Each year, during the days and weeks leading up to Pesach, my social media feeds inevitably fill up with Ashkenazic laments about the custom to refrain from kitniyot and calls for “liberation” from this practice. Even the popularization of several moderate approaches to kitniyot has not stopped the clamoring for an end to it and even, in the case of some people, the jettisoning of this venerable custom.

Several factors contribute to this recent intolerance. For one thing, it is a reaction against increased stringency on the part of some rabbis and certification agencies. Peanuts began to be treated as kitniyot within living memory in some communities, and quinoa is undergoing a similar process now. For another, the rationale behind the forbidding of kitniyot is not clear.

Several different explanations appear in the earliest sources, from fear of admixture during the threshing process to fear of a stray grain stalk growing amongst kitniyot crops to the grain-like appearance of kitniyot. In the general perception, none of these rationales seems sufficient to further restrict an already limited Pesach menu.

Finally, in Israel especially, there is no longer any geographic separation between Ashkenazic and Sephardic communities. Ashkenazim today shop in supermarkets filled with products that are “Kosher for Passover—for those who eat kitniyot” and see observant and pious friends and neighbors munching corn and rice products during the holiday. Sephardim have no trouble distinguishing kitniyot from chametz, thus undermining whatever rationale for the kitniyot prohibition that one may choose.

I would like to propose a theory for the emergence of this custom in specifically Ashkenazic lands. Ashkenazic communities, and the custom of kitniyot, originated in the temperate regions of northern France and the Rhineland. The climate there differed from the Mediterranean climate in two key respects: its summers were far milder, and it rained all year around. Each of these elements produced a change in agricultural practices.

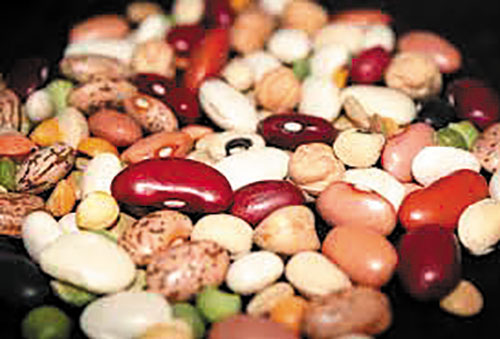

The milder summer meant that one could harvest twice each year, once in the winter and once in the summer, thus making the land more productive. Specifically, farmers implemented a three-field crop rotation. Each year, one third of the land would be planted with a grain in the autumn, one third with legumes (known for their soil-replenishing properties—and the technical meaning of the term “kitniyot”) like peas, lentils, or beans, in the spring, and one-third would lay fallow. When the same field is used to plant a type of grain one year and a type of legume the next year, there are inevitably stray stalks of grain growing amongst the kitniyot. Under the two-field system of the Mediterranean and Middle East, a field would be planted one year and left fallow the next. Thus, legumes were not planted as frequently and even if a particular field was changed from grain to legumes, there would be two years’ separation between the crops. The admixture of standing crops would have only been an issue in Ashkenazic lands.

A second difference pertains to the sheaving of harvested grain. In semiarid lands, crops were harvested in the early summer and gathered in the autumn, before the start of the rainy season. Thus, Shavu’ot, in the early summer, is a harvest festival, while Sukkot, in the early autumn, is a gathering festival. Because there was no rain expected during this interval, the harvested grain could be left in sheaves or heaps out in the field where they grew; there was no concern that rainfall would ruin them. This was not the case in Ashkenazic lands, where rain could fall any time throughout the year. There, special structures had to be built for grain storage near the fields. Since there was more than one harvest throughout the year, the same granaries were used for different crops—grains during one harvest and legumes during the next. Thus, the very structure where wheat had been heaped a few months earlier would be home to a heap of legumes just a few months later. Once again, this concern was completely absent in Sephardic lands.

Most likely, this explanation will not help those who crave lentil soup during the course of the holiday, and the gripes of Ashkenazim will surely continue. Nevertheless, this rationale demonstrates that the prohibition emerged from real concerns—the very concerns mentioned by the medieval rabbis—and should not be dismissed lightly. At the very least, during a holiday whose goal is to preserve historical and collective memory about our past, it is worth considering the circumstances that produced this custom and contemplating how we connect to a particular chapter of our past by observing this venerable practice.

Elli Fischer is a writer, translator, and editor from Modiin, Israel. He will be scholar-in-residence over Pesach on a riverboat touring the Danube. This article first appeared in the Intermountain Jewish News.

By Elli Fischer