Yotam was only 22 years old when he first made peace with death. It had only been a day since the October 7 massacre, and Yotam, an infantry member in the 931st battalion of the Nahal Brigade, had been called up to the northern front amidst fears of an invasion from Hezbollah. Dust swirled at his feet as he and his platoon entered the cramped military helicopter, flying low over the shoreline towards an unspecified forest about 10 kilometers from the Lebanon border.

From the helicopter Yotam could see the once-busy beaches of Israel empty and abandoned. “It was eerie and a strengthening experience at the same time,” he said. “You see a country that’s very clearly in horrible pain—a pain which we were still discovering the extent of.” He paused for a moment. “Just the beauty and stillness … and tremendousness of Israel’s cities as we flew on the coast. It was an unforgettable experience.”

When they arrived in the woods, Yotam didn’t know whether Hezbollah had attacked yet. In the end there never was any invasion, but the time he spent up there was some of the most terrifying of his life.

“No one wants to go into Lebanon,” he said. Yotam had relatives who served in the first and second Lebanon wars—his father being one of them. He knew the horror stories. The brutal terrain where enemies can be hiding anywhere and everywhere. Lebanon was a place where you could do everything right and still die.

Up north is where he found peace within himself. He had so many regrets, so many hopes and dreams. He had always wanted to be a father and start a family.

In the forest he let go of all of that. “I remember I was looking back on my whole life and I thought to myself, if I die, [at least] I die alongside my friends.”

After three days living in the woods, Yotam and his platoon separated from the rest of the battalion and headed south to complete their specialized auxiliary training. The next week was spent undergoing an accelerated training program.

His battalion commander had taken away all of their phones. He didn’t want the troops to lose morale. Soldiers in other battalions had seen the footage coming out of the October 7 massacre and it caused them to lose focus or in some cases even abandon the battalion.

There were only two times during those initial weeks that Yotam was able to use his phone. He used that time to reconnect with friends and family and reassure them that he was going to be OK. Other than that he was completely isolated from the rest of the world.

The days were long and arduous starting at 7:00 in the morning and lasting several hours past midnight. Those two weeks were spent preparing for the ground invasion. In some ways this was harder for Yotam than the invasion itself.

“We have a word for it, Ivada’ut—uncertainty.” The uncertainty, compounded by the isolation he felt, turned those two weeks into hell.

When the invasion was finally announced there was a sense of relief and satisfaction amongst the troops. Only once they boarded the buses to enter Gaza did the gravity of the situation truly weigh on them. Cheers turned to silence as they drove to a military base near Ashkelon that was being used as an entry point. From there the troops walked in formation through the dunes of Zikim towards Gaza. As bombs and mortars flew overhead they remained outside the security fence, which had not yet been repaired from the damage sustained on October 7, while awaiting further instructions.

At one point, a car pulled up right next to them and two middle-aged Israeli civilians popped out of the vehicle carrying pizza and soda for the soldiers. “Yossi,” one of the men said in Hebrew to his friend over video call. “Look what your pizza is doing.”

“It was so surreal,” Yotam recalled. Here he was in combat position, readying himself for battle, and two balding Israeli men were just handing out pizza as if he wasn’t about to go to war.

At around 3:30 a.m., they finally entered Gaza. The sounds of combat echoed in their ears as they walked through the farmlands of Northern Gaza, a constant reminder of the danger that lay ahead.

Dawn broke against fields of zucchini, onions and other produce surrounding the troops as they marched onwards. Yotam took a fresh fig off a branch and ate it. A relatively serene environment given the circumstances, but every so often the ground would shake from an explosion or a flash of light would overtake the horizon and the illusory peace would vanish.

