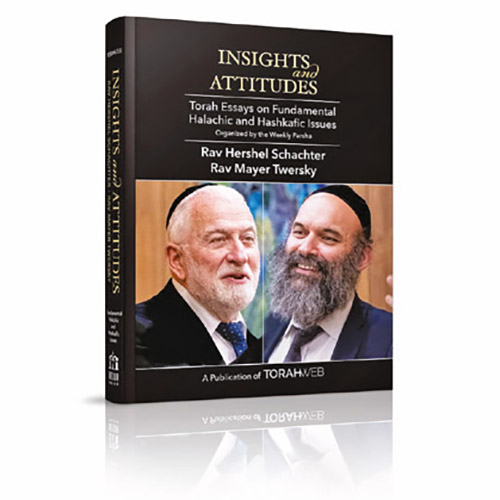

Editor’s note: This series is reprinted with permission from “Insights & Attitudes: Torah Essays on Fundamental Halachic and Hashkafic Issues,” a publication of TorahWeb.org. The book contains multiple articles, organized by parsha, by Rabbi Hershel Schachter and Rabbi Mayer Twersky.

The Gemara (Bava Kamma 83a) distinguishes between the Greek language and Greek philosophy. The Greek language was considered very elegant and, based on a pasuk in Chumash, the chachamim permitted a sefer Torah to be written in Greek (Megillah 9b). However, the chachamim frowned upon chochma Yevanis. The Gemara (Bava Metzia 83b) has a comment that olam hazeh is compared to nighttime. The Mesillas Yesharim (perek 3) explains this Gemara by pointing out that in the dark of the night people can make two types of mistakes. Sometimes they can see a human being from a distance and think mistakenly that it is a lamppost, and sometimes they can see a lamppost from a distance and think that it is a human being. Similarly in this world, it is sometimes very difficult to distinguish between right and wrong. Sometimes we will be facing a mitzva and think that it is an aveira, and sometimes the reverse. Dovid HaMelech says in Tehillim (119:105) that the words of the Torah are compared to a candle and a torch in that they give illumination. The Midrash (Yalkut Shimoni, ibid.) explains that when one begins to learn, the Torah only illuminates like a candle, but the more one learns, the more the gates of learning open up before him, and one thing leads to another until all of the gates open up and the Torah illuminates like a torch. Knowledge is compared to a light that illuminates the darkness. We daven to Hashem every day,

והאר עינינו בתורתך, i.e., we ask that we should succeed in learning Torah and thereby have the Torah illuminate our lives. When the pasuk says in Parashas Bereishis (1:2) that there was darkness all over the world, the Midrash has a comment that this is referring to Greek philosophy. The Midrash (Eicha Rabbasi 2:13) has a famous statement that there is much chochma to be found amongst all of the nations of the world, but not Torah. Torah means knowledge that guides us to know the difference between right and wrong, between mitzva and aveira.

It is said in the name of Rav Chaim Soloveitchik that in addition to the thirteen principles that guide us in deriving halachos by reading in between the lines in the Chumash, there is a fourteenth midda, namely sevara – logical analysis (based on Bava Kamma 46b). However, it is also recorded in the name of Rav Chaim Soloveitchik that he instructed his sons that they should not dare to suggest a sevara in learning before they complete all of Talmud Bavli with Rashi.7 Each discipline has its own self-contained logic. One cannot impose outside sevaras onto the Gemara. The sevaras have to flow from within the sugya.

The Gemara (Kiddushin 82a) tells us that Avraham Avinu volunteered to observe all of the mitzvos on his own even though he was never commanded to do so. The Midrash (Bereishis Rabba 95:3) elaborates on this idea and says that Avraham Avinu was able to understand on his own, intuitively, what the mitzvos were. Where did this intuition come from? It is traditionally understood based on the midrashim in Parashas Bereishis (Bereishis Rabba 1:1, and others) which state that when Hashem created the world He looked into the Torah first and created the world accordingly. So in a certain sense, the Torah was the blueprint of the world, and therefore if one looks at the world, he should be able to figure out what the blueprint was.

However, when looking at the world one has to take the correct approach to understanding it. The Greek philosophers did not believe in experimentation, since they felt that manual labor is only for slaves, and free men should always be involved in thinking only. Instead of collecting the data from experimentation, they would philosophize about everything, even physical phenomena (see Nefesh HaRav, p. 17). But one cannot impose outside sevaras on science, and therefore this approach led them to incorrect understandings.

It is well known that Rav Chaim Soloveitchik developed a new analytic approach to Gemara study. It is also well known that in order to answer many apparent contradictions in the Gemara, Rav Chaim would explain that the two Gemaras that seem to be contradictory are dealing with two different halachos. Many students of Gemara today imitate this style of Rav Chaim even when there are no contradictory passages in the Gemara, and they always will be splitting hairs in distinguishing between two dinim that seem to be identical. The Malbim in his commentary in Parashas Mikeitz points out that Pharaoh had two different dreams, and all of his advisors and scholars were explaining to him that the two dreams were “tzvei dinim” and contained two unrelated messages about the future. Yosef came and explained to Pharaoh that even though they were two different dreams, they actually comprised one big dream with one overall interpretation. Logical sevaras are certainly valuable, but they all have to flow from within the sugya and not be imposed from without.

In the biography of Rav Kook,8 it is related that when Rav Kook was a young boy, his father would often take him to Dvinsk (across the river from the city where they lived) to speak in learning with Rav Reuveleh Deneburger (the German name for the city of Dvinsk was Deneburg). Years later, Rav Kook would say over in the name of that gaon that one ought not suggest an original sevara unless it is either explicit or almost explicit in the Gemara or in the Rishonim.9

7 Kuntres Limmud HaTorah, p. 46, found at the end of Sefer Toras Chaim on Tanach.

8 Tal Haray”h, by Rav Moshe Tzvi Neriah, p. 18.

9 Ibid., pp. 66-67.

Rabbi Hershel Schachter joined the faculty of Yeshiva University’s Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary in 1967, at the age of 26, the youngest Rosh Yeshiva at RIETS. Since 1971, Rabbi Schachter has been Rosh Kollel in RIETS’ Marcos and Adina Katz Kollel (Institute for Advanced Research in Rabbinics) and also holds the institution’s Nathan and Vivian Fink Distinguished Professorial Chair in Talmud. In addition to his teaching duties, Rabbi Schachter lectures, writes, and serves as a world renowned decisor of Jewish Law.