In 1945, Jewish-American Army privates Robert Hilliard, 19, and Edward Herman, 25, Battle of the Bulge veterans, ran a covert campaign to aid Holocaust-displaced persons (DPs). Hilliard published an army newspaper. He and Herman were stationed at Kaufbeuren Air Force base, near St. Ottilien, a Benedictine monastery and former Nazi headquarters.

Survivor Dr. Zalman Grinberg converted St. Ottilien into a hospital for the gravely ill and sometimes for women giving birth. Doctors were healed first so they could heal others. With help from empathetic fellow soldiers and clergymen, Hilliard and Herman, risking court martial and disgrace, mobilized resources needed to save 750 DPs from hunger, disease, sexual assault and other abuses. Ironically, DPs’ “liberation” segued to mistreatment by the U.S. Army, but Hilliard and Herman were determined to eliminate that trauma.

April 1945: For approximately 50,000 Jews liberated from Austrian and German concentration camps, there was no returning home—either they had no surviving relatives or they feared harm from former neighbors. Malnourished and diseased DPs at St. Ottilien were dying daily, deprived of medicine and food; 60% were bedridden because they had nothing to wear, or only tattered striped pajamas or German/SS uniforms. DPs lacked blankets and bedding. Morris (2006) recounts how Eisenhower had ordered that “… all DPs get 1,200 calories a day, but most camps were serving more like 800, and many, virtually no food at all.”

May 1945: Five babies were already born into these conditions. Eventually, American troops framed the camp perimeter with barbed wire. One female survivor, repeatedly assaulted by Nazis and then again by U.S. military police (MPs) asked, “What’s the difference between you Americans and the Nazis, except that you don’t have gas chambers?” (Morris, 2006). A DP scrounging for food outside camp was shot by an MP and his leg was amputated. MPs disrupted a Yom Kippur service attended by GIs and survivors there, and beat survivors with rifles.

If these abuses were not enough, DPs faced Nazi-era attitudes about Jews as “parasites” feeding off German civilians. Pervasive antisemitism existed among U.S. military leadership and soldiers who more closely identified with German citizens than Nazism’s victims. General George S. Patton, a virulent antisemite, said: “If they [the Jewish DPs] were not kept under guard they would not stay in the camps, would spread over the country like locusts, and would eventually have to be rounded up after quite a few of them had been shot and quite a few Germans murdered and pillaged.”

Hilliard heard about St. Ottilien and traveled to see it firsthand. Shocked, he recruited Herman, a true businessman. Their approach was: 1) seek external help, but 2) given medical urgency and impending winter, cultivate an internal network to immediately aid the survivors. Among their diverse helpers were Chaplains Abraham Klausner and Claude Bond and “Dee” DiBiase, Hilliard’s assistant. Their ethically “gray” tactics bypassed military channels, as “extraordinary times call for extraordinary measures.”

Hilliard and Herman projected a rising death toll without immediate help. They took matters into their own hands, “requisitioning” potatoes and other kitchen food, but this was insufficient. The black market grew exponentially, and GIs raided kitchens to feed their mistresses.

Herman, a “macher,” bought the entire PX’s contents for $450 and commandeered Army trucks to deliver them to St. Ottilien. Hilliard, Herman and “accomplices” wrote a scathing letter about St. Ottilien’s conditions. They bribed a German to print hundreds of copies, which they mailed to family and friends, begging them to send supplies to Chaplain Bond. The men, assisted by Rabbi Klausner and others, searched for surviving family or relatives abroad to sponsor DPs’ departure to the U.S., British Palestine or elsewhere. Yet packages had not arrived after a month, and winter was approaching.

Herman’s brother Leonard distributed letters to prominent individuals. Perhaps courtesy of Senator Herbert Lehman, one reached President Harry S. Truman, who then sent Earl Harrison, University of Pennsylvania’s Law School dean, to investigate. Harrison stopped in New York to see Hilliard’s mother. She handed him her son’s letters, which established his credibility. Harrison reported back to Truman, whose subsequent reprimand to Eisenhower (aka Ike) appeared in Time and The New York Times. The Times (9/30/45) headlined Truman’s order to Ike: “END NEW ABUSE OF JEWS.”

