When the gyms shut down this year in March and it looked like all of my triathlons were going to be canceled, I had two problems to resolve:

Where was I going to swim?

What was going to motivate me to keep swimming?

The “where” was easier to resolve. Every year I do a New Year’s Day polar bear swim at Coney Island and I swim laps at the next beach over during the summer. Why not combine the two locations?

In the movie “Titanic,” Jack was partially submerged in water that was about 32 degrees. He froze to death in about 15 minutes.

(Someone double-check the film footage.)

My coldest polar bear swim was in 2018 when the water was 37 degrees.

I only lasted 56 seconds before I had to get out.

(It took 30 minutes and a gallon of hot cocoa to warm you back up.)

By mid-May of this year, the water temp had risen to 58 degrees. Not exactly tropical, but bearable in a neoprene wetsuit.

For the “what,” I signed up for English Channel Virtual Challenge.

(Just how far across is that swim?)

Twenty-one miles.

(How far can you actually swim without stopping?)

Only one way to find out.

(But you might drown.)

I always swim along the shore to minimize the risk. I mean 1,000 meters offshore are the boat lanes.

(Are you trying to swim across the bay to Breezy Point?)

No. I mean, yes, I mean kinda. I really want to, but the ferry passes back and forth all day and getting caught in the prop wash of the 6:15 ferry could ruin your day. So, I swam parallel to the shore where I knew I was safe.

(What if you got a cramp?)

That’s happened before. I simply rolled over on my back and used my hands to make it back to shore.

Besides, I have my neon swim buoy tethered to my body.

(Isn’t that so other swimmers can see you?)

Yes, but it also makes for a lovely pillow when you are floating on your back.

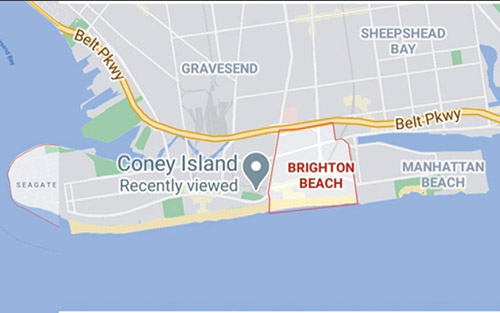

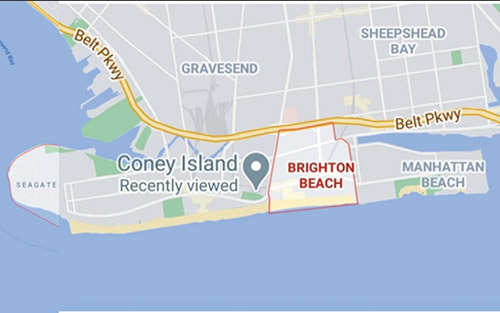

The area of Brooklyn where I swim is called Brighton Beach. The name dates back to 1878 when the developers of this resort hoped associating with the English seaside resort of the same name would be good for business. This Brooklyn beach is in the center of a series of connected beaches: Manhattan-Brighton-Coney-Sea Gate.

Manhattan Beach is a private beach, so I always park in the public lot at Brighton Beach 4. At 6 a.m. in the morning, it is the only place I am guaranteed to find parking within walking distance of the water.

Five hundred meters down the shore is the beginning of Coney Island Beach.

A thousand meters is the Coney Island Aquarium.

Seventeen hundred meters is the famous parachute drop of the Coney Island Amusement Park.

Two thousand, one hundred seventy five meters is the Coney Island Pier.

The first couple of swims of the summer were 1,000 meters down the shore and another 1,000 back. My Garmin GPS watch was tracking my progress, but the large gray building of the Coney Island Aquarium that rose above the shoreline told me I had reached 1,000 meters of swimming. As with most endeavors I start, these swims started to get longer. The 1,000-meter turnaround became a 1,500-meter turnaround. The 1,500 became 2,000. Soon my focus switched from logging enough miles for the English Channel Virtual Challenge to seeing just how far I could swim. I didn’t want to swim in circles until I was exhausted. No, if I was going to swim until I was exhausted, I needed somewhere to swim to. That is when the Sea Gate Lighthouse became my new obsession. It was the furthermost point I could swim to before I was truly swept out to sea. I estimated its distance to be three to four miles from Brighton Beach.

To reach my goal, I had to go beyond “The Wall.”

For years, the pier was a symbolic wall. The Chinese used to refer to the wilderness beyond the Great Wall of China as “ku wai,” beyond the gates. A barren place where demons lived.

As a group, my friends and I had never swum under the pier, because we considered the other side to be no man’s land. On our yearly 5k swim, this was our turn around point since none of us knew what lay beyond the concrete structure in “ku wai.” Were there any sharp jagged rocks just below the surface? How did the tides act where the waters mixed with the currents from the Verrazano Narrows? For me, The Coney Island pier was “the wall” that separated the known from the unknown.

By the end of June, I decided it was time to see what lay beyond “the Wall” in ku wai.

David Roher is a USAT certified marathon and triathlon coach. He is a multi-Ironman finisher and a veteran special education teacher. He can be reached at: TriCoachDavid@gmail.com