In 2005, Rabbi Nati Helfgot edited a book called “Community, Covenant, and Commitment: Selected Letters and Communication,” which included many of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik’s correspondence.

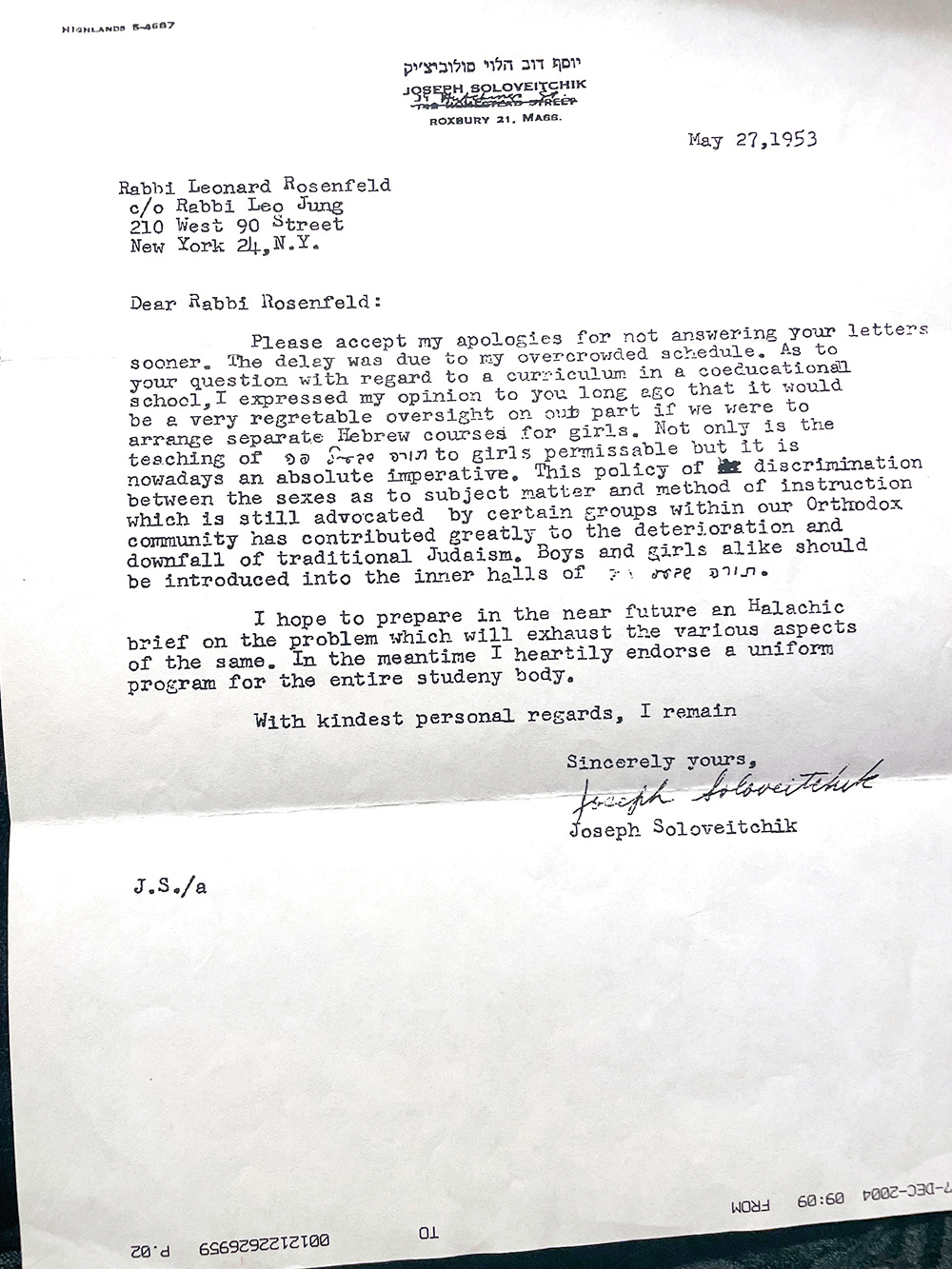

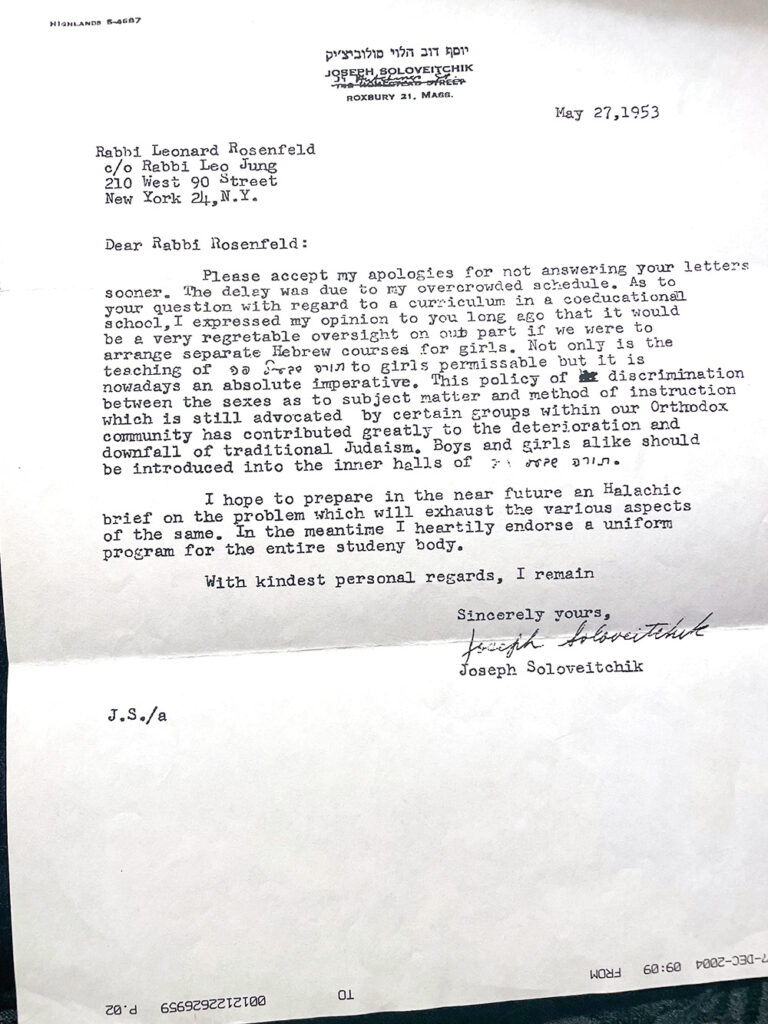

There was one letter in the book that created quite a stir when it was published: It was written in 1953 to Rabbi Leonard Rosenfeld, a student of the Rav, zt”l and a member of the board of education at the Hebrew Institute of Long Island (HILI), in answer to a question about whether female students could learn Gemara.

The letter seemed to clearly suggest that the Rav was strongly in favor. He said it would be a “regrettable oversight” if we were to arrange separate Hebrew courses for girls. He also stated the following in the letter: “Not only is the teaching of Torah she b’al peh to girls permissible, but it is nowadays an absolute imperative.”

For those in the Orthodox world who always believed the Rav felt this way—based on the curriculum that was established at the Maimonides School in Boston and his approval of Talmud courses for women at Stern College—the letter was conclusive proof of his position on the matter.

However, there is one person who was not surprised when he saw the letter in the book. Joseph Kaplan of Teaneck knew about this letter before Rabbi Helfgot’s book was published. In fact, he owns a copy of the original letter that was written to Rabbi Rosenfeld by the Rav.

Here’s the backstory of the famous letter as recounted by Kaplan … and how he was able to obtain a copy of the letter.

Kaplan grew up in Far Rockaway, New York, in the 1950s, and he and his family were close friends of Rabbi Rosenfeld, a prominent figure in the Far Rockaway community.

According to Kaplan, there were actually four separate letters that were communicated back and forth between Rabbi Rosenfeld and the Rav. Rabbi Rosenfeld first sent a letter to the Rav with a series of questions about teaching Talmud to girls. The Rav responded that he would not answer the questions unless he was assured in advance that the school administration would follow his recommendation.