September 1945: Eisenhower’s envoy arrived in St. Ottilien and ordered Hilliard and Herman to end their work, threatening them with deployment to remote locations—and worse. The men ignored the threats.

October 1945: Crates for DPs finally arrived. The letters’ recipients had generously responded but packages were impounded by MPs at New York’s docks. It was indeed a miracle for St. Ottilien that the donations eventually bypassed the military bureaucracy.

How could such treatment and appalling conditions for survivors at St. Ottilien and other area camps have existed? Some survivors even lived alongside Nazi sympathizers/persecutors and Jews whose cultures ridiculed other Jews. Later, approximately 200,000 survivors from the “East” (e.g., Auschwitz, Treblinka) also joined them.

For many American soldiers, “normalization” of relations with German civilians (especially women) fueled their underlying antisemitism. Survivors’ appearances seemed almost inhuman to them. This perception was reinforced by leaders, notably Patton, who eventually took charge of the DP camps. He said, “Harrison and his ilk believe that the Displaced Person is a human being, which he is not, and this applies particularly to Jews, who are lower than animals.” In addition, the U.S.’ need for Germany as an ally in fighting communism took precedence over aiding survivors and prosecuting Nazis.

Were U.S. soldiers in Germany monsters? No. More likely, they fit the motto “Never ascribe to malice that which is adequately explained by ignorance.” They had no preparation for, or knowledge of, survivors’ experiences or frames of reference. There was no “cultural competency” training, and little, if any, prior exposure to Jews. Does this excuse what happened in the camps? Certainly not.

Eventually the DP camps organized themselves. Grinberg became chairman of the Central Committee of Liberated Jews of Germany and Austria, and the last camp closed in 1959.

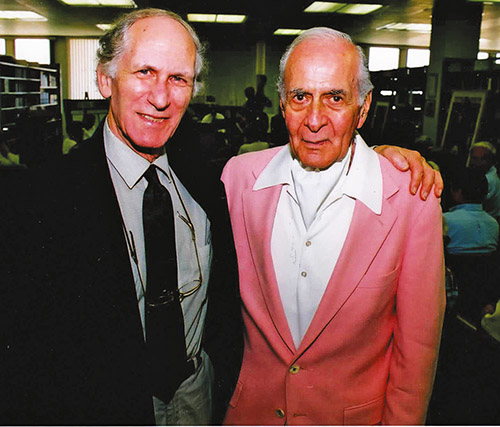

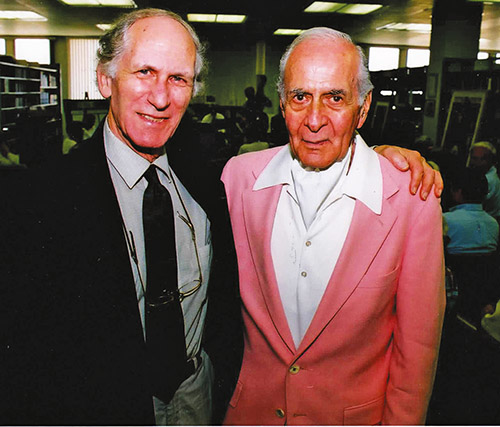

On May 1, 2000, in South Florida, the remaining survivors of St. Ottilien gathered for their first reunion, four years after Hilliard published “Surviving the Americans: The Continued Struggle of the Jews After Liberation.” In 2002, John Michalczyk’s documentary “Displaced: Miracle at St. Ottilien” was released.

Ed Herman passed in 2007. He was also credited with helping survivors get to then-British Palestine. Robert Hilliard, recipient of the Purple Heart, and a hero of St. Ottilien, retired from Boston University, but his support for global human rights is ongoing. Once widowed, he remarried at 92 and resides in Florida.

Rachel Kovacs is an adjunct associate professor of communication at CUNY, a PR professional, theater reviewer for offoffonline.com—and a Judaics teacher. She can be reached at mediahappenings@gmail.com.