I visited Ephraim Kholmyansky in Moscow in October 1987. It was my second trip to the USSR to help encourage Jews, bring hope, make personal connections and smuggle in no small amount of things to help them, but that could have put me in some big trouble with the KGB.

I knew about Ephraim before, as I spent much of my early adulthood engrossed in the movement to free Soviet Jews. So, for me, I was meeting one of my heroes. But as much as I thought I knew Ephraim through my activism and his prominence (he had recently been in a Soviet prison) and as much as I understood how bright and thoughtful he was, until I read his autobiography, “The Voice of Silence,” I didn’t know how much I really didn’t know. And I didn’t know how important he, and what he did in the 80s for our people in the Soviet Union, really was—and still is.

In 1966, Elie Wiesel wrote “The Jews of Silence.” A generation after the Holocaust, Wiesel put a spotlight on Soviet Jews, whose culture was being erased by force. That was a catalyst for Western Jews (to whom he was also referring as being silent) to awaken to the imperative to help millions of Soviet Jews imprisoned behind the Iron Curtain and facing persecution daily. He wrote, “What torments me most is not the Jews of silence I met in Russia, but the silence of the Jews I live among today.”

Ephraim Kholmynasky and others were some of the early underground Hebrew teachers playing a pivotal role in the awakening of Jewish identity in the USSR. They established a network of people who studied Hebrew intensively and even became certified as teachers, (a significant story which he recounts). Then they fanned out across the USSR’s distant republics to teach more teachers in what they called “The Cities Project.” Ephraim and others whom he described as brothers and sisters with the same mission, gave voice to the Jews of silence in the USSR, and inspired those of us in the West not to be silent either. No longer were Soviet Jews being robbed of one more precious aspect of their identity—their own modern language.

But it’s not like they simply rented space at a local college or used a meeting room in one of the Soviet Union’s few synagogues. No. Teaching Hebrew was illegal. They knew the risks they were taking. They were not the first to do it, nor the first to face the consequences. But they were the first to build a systematic curriculum and underground network through which to teach the language beyond Moscow and Leningrad. It all had to be done in as much secrecy as possible, under the radar of the ever-present KGB, so as not to put the teachers, students or their organized network at risk.

As hard as it is to imagine today when millions of Israelis—Jews and Arabs—speak and interact in all aspects of life using our ancient language that was reborn in modern Israel, along with Jewish children learning Hebrew in day schools and synagogues around the world, in the Soviet Union, Hebrew was illegal.

Anticipating his arrest, Ephraim chronicles his “training” for that inevitability. Using his analytical skills, he was able to have a playbook in his mind as to how he would respond and behave. He was one of the “lucky” ones, only sentenced to 18 months, largely in part to his uncompromising hunger strike. It is jarring still to think of that as being lucky, or of his considering it then to be a victory.

Reading “The Voice of Silence,” I reflected about the juxtaposition of my life to Ephraim’s, thousands of miles—and another world—away. In that parallel universe, Jews were in the midst of an awakening that included studying Hebrew, embracing Jewish culture and religion, and pre-teens also secretly preparing for their bar and bat mitzvah. In the late 1970s I was going about my bar mitzvah preparations, and somewhat rote rituals from studying with a tutor, to attending afternoon Hebrew school, and of course the pilgrimage to Barney’s to buy the required (brown) bar mitzvah three-piece suit.

While I was on the verge of becoming a bar mitzvah, Ephraim was completely engrossed in studying Hebrew. “From the fall of 1977 on, Hebrew lessons became the highlight of my week— three or four hours once a week with only a short break for tea.” I surely never would have considered it a highlight of my week. And, ironically, it was even my father’s first language.

I had the luxury of finding my Hebrew and religious studies inconvenient, even annoying. On the other side of the world, any inconvenience or annoyance was the result of the secretive nature of their studies, and the consequences which could include being fired from one’s job, expelled from school, and imprisoned for one of a variety of trumped-up charges. In Ephraim’s case, the KGB planted a gun and ammunition in his apartment, which he recounts in depth.

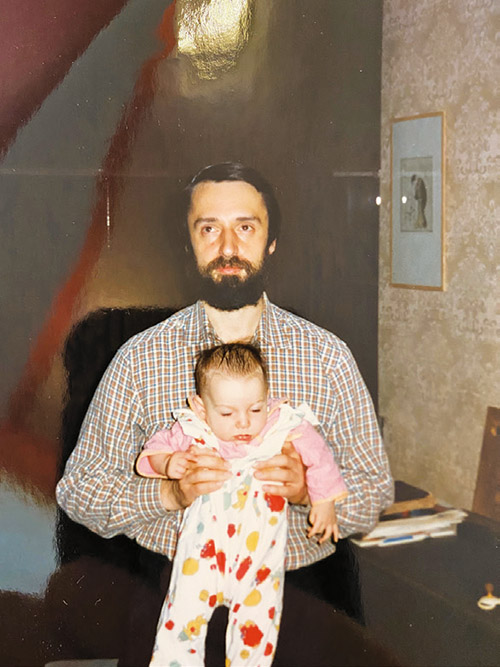

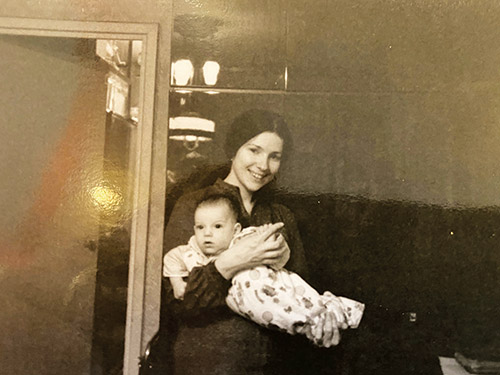

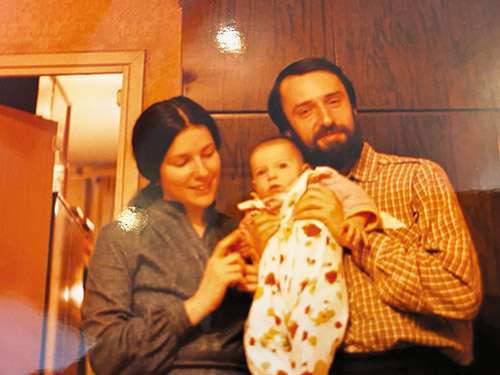

Since making aliyah, I was fortunate to reconnect with Ephraim. Albeit that he, the Hebrew teacher, and I speak in English, he’s no less the bright and thoughtful person I met in Moscow. All but one of his children were born in Israel. For me, all but one of mine were born in the U.S. We’ve spoken about our kids and how for his, it’s hard for them to imagine he ever suffered like that. For my kids, even knowing what I did, it’s hard for them to understand what I was doing and why it was so important.

But it’s that incredible ingathering of the Jewish people from the corners of the world, understanding and appreciating the struggles that were required to get here, much more than which of my kids got the window seat, which makes “The Voice of Silence” so important. Our children and grandchildren need to know that whether walking through the Sudanese desert, being flown on magic carpets or resisting the KGB, our history is intertwined—as is our destiny. “The Voice of Silence” is an important part of our history—and who we are today.

Jonathan Feldstein, formerly of Teaneck, made aliyah in 2004 and now lives in Efrat.