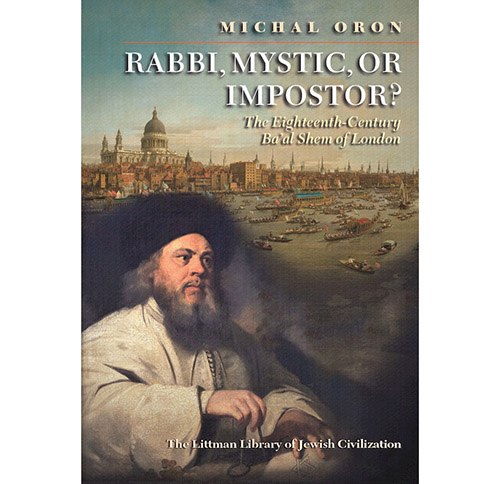

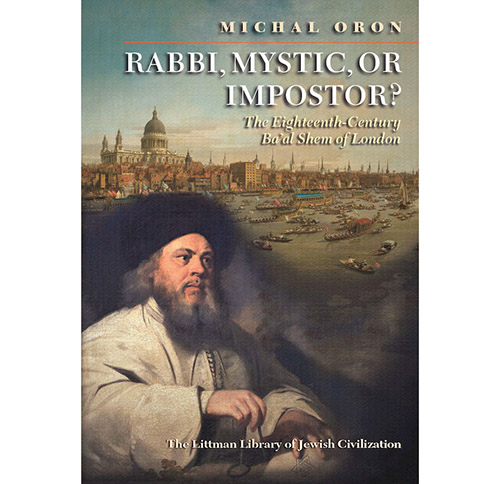

The portrait of Rabbi Shmuel Yaakov Falk (1710-1782) known as the “Baal Shem of London” is often confused with that of Rabbi Israel ben Eliezer, the Baal Shem Tov and founder of the chasidic movement.

Former Chief Rabbi of Great Britain Rabbi Dr. Herman Adler (1839-1911) wrote several fascinating biographical sketches of Rabbi Falk for the Transactions of the Jewish Historical Society of England. When perusing his papers, he was surprised to find that Falk referred to himself in his diary as “the son of Raphael the Sefardi.” Initially, Adler prudently pointed out that the term “Sephardi” was often used by and for the (then) newly emerging sect of chasidim who were often called “Sephardim” or “Anshei Sfard” (because they prayed in a modified Sephardic rite). Although initially reticent, in a later republishing of the same article, Adler provides more clues as to the origins of Falk. This time no mention of a possible chasidic connection is made. Adler merely wonders, “It is unclear why and how he [Raphael the Sephardi] received this appellation [Sephardi]. Had he immigrated from Spain or Portugal?” and adds that “Falk’s Sephardic pronunciation of Hebrew may have been due to his parentage.” Additional evidence seems to bear this out. In the comment on that passage, Adler writes that Falk gave his name in his commonplace book as חיים שמואל יעקב דפאלק טרדיולה לנידו (Chaim Shmuel Yaakov de Falk Tradiola Laniado) and wonders whether he might possibly be related to the Laniados, a Sephardic family that settled in Italy and the Middle East. The answer seems to be in the affirmative.

Falk’s personal assistant was a Polish Jew by the name of Zvi Hirsch of Kalisz (parenthetically, Kalisch’s descendants later anglicized their name to Collins and assimilated into British gentility), who kept a personal journal where he described his master’s daily activities and magical experiments. The journal is an intimate window into Falk’s life; it describes Falk’s frequent quarrels with his wife. One entry records an incident where he wanted to throw a dish of food at her, saying it was cooked so badly that any Sephardi who tasted it would laugh outright…

Falk’s unlikely Sephardic ancestry is also briefly mentioned in the recently published book by Michal Oron, “Rabbi, Mystic, or Impostor” (which is an English translation of an earlier work published in 2003): “His father, Rabbi Joshua Refael the Sephardi, was apparently descended from a Spanish New Christian family which, having arrived in Poland in the 16th century, returned to Judaism… Falk is also the name of a family of distinguished lineage that included Rabbi Joshua ben Alexander Falk, author of Sefer Meirat Einayim (Sema), and Rabbi Jacob Joshua ben Zvi Hirsch, author of Penei Yehoshua.”

Oron’s translation and annotation of Falk’s diary (Liverpool University Press, 2020) is a fascinating window into the lives of both Falk and his associates. Oron maintains that Falk was “probably born in Podhajce (then in Poland, now in Ukraine).” While there is no proof that Falk was a Sabbatean, he was close friends with the famous Sabbatean Moses David of Podhajce who stayed at his home in London for a brief period.

