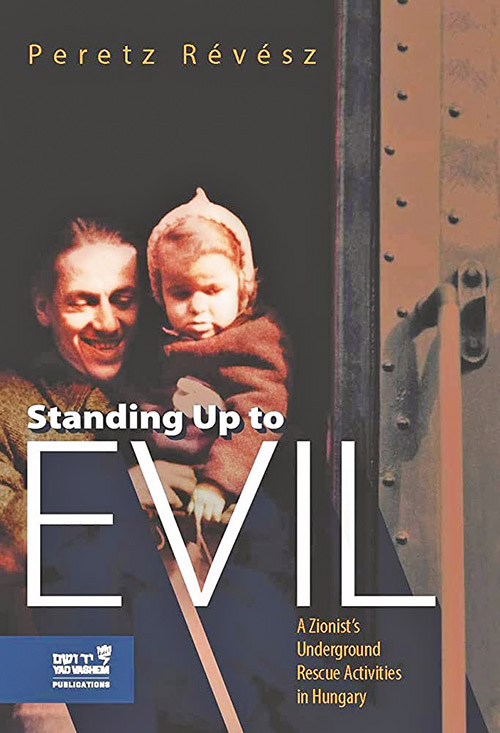

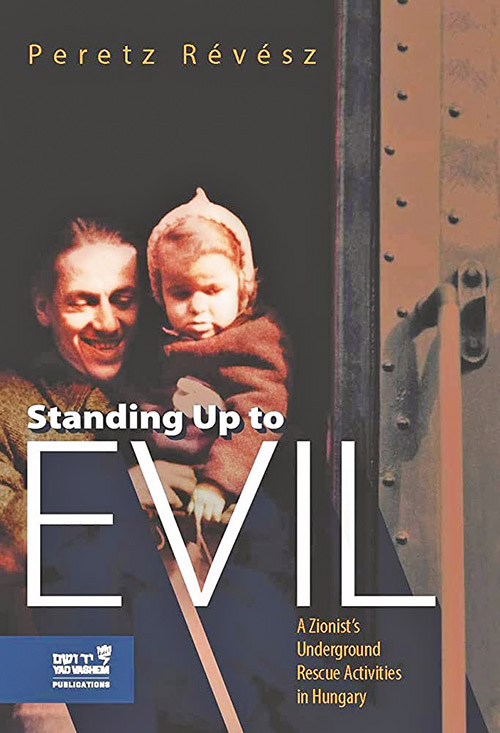

Highlighting: “Standing Up to Evil: A Zionist’s Underground Rescue Activities in Hungary” by Peretz Révész. Jerusalem: International Institute for Holocaust Research Yad Vashem Publications. 2019. ISBN-13: 978-965-308-582-4.

Between 1942 and 1945, most Slovak Jews were murdered either in Poland or in their national homeland, notes historian Yehuda Bauer. Brave and valiant efforts were made to save as many Jews as possible by the Bratislava Working Group, a unique Jewish underground organization. Gizi Fleischmann, a Zionist activist, led the group, with the aid of her relative Rabbi Michael Dov Ber Weissmandel and a number of Slovak Jews from divergent political and social groups. “The results were meager,” Bauer said, although they managed to save some Jews. A proto-fascist government in Hungary permitted Jews to leave the country, but rigorously limited the number. In 1941, many thousands were ousted from the country, ending up under German rule in the newly conquered Yugoslavia area, where they were murdered. Thousands more were drafted into forced labor battalions that were part of the Hungarian Army. Most perished in Soviet territories occupied by the Axis powers.

Background Under Which Budapest Zionist Rescue Organization Operated

The destruction of Hungarian Jews began in March 1944, when the Germans occupied Hungary. Four hundred thirty-seven thousand Jews were deported to Auschwitz. The Jews of Budapest and those who survived the forced labor camps, Bauer noted, were the only ones able to stay alive. The Germans aggressively pursued them in order to deport them to Auschwitz. The regime of Miklós Horthy was replaced after October 15, 1944 by the Arrow Cross, the far-right Hungarian ultranationalist party led by Ferenc Szálasi. Tens of thousands of Jews from Bucharest were forced on death marches to the Austrian border, during which many died. Hungarian fascists shot many others along the Danube River, while most Jews were driven into a ghettos, Bauer said, where they were murdered by the Arrow Cross or died of starvation. Foreign representatives including the Swiss, Swedish and others including the International Red Cross and the Vatican nuncio assisted Jews in finding places to protect them.

Armed Resistance in Slovakia

Armed resistance in Hungary was not feasible. In Slovakia, armed response became part of the strategy these movements employed in dealing with the existential threat, observed historian Robert Rozett, Yad Vashem’s academic editor for this book. He stated: “At the end of WWII, approximately half of the Jewish population of Budapest had survived the onslaught of Nazi occupation and the fierce fighting surrounding the Soviet conquest of the city—the largest rescue of a Jewish community in all of Europe. All this had taken place in just under a year—from March 1944 to February 1945—and while much of the credit for Jewish survival is given to the courageous efforts of neutral diplomats who used their prestigious positions to protect Jewish citizens, none of their efforts could have succeeded without the dedicated work of Jewish rescuers on the streets of Hungary’s capital.”

Peretz Révész

One key individual in this group was Peretz Révész, a refugee from Slovakia and a leader of the Maccabi Hazair Zionist youth group. Rozett said that when deportations from Slovakia began in March 1942, Zionist youth leaders decided to encourage Jews to flee to Hungary. Among those forced to escape to Budapest were Révész and his bride, Nonika, who arrived in April. There, he connected with local activists, and became a member of the Vaada L’Ezra Vehatsalah (the Relief and Rescue Committee), led by Otto Komoly and [Rezső] Israel Kasztner, that succeeded in aiding thousands of Jewish refugees.

Among other activities, Rozett said Révész was responsible for providing false documents to Jewish refugees. He also assisted Joel Brand, “who led the ‘Tiyul Committee’ to help Jews reach Hungary from Poland, aiding up to 2,000 refugees before the German occupation of Hungary on 19 March 1944.” He added that “… Jewish activists in Slovakia and Hungary displayed courage, ingenuity and great intensity as they engaged in a torturous struggle to rescue Jews from the hands of German, Slovakian and Hungarian perpetrators. Remarkably, Peretz Révész had a direct hand in many of these efforts, or was a close witness to these activities.”

Aside from providing a detailed account of how the Holocaust in Hungary unfolded, Révész sought to refute a number of “erroneous clichés” about the Rezső Israel Kastner trial, which he said raised a number of questions:

1. In 1944, were the Jews of Hungary aware of the magnitude of the Holocaust?

2. Was it possible for the Jews to resist the Germans or flee en masse?

3. Did the Relief and Rescue Committee and Rezső Israel Kasztner, one of its leaders, collaborate with the Nazis, and how do we define the term “collaboration”?

The trauma of the Kasztner trial in Israel and Kasztner’s subsequent murder is what moved Révész to write about his experiences. His personal involvement as an intermediary between Kastner and the underground movement “almost on a daily basis” enabled him to understand him and his motives. He was especially disturbed that “the outcry about the injustice done to him continues to this day.”

Dr. Alex Grobman is the senior resident scholar at the John C. Danforth Society, a member of the Council of Scholars for Peace in the Middle East and on the advisory board of the National Christian Leadership Conference of Israel (NCLCI). He has an MA and PhD in contemporary Jewish history from The Hebrew University of Jerusalem.