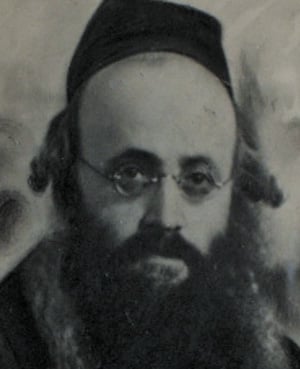

Some editions of Chovat Hatalmidim, a volume authored by the Piasecznier Rebbe, Rabbi Kalonymus Kalman Shapira (1889–1943) of blessed memory, includes the portrait of this saintly chassidic Rebbe. Ever since my childhood, the original of this portrait hung in my parent’s living room. Subsequently, it was copied with my parents’ permission and reprinted in many books of Jewish thought.

How did this picture come into my family’s possession? The following account is based on the story handed down to me by my late parents, Pnina and Ya’akov Friedenberg, and my late uncle, Bezalel Schreibhand.

My maternal grandfather, Rabbi Meir Dovid Schreibhand, was a Rav and Dayan in Warsaw, Poland. He was the Rav of Bes Hakneses Adas Jeszuryn Szeni located at 32 Muranowska. Rabbi Schreibhand; his wife, Chaya Liba, and their children lived at 40 Zamenhoff in Warsaw and were Piasecznier Chasidim.

My grandmother was a first cousin of Chana Bracha, the Piaseczner Rebbe’s mother. Thus my mother was the Rebbe’s second cousin. The family relationship was very close as demonstrated by the fact that my uncle Shalom’s aufruf was held in the Piaseczner Shtibel, 5 Dzilna Street, on Shabbat Parashat Mishpatim in 1936.

In 1935, my mother, Pearl Rochel (later known as Pnina), moved to Eretz Yisrael. Over the years she kept in touch with her parents and siblings, especially with her younger brother Bezalel.

One winter night in 1939, my mother had a dream that her parents wrote her and requested that she return to Warsaw for a family visit. In the dream, she complied with her parents’ request but when she wanted to return to Eretz Yisrael her parents forbade her because she was a single girl and they were concerned that she was not yet married. Upset by the dream, she vowed that she would never return to Poland.

Amazingly, a week after the dream, my mother received a letter from her parents asking her to “come home for a visit.” With the dream still fresh in her mind, she was shaken. She responded to their invitation in Yiddish: “Tayere tate und mame. A yid darf voinen in Eretz Isroel. Ich fur nisht tzurik zi Poilen. Kumt kain Eretz Isroel” (Dear Father and Mother, A Jew must live in Eretz Yisrael. I am not going back to Poland. Come to Eretz Yisrael).

This letter was followed by further communications, but my mother was determined to stay in Eretz Yisrael. At no point did my mother tell her parents about her dream.

On Purim of 1939, my uncle Betzalel participated in the Purim Seuda at the Piasecznier Rebbe’s Tish. During the course of the Seuda, the Rebbe declared: “Ich hob moyire fin der kumendicke Yomim Noro’im” (I fear the coming High Holidays, i.e., Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur). My uncle never forgot this message, but at the time, did not understand its significance.

Several months later, my grandparents asked Bezalel to travel to Eretz Yisrael to convince his sister to return to Warsaw. My uncle agreed. Before departing on his voyage, Betzalel asked an older brother, most likely the oldest, Yankel, who owned a side-view, profile photograph of the Piasecznier Rebbe, to let him borrow it for the duration of the trip, perhaps to serve him as a talisman for protection. As very few pictures of gedolim were available at the time, even side-views, the picture was indeed a precious commodity.

Upon arriving in Israel in September of 1939, Betzalel learned that the German army had invaded Poland and World War II had begun. Suddenly, he understood the Rebbe’s premonition at the Purim Tish.

Based on the tragic news, it became clear to both my uncle and my mother that they were both destined to stay in Eretz Yisrael, and to be saved there from the Holocaust. Ultimately, my grandparents, my aunts and uncles all perished in the Warsaw Ghetto and other notorious concentration camps. “Hashem Yikom Damam.”

In 1942, my mother married my father, Ya’akov Friedenberg, whose family members were Modzitzer Chasidim, and established their residence in Jerusalem. In the Modzitzer Shtibel, my father befriended Chaim Fryman, a gifted artist. At my father’s request, Chaim set out to recreate a full facial view of the Rebbe’s face from the portrait that my uncle brought to Israel. When the painting was finished and shown to my uncle he exclaimed in excitement: “Dus is der Rebbe!” (This is the Rebbe).

Although known only to a few friends and relatives, I am privileged to record the authentic saga of the now famous portrait of the Piasecznier Rebbe, Rabbi Kalonymus Kalman Shapira, which I inherited from my late parents and which now graces our living room.

Rav Kalonymus Kalman Shapira zt”l, was born on the 19th of Iyar, 5649, and murdered at the age of 55 in the Budzin labor camp, in the Lublin, Poland region on the 4th of Cheshvan, 5704 (November 2, 1943). His teachings, including Chovat Hatalmidim and Aish Kodesh, written in the Warsaw Ghetto, have been crucial in the revival of the Jewish people’s interconnection with Hashem before, during and after the Holocaust. Until today, his educational guidance and Torah have inspired thousands to abandon a superficial approach to Yiddishkeit and deepen their connection with Hashem using the full spectrum of their emotional and intellectual faculties. May the Rebbe’s meaningful teachings continue to inspire future generations.

Recent books that explore the teachings of the Piasecznier Rebbe are The Holy Fire: The Teachings of Rabbi Kalonymus Kalman Shapira by Nechemia Polen and Warmed by the Fire of the Aish Kodesh by Rabbi Moshe Weinberger.

By Pinhas Friedenberg

Pinhas Friedenberg and his wife, Doris, are active members of the Rinat community of Teaneck. Pinhas has served as a registrar at major universities and Doris is a beloved teacher at Yavneh Academy. They have two sons pursuing higher education of whom they are very proud.