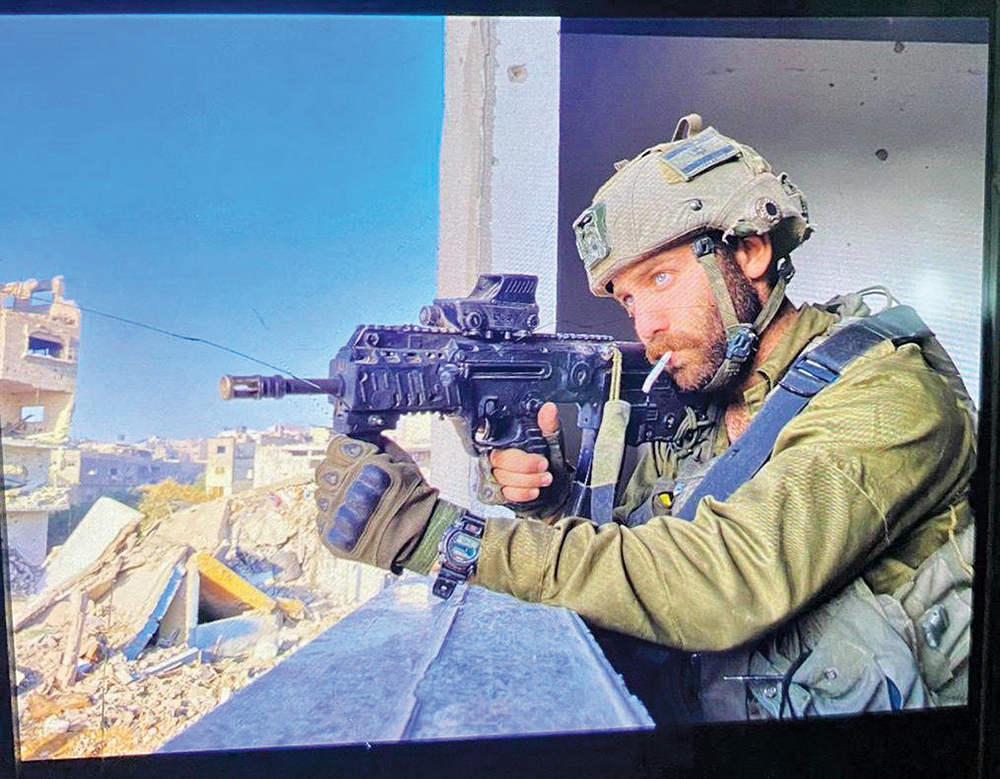

Nahal’s objective, as Yotam understood it, was “to find and destroy Hamas from a personnel and logistical perspective” and to take away “their ability to hurt the people of Israel.” Search and destroy was the mission and for Yotam’s platoon that meant systematically breaching buildings to find terrorists or terror-related supplies and destroying any infrastructure that could aid further terror attacks.

They would enter the homes either through the front door or an improvised side door created via explosives. From there they would methodically go room by room and floor by floor to make sure there were no militants hiding inside. Once the building was secure they would begin searching the home. No stone was left unturned as the troops tapped for hollow points, tore apart couches, and turned over drawers in search of weapons, tunnels and anything else that might pose a threat. Some days they would find uniforms of Islamic Jihad and Hamas or weapons—including, but not limited to, AK-47s, pistols, grenades, RPGs, rockets, mortars and ammunition. Other days they would find nothing at all.

Once they finished searching a house they would then set the interior ablaze—a necessary tactical precaution to prevent the enemy from later using it against them in battle. On some occasions, if the area was a point of focus, they would use the house as a temporary base of operations. One squadron would stay back to guard the house, while the rest of the platoon would leave behind their heavy packs and raid other buildings of interest in the area. At their most efficient, Yotam’s platoon searched through 10 houses in a single day.

Operations oscillated between hitkadmut (advances, usually towards the south) and peshitot (house raids or attacks) depending on the mission objective.

