On Bava Batra 55a, Rabba (bar Nachmani) relates a set of three teachings which Ukvan bar Nechemia, the Exilarch, told him in Shmuel’s name. The first, most famous one, is דִּינָא דְמַלְכוּתָא דִּינָא—“there’s halachic validity granted to the law of the land.” The second is that Persian sharecropping is up to 40 years (since a chazakah in Persia was after 40 years of use). The third is that there’s validity to a land sale by tax officials who sold it to pay the land tax. Presumably, the second and third are dependent upon the first teaching.

What do we know about Ukvan bar Nechemia, the Exilarch? At first glance, very little. His only other occurrence is in Shabbat 56b. There, Rav said: “There’s no greater baal teshuva than (King) Yoshiyahu in his generation, and there’s one in our (first Amoraic) generation. The gemara explains this is second-generation Rav Yirmeyah bar Abba I’s father, Abba; or alternatively, in another internal variant, Abba’s brother Acha.” Then, third-generation Amora, Rav Yosef said: “There’s another great baal teshuva in our generation, namely, ‘Ukvan bar Nechemia the Exilarch,’ also known as “Natan deTzutzita.”” Rav Yosef elaborated that once, he was dozing at a “pirka”—a lecture delivered on a festival, and saw in a dream that an angel stretched out his hands and received him (thus indicating that Natan’s repentance had been accepted).

I’d fix Ukvan bar Nechemia in the second and early third Amoraic generation. I assume that “mishum” indicates a direct communication from a relatively early Amora, Shmuel—rather than how some take it, as indicating an indirect tradition. I discussed this in greater detail in an earlier Jewish Link article, “On Behalf Of,” (September 1, 2022). He has to be contemporary enough to Rav Yosef to describe him (in Shabbat) as בְּדוֹרֵנו. Further, third-generation Rabba bar Nachmani cited him as an intermediate to Shmuel.

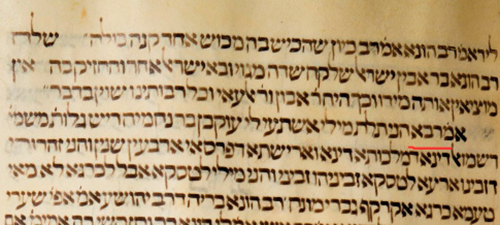

Now, Masoret HaShas notes that the girsa of the Rif and Rosh is that fourth-generation Rava—rather than Rabba—heard this report from Ukvan bar Nechemiah the Exilarch. It is Rabba in the Vilna, Venice and Pisaro printings, as well as the Florence 8-9, Oxford 369, and Vatican 115b manuscripts. However, the Hamburg 165, Munich 95, Paris 1337 and Escorial manuscripts all have Rava.

I can see the argument for Rava. After all, as the Gemara continues after the three laws cited ultimately from Shmuel. Then, fifth-generation Rav Huna bar Rav Yehoshua—who is Rava’s student—weighs in. Sixth-generation Rav Ashi discusses it further—noting others who argue—and cites someone who asked the scribes in Rava’s court, and only one manuscript, Oxford 369, has דבי רב, of the academy, instead. Still, I gravitate towards Rabba as Ukvan bar Nechemia’s quotes.

His Piety

Shabbat 56b doesn’t explicitly lay out his sin for which he repented. Rashi explains—citing a Sefer Aggadah—that Mar Ukvan had cast his eyes upon a married woman, and conquered his evil inclination. When he went out to the marketplace, a light was burning in his head. Thus, his name, “Natan deTzutzita.” This is also found, in short, in the Sheiltot on Vayeira. (I’m not so convinced, for I would imagine a major baal teshuva would have committed a severe sin, and then backed away from that path. It should be a big deal that the angel accepted his repentance, whereas in this story, it seems like he did not even commit the sin.) Rashi also writes that he was Natan Detzutzita because of the nitzotzot—sparks, which Rav Yosef observed in his dream when the angel accepted his repentance; alternatively, because of the tzitzit (fringes) of his head by which the angel seized him.

The specifics of his sin and repentance don’t seem to appear in Talmud Bavli. However, Rav Achai Gaon—in his Sheiltot on parshat Vayeira1—expands upon the story. Thus, he draws upon Sanhedrin 75a, דאמר רב יהודה אמר רב מעשה באדם אחד ונתן בן צוציתא שמיה שנתן עיניו באשה. Rav Yehuda quoted Rav, regarding a story of a man—and “Natan ben Tzutzita” was his name—who cast (natan) his eyes upon a woman. The woman was named Chana and he attempted to pay her a lot of money to be with him, but she did not accept. He literally became love-sick, and the doctors tried negotiating with the Sages what she could do to cure him. The Sages didn’t even allow her to even speak with him from behind a partition. Rabbi Yaakov bar Idi and Rabbi Shmuel bar Nachmani (both second-generation Israeli Amoraim) argued whether the woman was married or unmarried, but even if unmarried, later fifth-generation Amoraim explain why the Sages wouldn’t allow even this; the Talmudic narrator explains why Natan couldn’t simply marry her.

