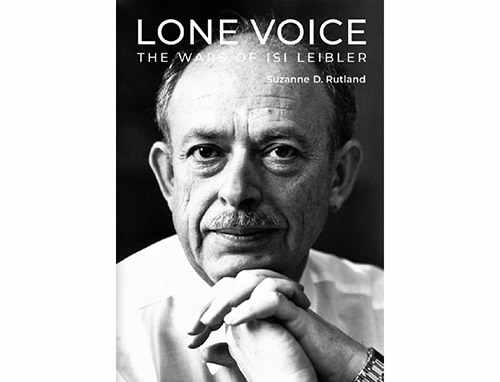

Reviewing: ‘Lone Voice: The Wars of Isi Leibler’ by Suzanne Rutland. Gefen Publishing House. 2021. English. Hardcover. 680 pages. ISBN-13: 978-9657023228.

Editor’s note: Isi Leibler passed away earlier this month. We are pleased to present this review of a work that celebrates his unique personal and cultural impact on Medinat Yisrael.

Communal leaders who take on establishment bodies and challenge accepted wisdom are not the norm. Leadership is no route to a quiet life and can all too easily impact personal relationships. Accommodation comes more easily than confrontation to many who have climbed the greasy pole of politics, and communal politics are no exception. But Isi Leibler, z”l, was no ordinary leader. His career and record mark him out as an exceptionally resourceful fighter for Jewish rights.

Leibler’s turbulent life is chronicled in this work by Australian Jewish historian Suzanne Rutland. It portrays him as a lone voice at times, and he certainly had no shortage of battles, most of which he chose to enter. Drawing on his extensive archive and with material from countless interviews and contemporary sources, Rutland has given us a substantial picture of Leibler’s life and “wars.” At 642 pages it is largely uncritical, yet very readable; but it is not a short read. Rather than be deterred by its length, one can skip the detail. For other readers, it is the detail that supplies veracity and colour.

Born in 1934 in Antwerp, Leibler reached a safe haven in Australia with his family just three months before the outbreak of World War II. Australia was something of a Jewish outpost as he grew up, but the establishment of the Jewish State in 1948 while he was in his bar mitzvah year marked him for life.

Leibler was brought up within a religious Zionist family and never wavered from that path. From an early age he was a communal activist. He saw, far earlier than most, that the significant Jewish community in Soviet Russia was in a desperate plight that demanded international attention.

As early as 1959 Leibler began campaigning for Soviet Jews, working with a small international network. It was not well known at the time that Israel ran a clandestine operation—reporting directly to the prime minister—to help beleaguered Soviet Jewry. Members of the group cannily identified Leibler as an effective mover and shaker, even though he was still in his 20s.

Leibler began a press and lobbying campaign that resulted in Australia becoming the first country to raise the plight of Soviet Jewry as a human rights issue in parliament and subsequently at the United Nations.

Years were to pass before campaigns like Leibler’s would be emulated to any degree by major Jewish communities in the United States and Great Britain. This was no small achievement for Leibler, not least as he was operating from the far smaller and more geographically distant community of Australia.

In a sad comment on communal politics, the prominence of the Soviet Jewry campaign caused deep resentment within the executive council of Australian Jewry, which felt its authority to speak for the community had been undermined. However, a far more significant issue of principle arose with none other than the legendary Nahum Goldmann, one of the founders of the World Jewish Congress and its controlling figure from 1948 until 1977.

Goldmann was in effect world Jewry’s foreign minister (if not president). He is rightly credited with leading the negotiations with West Germany that led to German reparations to Jewish individuals and Israel. On Soviet Jewry Goldmann’s policy was of quiet diplomacy behind the scenes. It was the antithesis of Leibler’s robust and loud approach.

By the mid-1960s Leibler’s campaign had made him a player on the international Jewish stage, and a clash with Goldmann was inevitable. When it came, Goldmann’s approach did not have the support of the Israeli government or many leading campaigners.

At the age of 30, Leibler was not deterred from pressing his case. His rejection of the traditional Jewish approach of quiet diplomacy behind the scenes was to remain a theme of his life for the next 50 years.

Leibler remained a frontline campaigner for Soviet Jewry throughout the next 20 years, when the campaign formed a major preoccupation for Jewish individuals and communities. It inspired generations of young Jews like me to throw everything they could into active involvement under the motivating banner of Let My People Go. Risking my degree and the ire of my parents and tutors, I took part in the second World Conference on Soviet Jewry in Brussels in 1976, where Leibler was, to me, an iconic figure.