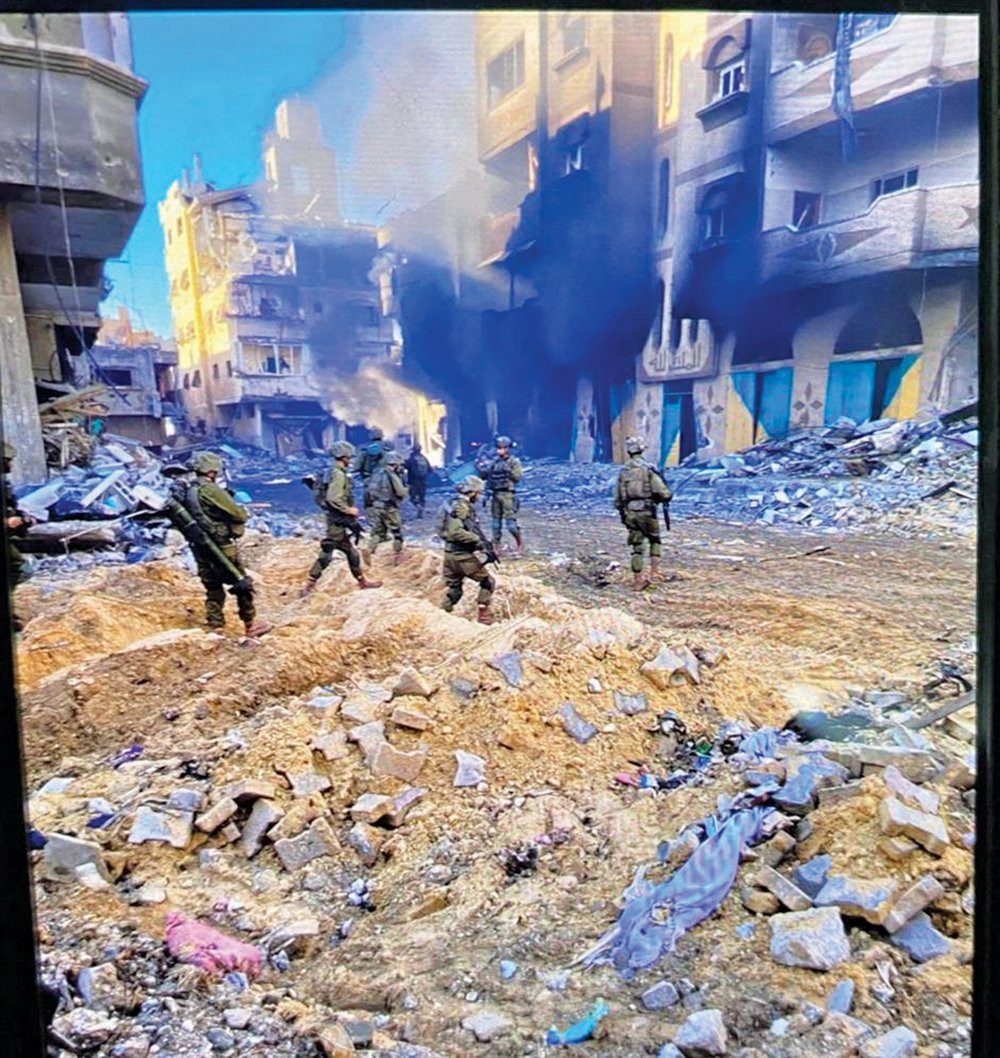

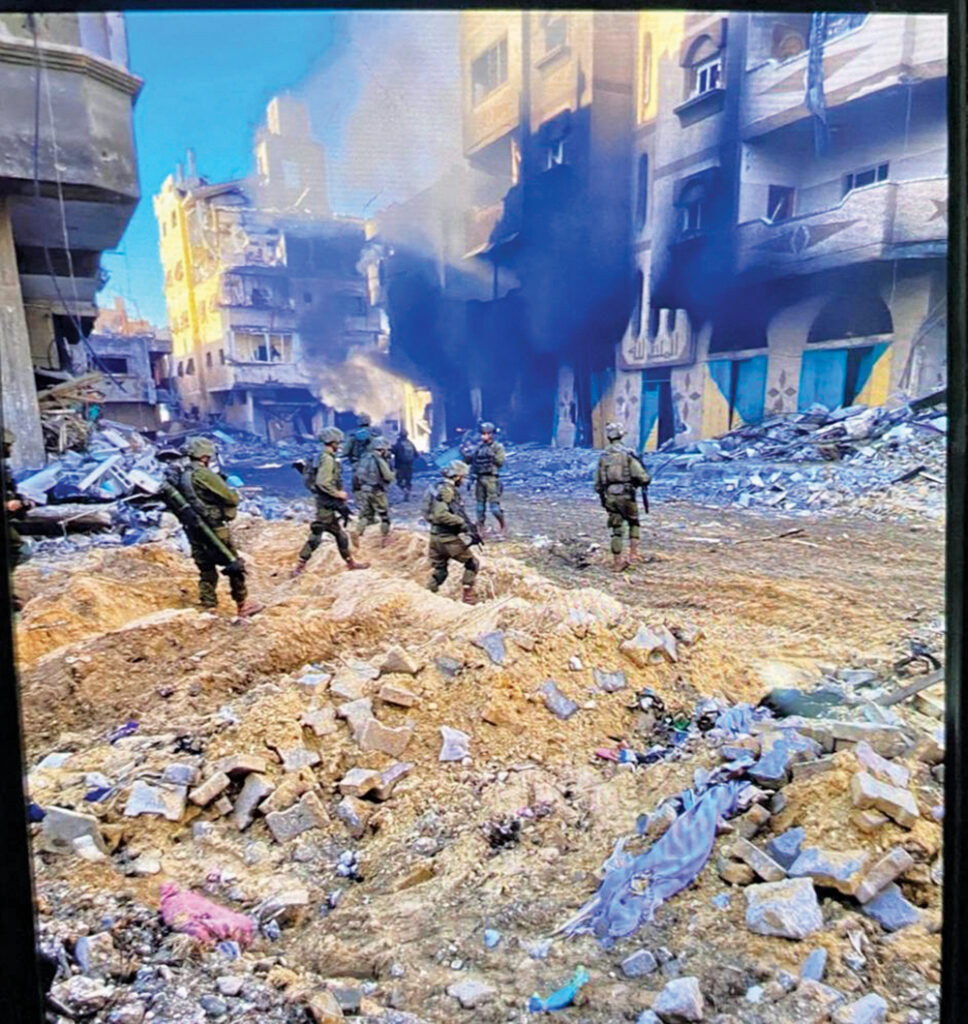

It was still early in the morning on that first day, around 7 a.m., when Yotam’s battalion arrived at the neighborhood of al-Atatra, an area of Beit Lahiya in Northern Gaza, which had long been considered by the IDF a political stronghold of Hamas. As the troops approached the combat zone they could hear tanks firing at targets they could not yet see. When Yotam finally entered the neighborhood, the scale of destruction was immense.

In preparation for the ground invasion, Northern Gaza had been bombarded with a nonstop barrage of airstrikes intending to cripple Hamas infrastructure as well as make the terrain more amenable for close-quarters urban combat. Almost every house Yotam saw was affected in some way. Some were completely destroyed while others had only blown-out windows. Despite witnessing the widespread damage firsthand, the scene did not seem real to him at first.

“We were watching some of these explosions happen 200 meters ahead of us. We watched the combat engineers blow buildings up right in front of us. We watched the tanks fire and the feeling was [surreal],” he explained. “Until we entered the houses themselves.”

Inside the houses, the soldiers got a glimpse into the lives of the Gazans who had lived there in relative quiet less than two months ago. The reality of their mission stared at them in every single home they searched.

Half-packed suitcases—abandoned when residents evacuated to Southern Gaza. Smiling family portraits watched as Yotam and his platoon ransacked their home. Paintings were ripped off the walls so the soldiers could see if there was anything hidden behind the frame. Wedding albums filled with happy couples and unique cultural traditions were put aside to look for weapons caches. Math textbooks and English homework were scattered about messy rooms. Before the war, people of all ages had been trying to learn English.

Another soldier explained how almost every one of the apartments they went into had an overabundance of extra mattresses and sheets, which he believed showcased the culture of hospitality the Gazan people embodied.

