applause—the launch of a concentration and certificate program on Medicine, Bioethics, and the Holocaust within the Medical Humanities Program at Drew. It is Scibilia and Gallin’s hope that the conference will serve as the foundation of a larger program intended to ensure that the ethical abrogation of the medical community during WWII will never be repeated.

That the Holocaust occurred at all is terrifying. That we must keep it from happening again is paramount. The only way to accomplish this is through education, for only by understanding the past can we preserve our future. “Never again.”

By Jill Kirsch