In his business life he was building Jetset Tours into the largest retail travel organization in the Southern Hemisphere. He was formidable and influential in political life in Australia. He battled for Israel and against antisemitism, and often against communal opponents, all charted in detail in the book. He rose to be president of the Executive Council for Australian Jewry in 1978-1980; again in 1982-1985; for a third term in 1987-1989; and a final term in 1992-1995.

Leibler enjoyed a long friendship with Bob Hawke, Australia’s prime minister, from 1983 to 1991. Until Hawke turned against Israel, he was a philo-Semite who was utterly committed to the welfare of Soviet Jews. As the preeminent leader of Australian Jewry, the part played by Leibler cannot be understated.

Leibler’s role in achieving the freedom of Soviet Jews to emigrate to Israel, and equally to live as Jews in the USSR, was nothing less than titanic. It is impossible to do justice to it in a book review, but reading this work will convey more than a flavor of Leibler’s leadership, strength of purpose and drive during the long years of campaigning at home and abroad.

The battle for Soviet Jews’ freedom was not fully won until the early 1990s, but Leibler was able to see the impossible dream that he had harbored since the 1960s come to reality. Perhaps no single individual contributed more to a stunning victory that changed the Jewish world.

In 1998 Leibler and his wife, Naomi, made aliyah, residing in Jerusalem. The disposal of his business interests in Australia allowed time to focus on major preoccupations including life and politics in Israel, diaspora-Israel relations and combatting assimilation. It also brought him back into active involvement with the World Jewish Congress, the umbrella body for national Jewish communities.

Today’s WJC, whose president is Ronald Lauder, has a skilled professional leadership that steers its affairs, including its decision-making and finances, with openness and transparency. That was not the case in 2000. The WJC’s top professional was Israel Singer, who enjoyed the patronage of then-president Edgar Bronfman. In Leibler’s perception, the Bronfman-Singer relationship was too close to be healthy and the WJC’s governance had been reduced to something akin to a personal fiefdom among the two and their coterie.

Leibler sensed a need for greater financial transparency. In time it emerged that Singer had plenty to hide. There were financial skeletons in the closet. The unravelling of the sorry chapter in the WJC’s history is revealed in one of the most compelling chapters in the book.

If Bronfman-Singer thought they could intimidate Leibler, they had chosen the wrong opponent. Audits could not account for millions of dollars of WJC money, and one unsavory revelation followed another. Despite enormous pressure—and not much support from world Jewish communities other than Australia—Leibler stuck to his guns.

Eventually the WJC backed down when it became impossible to conceal that it was mired in scandal. Singer had charged the WJC for expenses and consultancy fees of hundreds of thousands of dollars in addition to his salary. He stood accused of misappropriation of funds on a huge scale. Finally, in March 2007, Bronfman fired him. Later Bronfman acknowledged that he had been betrayed by Singer, who “helped himself to cash from the WJC office, my cash.” Singer has largely disappeared from public Jewish life and keeps a low profile. A full accounting of the money that came into his hands has never been established.

In June 2007 Bronfman stepped down and Ronald Lauder succeeded him as president of the World Jewish Congress. Lauder and his team have restored the reputation of the WJC, which is now in a very different place. Leibler can take the credit for rescuing it.

One further battle has to be related.

The Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany administers German reparations money. The annual sums are many millions of dollars, paid to survivors and heirs around the world. Leibler wrote a “Candidly Speaking” column in the Jerusalem Post beginning in 2007. Questions were asked about the transparency of the decision-making and finances of the Claims Conference. Leibler wrote a series of trenchant pieces on the subject. The Claims Conference had a tin ear for any questioning of its actions and seemed to believe that attack is the best form of defense.

When Leibler wrote articles lambasting the Board of Deputies for what he thought was timidity and misplaced quiet diplomacy, I took issue with him and demonstrated that he had been misinformed. He courteously listened to my responses and was big enough to accept that he did not have all the information needed to make a judgment. Out of our initial tense exchanges a friendship grew.

The strong leadership that Isi Leibler brought to communal and international Jewish life deserves respect and admiration. This book stands as a comprehensive record of the life and battles of a central participant in modern Jewish history.

“Lone Voice, The Wars of Isi Leibler,” by Suzanne Rutland, is published by Gefen Books.

Jonathan Arkush was president of the Board of Deputies of British Jews from 2015 to 2018.