.jpg)

Jerusalem—Until the middle of the 20th century, the Jews of Ethiopia lived in almost complete isolation from other Jewish communities across the globe, preserving and developing distinctive religious traditions not found in the rest of Jewry. In the 1980s they began leaving Africa for Israel in the thousands, and at present almost none remain in Ethiopia.

In addition to other challenges their emigration from Ethiopia to Israel entailed—such as transitioning from village life to living in a technologically advanced society, and becoming a minority as far as their skin-color—Ethiopian Jews also practiced a form of Judaism that was unfamiliar to most of their coreligionists.

Among Ethiopian Jewry’s unique traditions is the Sigd, an annual holiday that will be celebrated on October 31 this year. On that day, thousands of Ethiopian Jews from across Israel will ascend to Jerusalem, primarily to the Armon Hanatziv Promenade that overlooks the Old City. Since 2008, the Sigd has been an official Israeli state holiday, though it continues to be celebrated mainly by the country’s Jewish community from Ethiopia, which now numbers about 130,000.

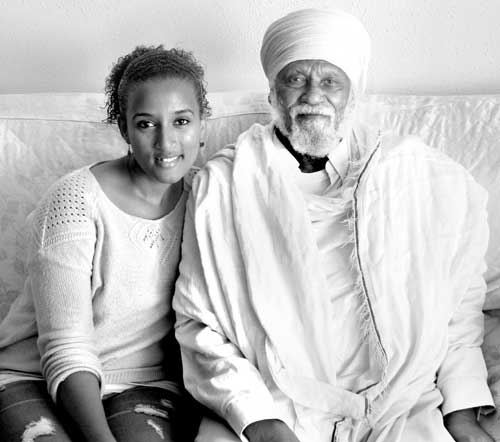

On the morning preceding last year’s Sigd celebration, I visited the apartment of one of the oldest qessotch—priests who are the traditional spiritual leaders of Jews from Ethiopia. Born in the Gondar district of Ethiopia, 79-year-old Qes Emaha Negat moved to Israel in 1991, and now lives in the sea-side city of Netanya. Clothed entirely in white, his head wrapped in a white turban, and speaking Hebrew and Amharic, Qes Emaha recounted the biblical events in which the Sigd is rooted.

Sigd means “prostration” or “bowing down” in Ge’ez, the ancient Ethiopian liturgical language. The holiday commemorates and is patterned after events described in the biblical Book of Nehemiah. Chapter 9 records that on the 24th of Tishrei, “the Israelites gathered together, fasting and wearing sackcloth and putting dust on their heads. Those of Israelite descent had separated themselves from all foreigners. They stood in their places and confessed their sins and the sins of their ancestors. They stood where they were and read from the Book of the Torah of the Lord their God for a quarter of the day, and spent another quarter in confession and in worshiping the Lord their God.” The 6th century BCE gathering in Jerusalem culminated in the Jews publically recommitting themselves to the covenant between God and the Jewish people.

Joined by his wife, Zena Malasa, as well as by his granddaughter, Facika Savhat, Qes Emaha paused in his explanation of the holiday’s origins. He expressed concern that the Sigd has been losing its religious significance in Israel, and is more and more becoming a cultural event. October or November serve up an array of activities and programs connected with Ethiopian Jewry in the lead-up to the holiday, but many of them lack a religious framework. “Whoever goes to Jerusalem tomorrow with pure thoughts, candidly, will celebrate the holiday as it should be,” he said. “One must come to serve God and to pray. It is not just a social gathering.”

“But the prayer and the learning are done in Ge’ez, with a translation into Amharic,” the qes’s granddaughter pointed out to him. “How can young people find themselves there?”

Qes Emaha acknowledged that there was a barrier. “But those who come can take the memory of the experience with them and they will arrive at an understanding of the holiday when they mature,” he insisted. “It is also possible to have learning for the young people in Hebrew when families come.”

One of the first worshipers I encountered in Jerusalem on the morning of the Sigd celebration was Adgo Salehu. Dressed in white and draped in a red, yellow and green sash, Salehu arrived early at the Armon Hanatziv Promenade, where he located a prime spot to situate his tripod-mounted video camera and record the celebration. On finding out that I had traveled from the United States to participate in the holiday, he smiled broadly. “This day of prayer must not be only for the Jews from Ethiopia, but for the whole nation,” Salehu said. “It is important that the Sigd holiday develops and expands, and that more people join in its celebration.”

During the Sigd, dozens of qessotch assemble at the Armon Hanatziv Promenade on a specially-constructed platform adorned with the flags of Israel and Jerusalem. Some are dressed all in white; others wear cloaks of embroidered gold, blue, purple or black, adorned with large Stars of David. In addition to multi-colored parasols, the qessotch carry fly whisks and walking sticks, all three items representing their honored position. Behind them, the stone walls of the Old City glimmer in the sunlight.

Beneath a “Welcome to the Sigd Holiday” banner written in Hebrew and Amharic, the qessotch chant prayers in Ge’ez and Agaw. Biblical passages, including those describing the giving of the Ten Commandments on Mount Sinai and the renewal of the covenant by the Jews who returned from the Babylonian exile, are read to the congregation in Ge’ez, and then translated into Amharic, the first language of many members of the Jewish community from Ethiopia.

By the afternoon, the hours of worship and study at the Armon Hanatziv Promenade build to a religious crescendo. The tone of the Sigd chanting becomes increasingly joyous, and the qessotch sway, accompanied by rhythmic drumming. Women raise their hands, ululate and prostrate, pressing their foreheads to the ground.

When the qessotch descend from their platform at the conclusion of the services, they are quickly surrounded by hundreds of congregants, who accompany them with jubilant cries, applause and trumpet blasts to a nearby tent, there to break the fast communally following the annual renewal of the covenant.

“I would suggest that Jews in Israel and the rest of the world adopt this holiday,” Rabbi Hadane, the chief rabbi of the Jewish community from Ethiopia, said to me outside the tent. “Our forefathers in Ethiopia always prayed to return to Jerusalem and always prayed in the direction of Jerusalem. We are here, but the vast majority of the Jewish nation is still in the diaspora, and this day and these prayers are very important for ingathering the exiles.”

Also outside the tent was 29-year-old Ethiopian-Israeli photographer Gidon Agaza. Throughout the morning and afternoon, Agaza snapped pictures of the qessotch and other worshipers. “I have been attending [the Sigd] for 13 years,” he said. “Each and every year that I come, I am moved anew to see the mothers praying from their hearts.”