Our Sanhedrin sugya, doesn’t describe the offer of money, nor the identification of the man as Natan ben or deTzutzita (even in manuscripts I’ve seen), nor the woman as “Chana.” I’m assuming Rav Achai Gaon had such a text or oral tradition. Perhaps this was original to the sugya? Alternatively, perhaps there’s a closed-canon approach at play—just as occurs by midrashim about unknown biblical figures sometimes termed “the law of conservation” of biblical personalities. Applied here, we don’t want arbitrary unknown figures taking actions in Talmudic narratives, so we associate a name with the unknown person. As the saying goes, “and that young man … was Albert Einstein.”

Regnal Names

There’s some debate among sources and scholars in terms of grounding Mar Ukvan bar Nechemia. Did he live in Rabbi Akiva’s days? Shmuel’s? Rav Yosef’s? Is Mar Ukva the same as Ukvan bar Nechemia? Related to the Ukva/Ukvan and Shmuel versus Rav Yosef generation difficulty, some suggest that the statement in Shabbat of וְהַיְינוּ נָתָן דְּצוּצִיתָא is not meant to identify them as the same person, but to draw a piety/repentance parallel between two distinct people.

Seder Olam Zuta—which has numerous scribal errors in names and years—relates: “In the year 166 to the Temple’s destruction, the Exilarch was ‘Shechania;’ after him was his son Chizkeyah; after him was Natan Ukvan, he is Natan deTzutzita. Natan died and Rav Huna, his son reigned. … Nachum his son reigned, after which Yonatan, Shafat, Ana his son, Natan his son; Natan died and Nechemia his son arose; Nechemia died and Akavia (עקביה) arose—Rava and Rav Ada were his Sages; Mar Ukvan deTzutzita (the same עקביה) died and after him arose his brother Huna Mar—Abaye, Rava and Rav Yosef bar Chama were his Sages.”

In Toledot Tannaim vaAmoraim, Rav Aharon Hyman grapples with, analyzes and corrects this text. Recall that Rav Huna (Kamma) the Exilarch—distinct from the famous second-generation Amora Rav Huna—was in the Tanna Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi’s days, which would place Natan Ukvan/Natan deTzutzita in Rabbi Akiva’s days. Also, we should correct it so that Rabba and Rav Yosef appear earlier, and were Akavia/Mar Ukvan deTzutzita’s Sages, while Abaye and Rava, the Sages of Huna Mar.

As Rav Hyman explains, this resolves various difficulties and contradictions. As is common Jewish practice, the Exilarch family names sons after the names of parents and ancestors. (Indeed, consider the Shimon and Gamliel recurrence among the parallel office of Nasi.) Rav Yosef was saying that the great penitent in his own days was “Ukvan bar Nechemia”—by which name he was known when he was Exilarch—and Rav Yosef concludes that his true name was “Mar Natan Ukvan deTzutzita,” based on the name of his great-grandfather, who was also a penitent. The many aggadot regarding the attempted adultery and repentance described the actions of the great-grandfather.

I’m not entirely persuaded by Rav Hyman’s reconstruction. For instance, I’m not sure we need to massage the sources so that both Natan Ukvan deTzutzita Exilarchs sinned and repented. Instead, I’d suggest that, indeed, names recur. However, some of these names might be assumed upon ascension to the office of Exilarch.

Consider that many monarchs and popes assume a different name when beginning their rule, often echoing names of predecessors. Pope Benedict XVI was born “Joseph Alois Ratzinger.” The king of Assyria, Shalmaneser V, was possibly born as “Ululayu” (meaning born in the month of “Ulul,” what we call “Elul”). Similarly, Sargon II is assumed to be a solely regnal name. King Tzidkiyah’s name was originally “Mataniah.” Indeed, assuming an Exilarch name—one used by previous Exilarch ancestors—may lend authority to the new ruler. Therefore, I’d suggest that the penitent Exilarch in question, Ukvan bar Nechemia, indeed, was in Rabba and Rav Yosef’s generation, but “Natan deTzutzita” his regnal name—echoing the earlier ancestor.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.

1 See sefaria.org/Sheiltot_d’Rav_Achai_Gaon.42.1. Other midrashim detail a story at much greater length, and describe his means of pressure. Chana’s husband, a pauper, was imprisoned for his debts and Natan could give the money for his release. See bit.ly/3X5oXha.