Last month, we visited Bethel, New York, home of the infamous Woodstock Festival; the iconic event in modern American history, which drew over 400,000 attendees. In 2017, the site was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It has been fifty years since the “three-day festival of peace and music” took place in August 1969. My thoughts turned to the parsha of that week, Balak, and a negative connection popped into my head. This “counter-culture” musical gathering had a proliferation of illegal drugs, sex and immodesty. The immorality of Balam, whose directive it was to curse the Jews, seemed analogous to the immorality of this enormous assembly of carefree hippies. I don’t know why I was so judgmental at first glance. What happened to judging people for good, dan l’kaf zechus? Don’t all people deserve the benefit of the doubt?

A second thought occurred to me. Wasn’t it a Jewish man who hosted this historic gathering on his 600-acre dairy farm? I decided to ditch the immorality approach for the Bethel anniversary and focus on a story of chesed and other Jewish values, such as advocacy on behalf of others who are less fortunate.

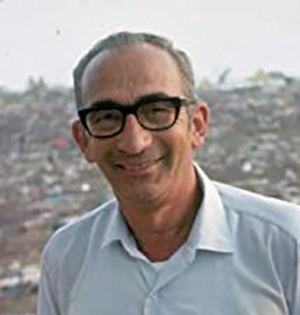

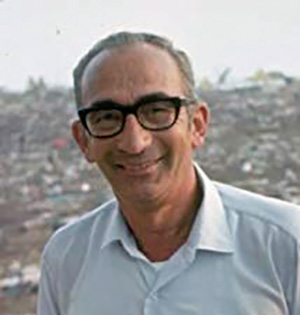

Two other towns (Saugerties and Wallkill) rejected the peace and music festival before Max Yasgur, z”l, and his wife Miriam decided to host it in Bethel on their homestead. Yasgur was the son of Russian Jewish immigrants, Samuel and Bella Yasgur, who emigrated to the U.S. from Minsk. In the 1960s, they were the largest milk producer in Sullivan County, New York. Here is Yasgur’s message to the Bethel Town Board when it was hesitant to approve the Woodstock Festival:

“I hear you are considering changing the zoning law to prevent the festival. I hear you don’t like the look of the kids who are working at the site. I hear you don’t like their lifestyle. I hear you don’t like they are against the war and that they say so very loudly. I don’t particularly like the looks of some of those kids either. I don’t particularly like their lifestyle, especially the drugs and free love. And I don’t like what some of them are saying about our government. However, if I know my American history, tens of thousands of Americans in uniform gave their lives in war after war just so those kids would have the freedom to do exactly what they are doing. That’s what this country is all about and I am not going to let you throw them out of our town just because you don’t like their dress or their hair or the way they live or what they believe. This is America and they are going to have their festival.”

According to a 2016 article in “HaAretz,” Bethel residents were split on the idea as opponents began posting signs urging neighbors, “Don’t buy Yasgur’s milk…he loves hippies.” Yasgur was still pondering the property rental proposal when his own neighbors called for the milk boycott. That did it! He signed the agreement and thus the dairy farmer became a counter-culture hero.

He said at the time that he never expected the festival to be so large, but that “If the generation gap is to be closed, we older people have to do more than we have done.” Personifying the midah of chesed, Yasgur quickly established a rapport with the concert-goers, providing food at cost or even free. When he heard that some local residents were reportedly selling water to people coming to the concert, he put up a large sign at his barn on New York State Route 17B reading “Free Water.” Yasgur’s son Sam recalled his father telling his children to “take every empty milk bottle from the plant, fill it with water and give them all to the kids; give away all the milk and milk products we have at the dairy.” Yasgur believed strongly in freedom of expression, and was angered by the hostility of some townspeople toward “anti-war hippies.” Hosting the festival became, for him, a “cause.”

On the second day of the festival, Yasgur himself addressed the crowd: “I’m a farmer. I don’t know how to speak to twenty people at one time, let alone a crowd like this. But I think you people have proven something to the world, not only to the Town of Bethel or to the State of New York. This is the largest group of people to ever assemble in one place. We have had no idea that there would be this size group, and because of that, you’ve had quite a few inconveniences as far as water, food and so forth. Your producers have done a mammoth job to see that you’re taken care of and they’d enjoy a vote of thanks. But above that, the important thing that you’ve proven to the world is that a half a million kids, and I call you kids because I have children that are older than you…a half million young people…can get together and have three days of fun and music and have nothing but fun and music, and God bless you for it!”

Post-concert music memorialized Yasgur’s participation. The song titled “Woodstock” composed by Ms. Joni Mitchell, became a counterculture anthem. An excerpt of the lyrics: “I’m going down to Yasgur’s Farm; gonna join in a rock and roll band; got to get back to the land and set my soul free.” The music was the real message and even though it was delivered by performers who were certainly not at all role models of exemplary middos, the Woodstock festival became a cultural touchstone, and the phrase “Woodstock Generation” became part of the common lexicon. This counter-culture consisted primarily of average people who stood up for themselves against the “establishment’ with a force that was labelled “flower power.” There was a sense of social harmony and unity of purpose, especially regarding the major compelling event of that era, the war in Vietnam. Sometimes called the “Vietnam Song,” its performance was one of the signature moments at Woodstock: “Come on all you big strong men, Uncle Sam needs your help again. Got himself in a terrible jam, way down yonder in Vietnam. So put down the books and pick up a gun!” Yasgur himself summed up the disharmony of pro-war and anti-war factions in America with: “If we join them, we can turn these adversities that are problems in America today into hope for a brighter and more peaceful future.” The counterculture of young people wore bright colors, used illegal drugs, rejected traditional values and loved rock and roll music.

From a Jewish perspective, a significant number of concert attendees in Bethel made their way back home to the West Coast where they encountered a magnificent teacher; a singing Rabbi with a burning desire to bring close, those disaffected Jews for whom the Jewish establishment held no magnetism. Shortly before Woodstock, Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach, z”l, opened the House of Love and Prayer in San Francisco where he hosted thousands of the Woodstock Generation youth for ten years until he transplanted the entire community to Moshav Meor Modi’n in Israel. A trailblazer of the baal teshuva movement, he was asked why he gave that name to his yeshiva/outreach center. He explained, “Had I named it Temple Israel, none of my holy ‘hippalach’ would have showed up.”

One concluding thought from Rav Shmuel Zucker of Kehila Kedoshah of Ramat Eshkol, regarding the portion of Balak mentioned above. Kabbalah teaches us that the highest sparks of kedushah are found in the lowest places. Why do baalei teshuva have such an extraordinary passion for Judaism? It is because they came in contact with those sparks of holiness in the depths. Our role model for teshuvah is none other than King David. He descended from Ruth the Moabite, who is descended from an immoral, incestuous union. From that lowermost of places, will the holiest spark of all times emerge: the redemption of the Moshiach, a direct descendant of King David. May we carry this message forward as we focus on our personal teshuvah and the approaching High Holidays.

By Alan Singer

Dr. Alan Singer has been a marriage therapist in New Jersey and New York City since 1980. He has an 80% success rate in saving the marriages of couples on the brink of divorce. He counsels via Skype, blogs at FamilyThinking.com, and is the author of Creating Your Perfect Family Size (Wiley). His mantra: I am the last person in the room to give up on your marriage. Dr. Singer can be reached at dralansinger@gmail.com or (732) 572-2707.