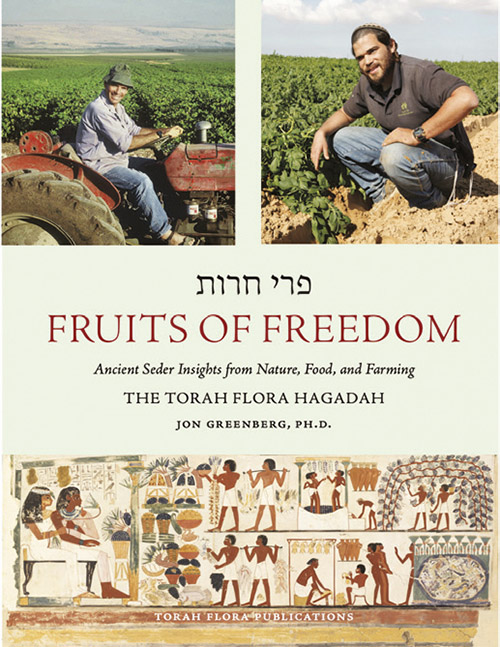

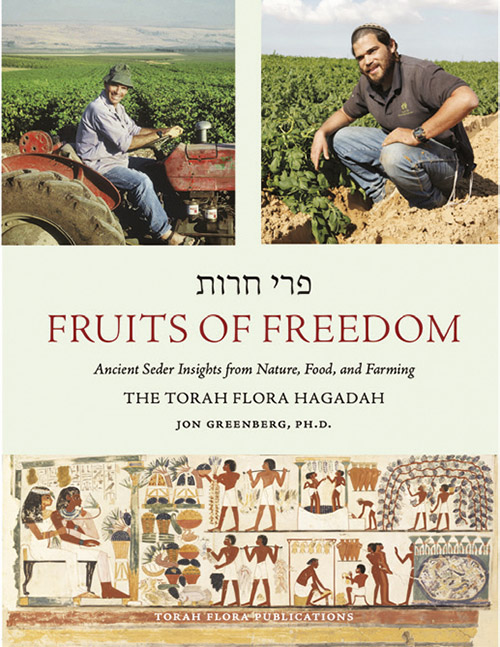

Reviewing: “Fruits of Freedom: The Torah Flora Hagadah,” By Jon Greenberg, Ph.D., TorahFlora Publications. 2021. ISBN-13: 978-1-09835-775-7.

It has been asserted that the Passover Seder (broadly defined as any kind of communal, festive meal, with or without the accompanying ritual and readings) is the most widely practiced ritual on the Jewish calendar, even surpassing shul attendance on Rosh Hashanah/Yom Kippur or candle-lighting on Chanukah.

Among the reasons offered for this are that the Seder’s underlying theme of cheirut, liberation and freedom, resonates well with contemporary concerns, and because the Seder is very much a DIY project, comfortably performed at home.

Central to any DIY project is a plan, a user’s guide, and the Seder is no exception: We call it the Haggadah, The Narrative (a term based on the terminology used in Shemot 13:8).

Given the ubiquity of Seder-celebration, it is hardly a surprise that the Haggadah is the most widely printed sefer in the Jewish canon. In 1997, bibliographer Isaac Yudlov, supplementing earlier efforts by Abraham Yaari and others, catalogued over 4,700 versions of the Haggadah. Today that number is considerably higher, with likely more than two haggadot for each year since the event it marks, Yetziat Mitzrayim, occurred. Each year dozens of new editions appear in sefarim stores and Amazon listings (not to mention those produced privately by individual families). Not all of these are traditional—many are decidedly not—but in reality there is but one Haggadah, recast thousands of times. Traditionalists may decry some of the more extreme efforts, their emphases eccentric, their interpretations (and interpolations!) radical, but each in its own way seeks to illuminate for its readers some aspect or another of their relationship to the Jewish people and its cultural history.

All of this is by way of introducing a new Haggadah, certainly traditional but with a decidedly unexpected twist.

“Fruits of Freedom: The Torah Flora Hagadah,” just released, is presented to us by Dr. Jon Greenberg, a longtime educator and educational consultant, who previously served as a senior editor of science textbooks for Prentice Hall. Dr. Greenberg (the doctorate is in agronomy) has dedicated years to the twin propositions that science and other areas of secular scholarship can aid and enrich Torah learning while, concomitantly, the insights of Chazal can sometimes shed light on science and history, as well. In particular, he asserts the belief that an appreciation of the natural and agricultural history of the world of Tanach and the Talmud can be determinative in reaching a clearer understanding of the Torah’s text and to unlocking rabbinic metaphors and homilies.

“Fruits of Freedom: The Torah Flora Hagadah” is formatted beautifully. Its Hebrew text and English translation are laid out on a single page, line by line, and it is accompanied by lavish illustrations throughout, most in full color. (Kudos to Barbara Greenberg, who provided some of these photographs, and to designer Misha Beletsky.) Clear instructions and a lucid general commentary are supplemented by Dr. Greenberg’s unique contribution to the genre: excursus (mostly brief) demonstrating how insights from the natural world and the history of food and agriculture can disclose unfamiliar meaning and nuance to various details we encounter at the Seder, including the ke’ara, the simanim, our menu, and the color of our wine.

Thus, Dr. Greenberg relates how some of the Talmud’s prescribed practices (e.g., the “karpas” course) developed into what we do today. The changing identity of marror is explored (in two separate comments) and the malleability of charoset is also examined. He offers us a look at some of the makkot, the divide between wine and beer in the ancient world, and relatedly, a cultural perspective on what lies behind the ban on chametz during Pesach. There is also a brief comment regarding the (Ashkenazi) ban on kitniyot, as well.

Rabban Gamliel’s exposition of the Korban Pesach leads to a consideration of how Second Temple-era Jews balanced the rabbinic proscription on raising goats and sheep within the borders of Eretz Yisrael with the need to maintain the sacrificial order and, pointedly, access to the thousands of sheep required for the Korban Pesach. The final bracha of the Haggadah is yet another opportunity to muse on the ecology of Eretz Yisrael.

Dr. Greenberg’s comments are not limited to the scientific. Two examples: He utilizes a lesser-known midrash to explain one of the more obscure references in the Haggadah, the prooftext cited from Yoel 3:3. In the final segment of the Haggadah, he considers the imagery in a line of text to present the reader with an illuminating look at opposites and paradox.

As is true of many Haggadah commentaries, some of Dr. Greenberg’s observations (e.g., on the suitability of oat matzah at the Seder, or his look at the disagreement

between Ben Zoma and the Sages and the [off-book] zoological allegory utilized there) may be better left for daytime perusal and discussion, lest one be led far afield on Seder night, but if your Seder includes participants apt to drift away for a bit anyway, these may serve to pique their interest and keep them at the table.

“Fruits of Freedom” was published this week. More information and a link to purchase can be found at http://www.torahflora.org/hagadah/

Myron Chaitovsky attended the Philadelphia Yeshiva and holds bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Yeshiva University and a JD from Fordham University. A longtime higher education professional, now retired, he is an independent scholar with an abiding interest in Jewish history and the Haggadah. He lives in Teaneck.