Falk’s family had initially relocated from Poland to Furth in Germany where Samuel began practicing practical Kabbalah. This led to his eventual arrest where he was charged by a court in Westphalia with practicing black magic. He was sentenced to death but managed to escape to London.

There Falk established himself as a miracle worker and a sort of folk healer. Both Jews and many Christians, especially from the upper class, visited him. The German count Von Rantzow mentions meeting Falk in his memoirs. He characterized Falk as “a renowned prince and High Priest of the Jews.” He mentions that his father had told him that Falk considered himself “to be a scion of the line of King David.” Rantzow also provides a possible clue as to Falk’s background when he claims that when Falk fled Germany, he went to England “where the Portuguese Jews received him as their prince and supreme leader.”

As we shall see, that statement is certainly not factually true; Falk, when given the opportunity to do so, refused to become a member of any of London’s Jewish congregations. Oron correctly characterizes “his aversion to communal factionalism and his unwillingness to belong to any ethnically defined community.” Yet at the same time, Falk eventually became one of England’s greatest philanthropists and left very generous bequests for both the Sephardic and Ashkenazic communities of London.

Falk’s aforementioned diary was examined by the author who described it as consisting of 59 folio pages, mainly in Hebrew, and mostly written in Spanish rabbinic script. Before Oron’s publication of it (initially in Hebrew, by Mossad Bialik, 2003), the diary had never been published in its entirety. It contains an eclectic collection of recordings of events, recipes for cakes, remedies (one of his recipes involves melting bone marrow along with butter and other ingredients to make plaster. This seems to be in contravention to the laws against mixing milk and meat, which perhaps lend credence to those who would cast him as a Sabbatean. Parenthetically, Kalisz’s diary has a cure for epilepsy that involves burning an owl and eating the ash), and Kabbalistic formulae and more.

As mentioned before, Falk’s personal assistant, Tzvi Hirsch of Kalisz, likewise kept a diary. One tragicomic excerpt from that diary paints a portrait of someone who was at least partially acculturated into the Ashkenazic world. Apparently Falk was very fond of his kugel (a traditional Ashkenazic dish partaken in honor of the Sabbath meal). On the 12th of Shevat, he lashed out with great harshness at his wife for ruining his favorite kugel..

Someone once quipped to me tongue-in-cheek that the best/most interesting Ashkenazim are/were Sephardim.

While, as mentioned, Falk’s diary is written in Sephardic cursive, some of it was also written in Ashkenazic style. Also of interest is the way he sometimes translated and transliterated words. For instance, he uses the German or Yiddish term kessel to describe coffee and tea, and for pasta he used the Yiddish/German word lokshen.

What is also interesting is that several of his disciples and visitors came from Zamosc in Poland (one of them, for instance, was Ezekiel ben Shalom, a leading Sabbatean). As I’ve written in greater length elsewhere, Zamosc hosted a Sephardic community beginning in the 17th century that apparently lasted in some form for several centuries.

In Falk’s entry for the 23rd of Tevet, he mentioned a letter he sent to one “Solly Nordah.” Oron conjectures that this may allude to Solomon ben Abraham Laniado who was a preacher in Venice in the 17th century. Could this be a Laniado relative with whom he kept in touch?

Also, a list of books that always accompanied Falk in his travels included Sefer Emek Yehoshua, a book of questions and answers on the weekly Torah portions and halachic matters, by Rabbi Joshua ben Juda Leib Falk who lived in the 17th century. Curiously enough, the author, like Samuel, was born in Poland (Lviv) where he was a preacher, and eventually relocated to Hamburg, Germany; perhaps this Falk was likewise a prominent relative?

While little reference is made to his father Raphael “the Sephardi,” one entry for the 25th of Nisan is intriguing. He mentions seeing his father in a dream. He refers to him as “R. Joshua Raphael Falker Falk.” Falk continues that “for 35 years I had heard nothing of him…and then he went upstair to my synagogue… I said to my students, ‘Beware of his silence and do not let him deceive you…for none is greater than he is in Torah and in the sharpness of his tongue…”

All told, Falk’s diaries only add to the complexity of a figure who was undoubtedly anything but conventional. While Tzvi Hirsch claims that he was miserly, Falk in his will left a great fortune to be distributed to the poor as well as to the Sephardic and Ashkenazic communities of London. His bequest was so large that apparently down to the present day, the chief rabbi of the UK still receives an annual amount from this endowment in addition to his salary.

The author is an independent researcher of Jewish history and a translator of Hebrew text (he also misses being a scholar-in-residence during non-Covid times). He can be reached at yoelswe@gmail.com.