Imagine yourself in a pre-dystopian America, a near-parallel universe, where history as we know it is about to morph into alternative history. That’s exactly what happens in 1940 to the world inhabited by young Philip Roth and his family, all Newark, New Jersey residents. The creator of Philip’s fictional world is the renowned (and real) author Philip Roth, also a Newark native, who would have turned 90 this year. NJPAC’s March 19 staged reading of The Plot Against America, a marathon co-presentation with the 92nd St. Y, has rounded out a weekend-long celebration of his legacy.

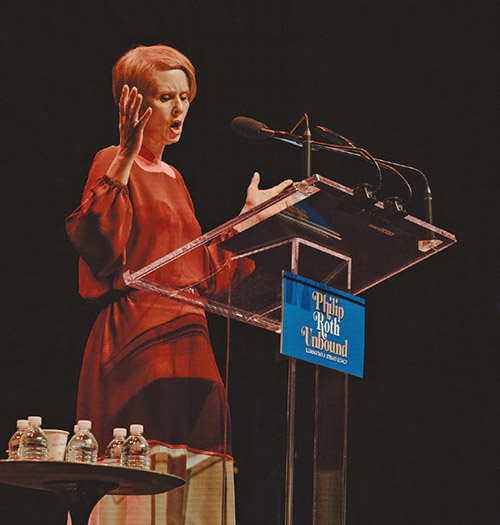

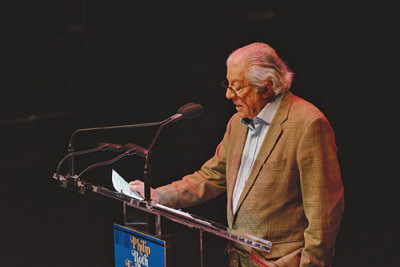

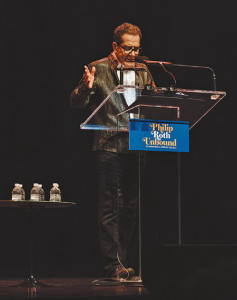

The distinguished cast of this staged reading draws from acclaimed stage, screen, and television actors, among them Sam Waterston, Tony Shalhoub, Peter Riegert, Cynthia Nixon, S. Epatha Merkerson, Eric Bogosian, Michael Benjamin Washington, Jane Kaczmarek, and Marjan Neshat. Each reads one chapter of the novel. Chapter 1’s United States, read by Washington, still largely resembles the Constitutional democracy established in 1789. As the story progresses from this initial tableau, each subsequent actor presents an incrementally darker and more uncertain future. Chapters 7, 8, 9, read respectively by Tony Shalhoub, Cynthia Nixon, and Sam Waterston, are perhaps the most distressing.

In young Philip’s America of 1940, Jews, at least at the outset, can live where they choose, work where they wish in professions of their choice, and go about their lives without disturbance. Their identity and religious practices are protected, and they can participate freely in elections and all manner of civic life. The Roths sleep at night without fear of being attacked, suddenly routed from their home, or having their businesses decimated, things that might have happened in their parents’ or grandparents’ time, in another country, during pogroms or under the Nazis’ rule. The Roths don’t keep a packed bag in the hall closet, just in case (Playwright Paddy Chayefsky once quipped that Jews must do so).

Political changes, though, like environmental ones, can be subtle and simultaneously insidious. When couched in the persona of a new, charismatic, and handsome political newcomer like superhero transatlantic flying ace Charles A. Lindbergh—whom most people believe can do no wrong—such changes are potentially pernicious. To interwar middle America, a storybook hero like Lindbergh, despite his deference to Hitler and acceptance of Nazi medals, is capable, or so he professes, of keeping the U.S. out of another war. There are none-too-subtle insinuations from Lindbergh and his supporters that Americans who oppose war’s high cost and human toll may be dragged into a Jewish-instigated conflict that will only benefit the latter.