In the room of a college student, not much older than Yotam himself, he found a note in English on the wall: “Believe in yourself,” it read. One girl wrote in her diary about how she wanted to go to Paris. Hopes and dreams that may never come to be lived in these walls.

At the same time, in many of these exact homes they would also find weapons and Hamas or Islamic Jihad uniforms. People who cheered on or in some cases even participated in the atrocities committed on October 7. They lived within these walls, too. How homes of hospitality could house such inhumanity was a difficult thing for Yotam to digest.

“It’s not quite guilt. It’s uncanniness or disgust or being upset, but you never feel guilty,” Yotam stressed. “That doesn’t mean you’re enjoying it. It’s at times somber. It’s at times exhausting. Everywhere you go you smell smoke and dead bodies.”

The smell is something Yotam said he’s never going to forget. Gaza reeked of death—especially in the urban areas. He can still vividly recall the first time he came across it. Some members of his platoon had gone into a store looking for additional food and supplies. The store was filled with an assortment of goodies similar to the ones they had back home in Israel.

It was the first time they had come across soft drinks and treats since they entered Gaza. That excitement, however, would be short-lived.

“We enjoyed those snacks, but directly outside was this horrible smell. I looked and I saw a flock of sheep under the rubble,” Yotam told me. “I said, ‘That’s all right, it’s just sheep.’ As we continued deeper and deeper into the urban areas you would smell it more and more and more. From there it never ended.”

Early on in the operation two armed terrorists were killed by members of Yotam’s battalion. A bald man in his 40s wearing a Dri-Fit T-shirt and his friend in a red flannel shirt.

After a few days, Yotam and five other soldiers would come back to the area and find the two men still lying where they had left them.

The group approached the corpses and couldn’t help but feel a small sense of pride at having defeated an enemy who wanted them dead.

Yotam never saw the men’s faces.

Not long after that would he once more come face-to-face with death. The mission for that day was not the usual “search and destroy” house raids he had grown accustomed to during the war. The elite units in the brigade were set to overtake a terrorist outpost in the area while Yotam and his platoon would be covering the neighborhoods surrounding the outpost.

One squadron stayed behind to guard the supplies and temporary base of operations they had set up while the rest of the platoon left for combat.

During the battle, Yotam and some others found themselves running from cover to cover, desperate to avoid the volley of enemy ammunition headed their way. They sprinted down the large boulevard as an allied tank laid down suppressive fire, until they found temporary refuge against the side of a wall.

As they waited in cover, they cleaved tightly to the improvised barricade for protection.

Eyes darting back and forth.

Left. Right.

Left. Right.

That’s when he saw it—a bare foot protruding from a pile of dirt. The rest of the body was buried up to its shoulders underneath the mound.

The fighting lasted the entire day. It was a long and grueling battle, but eventually the IDF proved to be victorious and Yotam’s platoon returned back to the house to rest for the next day’s mission.

Those were the only three bodies Yotam had personally come across during his 27 days in Gaza, but in his heart he knew the stench of death didn’t only belong to the terrorists he fought. In Gaza, the dead smelled the same whether they were guilty or innocent.

“The only time I got a break from the smell was on the beach,” Yotam admitted.

During the early stages of the ground invasion, the beach in Northern Gaza had been taken over by Israeli forces and effectively transformed into a military outpost. After about a week and a half in combat, the beach offered a welcome reprieve from the miasmatic odor hanging over the rest of Gaza.

Yotam was in an uplifted mood walking past the cool ocean waves. In a video sent to loved ones he told them that he was safe and happy—explaining how honored he felt to be able to serve his country. Soldiers in the background of the video were seen shirtless taking in the sand or walking through the water. Others remained in uniform, but still relaxed. The warm atmosphere was a stark contrast to the macabre conditions of combat they had previously endured.