Rabbi Rosenfeld then immediately responded with a letter, which was written in Hebrew, stating that the school would follow his recommendation. In a letter written to Rabbi Rosenfeld dated May 27, 1953, the Rav gave his recommendation, stating in no uncertain terms that it was not only permissible for girls to learn Talmud but that it was imperative.

A few interesting notes about the Rav’s letter. Although the question did not specifically address coeducation (HILI was already coed through fifth grade, and only separated boys and girls for limudei kodesh starting in sixth grade), it seems likely that the Rav was in favor of male and female students learning limudei kodesh together, even in the higher grades. He states that “it would be a very regrettable oversight on our part if we were to arrange separate Hebrew courses for girls.” However, later in the letter, he also speaks about not discriminating “as to subject matter and method,” which might mean that he felt boys and girls could be taught separately if the curriculum was completely equal.

Also fascinating was that the letter was sent “care of” Rabbi Leo Jung, the spiritual leader at The Jewish Center in Manhattan. Rabbi Rosenfeld was married to Rabbi Jung’s daughter … Why the Rav decided to send the letter care of Rabbi Jung as opposed to sending it directly to Rabbi Rosenfeld remains a mystery.

So how did Kaplan get a copy of the letter before it was first published? According to Kaplan, he had read about the existence of such a letter in a journal article—and decided to pursue it further. He contacted Ezra Rosenfeld, Rabbi Rosenfeld’s son, who confirmed that there was such correspondence, and had a copy of the original letter to his father that was signed by the Rav. Rosenfeld sent Kaplan a copy of the letter, which he now stores inside Rabbi Helfgot’s book.

What prompted the letter to the Rav in the first place? Was there a demand for Talmud classes for girls from parents? Did the administration want it? Kaplan isn’t 100% sure. “My guess is that the question wasn’t parent-generated but came from Rabbi Rosenfeld and some of the rabbis on the school’s board of education, which was a diverse group. Since HILI had a mixture of coeducation and separate-sex classes, and some of the same limudei kodesh subjects taught to girls and some not, it was different from the Rav’s Maimonides School model. So my guess is that some of the members of the board wanted clarification of whether they should follow the Maimonides model or continue as they had been.”

And here’s the irony to this whole fascinating tale. Notwithstanding the Rav’s very clear answer about giving girls the same limudei kodesh education as boys and the assurance by Rabbi Rosenfeld that the school would follow his recommendation, nothing changed. Kaplan explained, “The system continued exactly as it was at HILI, with boys and girls continuing to get the same limudei kodesh education in coed classes through fifth grade and from sixth grade on in separate-sex classes. Girls received no Gemara education whatsoever, despite the Rav’s very strong admonition that it was imperative that they receive it. Bottom line: The letter was ignored in practice. I’m not sure why the school completely ignored the Rav. It most probably had to do with administrators and/or teachers balking at the change, but sadly that’s a story that remains untold.”

Despite the Rav’s clear statement about teaching girls Talmud, there are still individuals today who believe that the Rav’s position was a b’dieved, and that he only recommended this to keep day schools afloat, and that l’chatchila he believed girls should not be studying Talmud. Kaplan strongly disputes this theory: “Whatever the Rav’s ideas were when he created Maimonides, the school would have done whatever he wished. He and his wife were directly in charge. So if he really wanted separate boys and girls classes, or even wanted separate limudei kodesh classes, or even just separate Gemara classes, he only had to say the word. But he didn’t. The strong language in his final response in the letter certainly doesn’t sound like he felt it was a b’dieved.”

Was the Rav’s letter considered psak or just friendly advice? Kaplan said, “I think the difference between ‘psak’ and ‘opinion’ is a red herring. It certainly sounded like Rabbi Rosenfeld was asking for psak. And the Rav’s first letter, in which he said that he wouldn’t answer the questions until he was assured the advice would be followed, certainly sounds like he was giving psak. On the other hand, the Rav often did not give psak to his musmachim; rather he gave them advice and told them that he hoped he taught them to think for themselves. My takeaway is that reading all the correspondence in context, it was closer to psak than advice.”

Michael Feldstein, who lives in Stamford, CT, is the author of “Meet Me in the Middle” (meet-me-in-the-middle-book.com), a collection of essays on contemporary Jewish life. He can be reached at michaelgfeldstein@gmail.com.