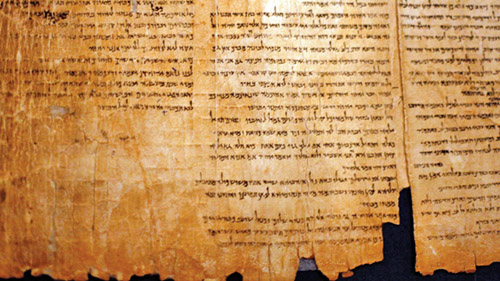

Among the ancient texts found in the Dead Sea region are both biblical and non-biblical texts. In this column, I am going to focus on the biblical texts.

Texts of a large percentage of Tanach have been discovered. (But nothing at all has been discovered from the book of Esther.) If you are interested in whether a text of a particular biblical verse has been discovered, there are resources you can consult. For example, I typically use the list in “The Dead Sea Scrolls After Fifty Years,” eds. Flint and Vanderkam (1999). (But there has been some material that came to light after that, including the first material from the book of Nechemia. Material continues to come to light periodically.)

The Dead Sea texts date from the third century BCE to the first century CE. This makes them older by many centuries than the earliest manuscripts of biblical texts that we had previously possessed. For example, the Aleppo Codex dates from the 10th century (and is missing most of the Pentateuch). The Leningrad Codex, which has a complete text of the Bible, dates to the early 11th century.

What happens when we examine these Dead Sea texts? There are differences from our Masoretic text but they are generally very minor. Most of the differences involve different spellings of the same word. Sometimes there is a different word altogether. For example, at Deut. 32:8, our Masoretic text has “yatzev gevulot amim le-mispar bnei Yisrael,” while the Dead Sea text has “sons of God.” Very rarely there are a few additional words. (One such example is at Deut. 32:43.) Sometimes the letters are the same, but the division of the letters into words differs.

Another interesting variant is in the first chapter of Eicha. Our Masoretic text of Eicha has an unusual inconsistency. The pe verse precedes the ayin verse in the acrostics of Chapters 2, 3 and 4, while the acrostic in Chapter 1 is in the traditional ayin-preceding-pe order. But in the Dead Sea text of Eicha Chapter 1, the pe verse precedes the ayin verse here too as well. In other words, verses 1:16-17 are in the reverse order from our Masoretic text, giving a consistent pe-preceding-ayin order throughout Chapters 1 through 4. (I have written much about this elsewhere.)

There is one glaring exception to our principle of minor differences between the Dead Sea and Masoretic texts. That is what I will discuss now. At the beginning of Chapter 11 of 1 Samuel, the Dead Sea text has a few extra sentences and it is very likely that they were there originally and got lost!

Here is our present text of 1 Sam 11:1-3:

“Nachash the Ammonite went up, and encamped against Yavesh Gilead. The men of Yavesh Gilead said to Nachash: ‘Make a covenant with us and we will serve you.’ Nachash the Ammonite said to them: On this condition will I make a covenant with you, that all your right eyes be put out; and I will make this a reproach upon all Israel. The elders of Yavesh said to him: Give us seven days respite that we may send messengers throughout the borders of Israel. Then if there will be none to deliver us, we will come out to you.”

Now let us read it with the added material from the Dead Sea text:

“Nachash, king of the people of Ammon, sorely oppressed the people of Gad and the people of Reuven, and he gouged out all their right eyes and struck terror and dread in Israel. There was not one left among the people of Israel beyond the Jordan whose right eye was not put out by Nachash king of the people of Ammon; except that seven thousand men fled from the people of Ammon and entered Yavesh Gilead. About a month later, Nachash the Ammonite went up….[continue with the paragraph above].”

In our Masoretic text, Nachash besieges the Israelites of Yavesh Gilead for no reason. Yavesh Gilead was on the west side of the Jordan and was not part of the territory that Nachash would have claimed as his own. With the added material from the Dead Sea text, we now understand why Nachash besieged Yavesh Gilead: seven thousand Israelites from Gad and Reuven had fled there!

It seems that an ancient scribe, while copying the text, erroneously jumped to a later word “Nachash” instead of to the initial word “Nachash.” This caused the omission of the material. This is a common type of scribal error.

Note also that in our Masoretic text, Nachash is introduced merely as “Nachash the Ammonite.” In contrast, in the Dead Sea text, he is introduced with a full title: “Nachash, king of the people of Ammon.” In Tanach, kings are typically introduced with a full title. This also supports the idea that the Dead Sea text is preserving the original material.

Critically, the additional material is also found in the ancient Greek text of the book of Samuel. It is also evident that Josephus (first century C.E.) had this material. See Josephus, Antiquities VI, paras. 68-69.

There are many other minor differences between the Masoretic text of Samuel and the Dead Sea text. One example is the height of Goliath. In our text (1 Sam. 17:4), Goliath is described as having a height of 6 amot. In contrast, in the Dead Sea text, his height is given as 4 amot. Also, at 1 Sam. 15:27, a tear is made in the garment of Samuel. (It is a very important tear, symbolizing the tearing away of Saul’s kingship.) Our text is ambiguous as to whether Samuel or Saul made the tear. In the Dead Sea text, the tear is explicitly attributed to Saul.

Finally, I will mention three other interesting but erroneous Dead Sea scroll variants: 1) The Dead Sea Isaiah scroll has “kadosh, kadosh” at verse 6:3, instead of our “kadosh, kadosh, kadosh.” (This scroll can be viewed online. Just Google: “The Great Isaiah Scroll.”) I was very surprised when I first came across this. Then I investigated further and found that many times, when our Masoretic text has a doubling of words, the Dead Sea texts have the word only one time. There must have been some ancient symbol on their words that indicated when a word, written once, was meant to count twice. Probably such a symbol was once found on one of the two “kadosh” words (either in the Dead Sea Isaiah scroll that survived or in earlier Dead Sea Isaiah texts no longer extant). 2) At the beginning of Psalm 145, the Dead Sea text has “tefilla le-David,” instead of our “tehilla le-David.” 3) The Dead Sea text of Psalm 145 includes a verse that begins with nun (“ne’eman Elokim be-devarav, ve-chasid be-chol ma’asav”). As is well-known, our Masoretic text of Psalm 145 has no nun verse. Most likely, the verse in the Dead Sea text was a later addition. The name used for God, Elokim, is not the name used in the rest of the Psalm, and “chasid be-chol ma’asav” is suspicious because it is already found elsewhere in the Psalm. See further the Daat Mikra (Mossad Harav Kook) edition of Tehillim, p. 579, note 23.

By Mitchell First

Mitchell First is a personal injury attorney and Jewish history scholar. His most recent book is “Esther Unmasked: Solving Eleven Mysteries of the Jewish Holidays and Liturgy.” He can be reached at MFirstAtty@aol.com. When copying material from another source, he is always careful to make sure there are no omissions.

For more articles by Mitchell First, and information on his books, please visit his website at rootsandrituals.org.