The fighting wasn’t just physically demanding, but it was psychologically strenuous as well. Prior to their arrival at the beach, Yotam’s platoon had advanced south from al-Atatra to al-Salatin, a small neighborhood located in the southwest of Beit Lahiya. Yotam made it to the entrance of al-Salatin while a battle was already in progress. One of the other platoons was taking RPG fire from the west while another platoon was advancing down south. Meanwhile, Yotam’s platoon was setting up a lookout point atop an abandoned three- to four-story preschool building, which he found to be slightly disquieting. It was very eerie to be conducting crucial military operations surrounded by tiny chairs, colorful numbers and childish drawings of cartoon characters.

Atop the lookout point, Yotam could see the whole field of battle. The platoon that had taken RPG fire was returning fire in the same direction. Another platoon was moving through an orchard below; all the while mortar fire arced over the entire plain.

From there, Yotam’s platoon pulled back and headed towards the place where they would be sleeping for the night.

That’s when they began to take mortar fire from the terrorists.

“They’re not particularly precise,” he explained. “But all it takes is one to hit you within the range of shrapnel and you’re dead.”

At that point there’s nothing you can do but pray. They couldn’t go back inside, so they pulled over to a nearby orchard for cover and waited for the shelling to stop.

While they were holed up, Yotam noticed something strange was happening to his body. One of his hands started to shake. Then his other hand began to shake. Soon his entire body began to shake uncontrollably.

“I realized that I was going into shock,” Yotam said.

He tried asking for help, but was having difficulty speaking and couldn’t quite articulate what was happening.

“It was terrifying,” he admitted. “You feel like you’re drifting away and losing control of your body, and it’s the last [place] where you want that to happen.”

One of his friends soon realized what was happening and followed the proper protocols to help him through the trauma response.

“Do you know who you are?” the friend asked. “Do you know what your name is? Do you know where you are? It’s all right. I’m here. It’s OK. Talk to me. Look at me.”

After spending about two hours in a state of shock Yotam eventually regained his senses and control over his body.

Not every situation was as intense as this one had been. Sometimes all it took was “two quick breaths” and he would get right back to work.

It was important to keep in good spirits and find the humor in their situation. It would have been impossible to remain somber for 27 days straight and maintain their sanity. Sometimes this would occur when looking through a house and seeing a picture or an item that they thought was funny; other times it would happen because of the absurdity of their environment.

One such bizarre occurrence happened when Yotam and his platoon conducted a standard house raid on the seaside villa of an Islamic Jihad member. The villa was gorgeous. It had multiple floors and clearly belonged to a well-respected man in Gaza. The walls were covered in awards and medals. As they were pulling uniforms and explosives out of the closet in one of the many bedrooms, Yotam noticed a “chicken on the bed sort of just hanging around.”

This somewhat-amusing event and familiar items helped relieve the stress of their day-to-day lives and functioned in a similar manner to the beach. A distraction from the misery and smell that surrounded him.

Yotam would return to the beach twice more during his time in Gaza. Once after a five-day mission to the al-Shati refugee camp and another after spending five to seven days in Jabaliya before he was sent back home.

These last two missions would be logistically some of the most complicated yet, due to the increased civilian presence in those neighborhoods. For weeks the Israeli government had been sending out leaflets in Arabic and messages over the radio instructing residents to evacuate to Southern Gaza. In the al-Shati refugee camp, Yotam personally watched as leaflets in Arabic from the Israeli government rained down from above.

Everyone who stayed had their reasons. Some were too stubborn to leave, while others were too scared.

In Jabaliya, one family cried and begged for their lives when they saw the platoon approach a neighbor’s home. A man in his 70s came out of the house followed by his wife, daughter and 2-year-old grandchild. Yotam’s platoon sat them outside, gave them some water, and told the family to be quiet while they assessed the situation. They needed to clear the family’s house now to make sure there were no terrorists inside. Even if the family were good people, it could have still been possible that Hamas was hiding inside and had threatened to kill them if they warned the soldiers. Yotam said he’ll never forget the look of shock on the little girl’s face.

“She was looking around and she didn’t understand what was happening,” he said. “Because why would she? She’s a baby.”