The progressive Jewish community of Newark is disturbed by Lindbergh’s spiraling popularity. They both mistrust him and suspect that his inner circle, including like-minded Henry Ford, have every intention of rallying public opinion against Jews. They feel this way even prior to his airplane stunt-filled, last-minute candidacy, and a landslide win that unseats FDR as President.

The Roths have been genuinely apprehensive all along. Their neighborhood is in a buffer zone with biergartens and German Bund members in nearby areas. Despite the promotion offered to Herman Roth, Philip’s father, and an opportunity for home ownership, he declines the new promotion at his wife Bess’ urging because it will situate them among antisemites. Herman maintains that America’s historic freedoms will protect him, and to Bess’ chagrin, he publicly lambasts Lindbergh supporters whom he feels threaten those freedoms.

Lindbergh’s administration ushers in anti-Jewish sentiments, and a Jewish resettlement program, Just Folks. It is spearheaded by Rabbi Lionel Bengelsdorf, husband of Bess’ sister Evelyn. Bengelsdorf is mocked for publicly making Lindbergh “kosher” at a Madison Square Garden rally. This, and the specter of the Roths’ pending relocation to Kentucky are frightening, especially as seen through young Philip’s eyes. Instead, the Roths’ neighbors, widowed Mrs. Wishnow and her son Seldon, are sent to Kentucky, with deadly consequences.

The ensuing nationwide anti-Jewish violence is ever more frightening. Jewish presidential candidate Walter Winchell is assassinated at a rally. What is perhaps most frightening is when the Roths’ own household explodes violently. Herman confronts his son Sandy, Philip’s artistic older brother, who hides his stash of Lindbergh sketches and is a co-opted spokesperson for Just Folks’ plan to send Jewish teens and youth into remote areas. Herman’s nephew Alvin, a troubled idealist who returns home from Canada, is crippled from fighting the Nazis and full of rage. The final straw for Herman and Bess is when Rabbi Bengelsdorf and Evelyn try to get Sandy to attend a White House dinner where Von Ribbentrop is to be guest of honor. To her shame, naïve Evelyn dances with the Nazi.

Herman realizes only too late, when the borders with Canada are sealed, that Bess’ plan to move the family there is the best plan for their survival. True, the Roths cheat death when Herman quits his insurance job and rejects relocation to Kentucky, but Mrs. Wishnow has not. Herman observes firsthand how hatred literally fuels antisemitic fires when he travels with Sandy to Kentucky to rescue Mrs. Wishnow’s doubly orphaned son, Seldon, to bring him back to Newark, and to arrange for Mrs. Wishnow’s burial.

I will stop here, to avoid a spoiler alert and oversimplifying what is a very complex plot involving a kidnapping, Nazi attempts at blackmail, murders of Jews and pro-democracy rallies disrupted by incited mobs. A bit over the top, no?

Society was in quite a different place when in 2004, Philip Roth penned this novel, and even in early 2020, when HBO’s miniseries based on the novel first aired. But if one considers why first-rate arts venues, such as NJPAC and the 92nd St. Y, and sublimely gifted actors would choose to dramatize this novel, at this time, rather than any other of Roth’s works, it gives one pause. Does this work speak to these times, where antisemitism in this country is at an all-time high, particularly in the Metro New York area? Does antisemitism not manifest itself in both ugly jibes, conspiracy theories, and physical attacks? One should not read too much into Roth’s dystopian work, but on the other hand, it would be foolhardy to ignore it.

The fact that a highly regarded, diverse cast brings this timely story alive is laudable. The story of fascism, Nazism, the dissolution of civil rights and ultimately, violence is the story of the near destruction of European Jewry. Yet it is a cautionary tale for all people that should be retold by all people, at a precarious time in history and in reflection on Yom HaShoa.

Rachel Kovacs is an Adjunct Associate Professor of communication at CUNY, a PR professional, theater reviewer for offoffonline.com—and a Judaics teacher. She trained in performance at Brandeis and Manchester Universities, Sharon Playhouse, and the American Academy of Dramatic Arts. She can be reached at mediahappenings@gmail.com.