Yotam reiterated that he never felt any guilt during his time in Gaza, but at that moment he felt horrible that this was what it had come to.

Another time one of the other platoons came across another family that had stayed behind. They brought them outside to the courtyard and two people were with the family at all times for security purposes. The experience was far less tense than the previous one, since it didn’t occur during a mission.

This family was larger than the other one. There were two men about 50 years old and two women who appeared to be their wives. A little girl who couldn’t have been much older than 6 or 7, a boy only a few years older than that, a 2-year-old girl and their mother. One of the women suffered from dementia.

Yotam was told by his platoon members not to talk with the family whatsoever, but he didn’t listen. He always made a point of trying to make the children laugh. He would make silly faces and they would make silly faces back. He would come back and bring them sweets or a doll, anything to try and brighten their day given the dire conditions they were in.

He would later reminisce on those moments fondly, describing them as “the best” and “most pure” interactions he had.

On his last day of operations, one of the platoons heard a young man yelling while they were clearing a house. The man, they would soon find out, had participated in the October 7 massacres. They threw a grenade in the room to try and eliminate the threat, but unfortunately, the young man was not the only one in the room. An old man had a massive hole in his leg, an elderly woman got shrapnel in her eye, and a child was also lightly wounded. The terrorist meanwhile had received shrapnel to his head.

Yotam was in a different house when his friend ran in and told him that he needed Yotam’s lightweight portable stretcher. He quickly took the stretcher out of his pack and handed it to his friend.

An hour later his friend returned with the stretcher caked in dried blood. Yotam was later told that they had to sew the old man’s arm to his leg to stop the bleeding. He took the stretcher back, blood and all. He then folded it up and put it back in his pack. After fighting for so long he couldn’t bring himself to take the time to clean the blood off the hardened canvas.

Following this, the platoon spent the next two days back at the beach while waiting for the pause in fighting to go into effect.

The news of the pause brought a wave of relief over the troops. Not just because it meant the fighting would (at least temporarily) stop—they would have gladly continued fighting for their country if this pause wasn’t accepted—but because the conditions ensured the release of at least some of the hostages taken captive on October 7. The hostage release in particular was cause for much celebration among the troops. Perhaps more than anyone, these soldiers knew that Gaza was not a place for an Israeli civilian.

“It was an extremely satisfying feeling,” Yotam explained. To him this harkened the end: “Not of the end of the war, but of the beginning of the end.”

It meant a return to Israel—away from the smell and the bodies. It meant a return home.

One thing that stuck out to Yotam and his friends during their 27 days in Gaza was how otherwise normal the cities seemed to be. Across every economic strata, all the buildings were relatively modern, with relatively modern infrastructure inside.

They believed Gazans could live a lifestyle on par with any other nation, if leadership directed resources towards improving civilian infrastructure rather than lining their own pockets and funding terror.

While they admitted there would still have to be some sort of military presence or anti-terrorist control over the strip for security purposes—at least until a lasting peace could be established—from Yotam’s point of view the framework for a thriving society was already in place.

When I first spoke to Yotam during the pause in fighting, he was on base in “readiness mode” in case he had to be sent back into Gaza, although he was hopeful that wouldn’t be the case.

“If the hostages keep coming, I have trouble believing we’ll be going back to Gaza any time soon,” he optimistically opined.

Unfortunately, the pause would not last. On December 1, Yotam was called back into Gaza. We were able to briefly communicate before he left.

He told me that he was thankful for the six days he was able to spend in Israel, but now it was time to get back to work. He re-entered Gaza with a renewed confidence, far more prepared for war than he was when he entered the first time. He doesn’t know how he’ll react when he gets to the front lines, but he is not worried about facing the stench of death again. Yotam is now solely focused on the health and safety of himself, his friends and his country.

“Despite everything, I go back with a full heart. I’m even more motivated now to finish this, no matter how difficult, no matter how long it takes, no matter what it demands of us. This is our one and only home.”

David Deutsch is currently a sophomore at Yeshiva University, after spending two years learning in Israel.