How big is a kezayit, the olive measure used as a minimum size that is still considered halachic eating? There are well known positions both large and small. These are based on interpretations of Gemaras involving potential relationships between kebeitza and kezayit, and conversion from that volume measure to cubit and handbreadth measures. And where things don’t exactly work out, we might assert that reality changed, and olives, eggs or cubits grew or shrunk. Rabbi Dr. Natan Slifkin wrote an article, “The Evolution of the Olive,” discussing an interesting phenomenon. In lands where they had olives, the size of a kezayit was self-evident and didn’t require discussion, so the rabbis were silent. In lands where they typically did not have olives, Rishonim had to make educated guesses based on their interpretations of Talmudic texts, and these interpretations weren’t always right. Looking at such halachic literature, therefore, leads us to these larger sizes. Still, there are authorities that maintain that, at its core, a kezayit is really just the size of an olive.

Rav Herschel Schachter, in a recent shiur, noted that a kezayit is not really that big. Thus, even if a midsize kezayit is ½ or ⅓ a midsize egg, that’s fairly small. When he was a little boy, the eggs used to be smaller, and they also had large and jumbo eggs. Now, all the small eggs are used by the companies to make mayonnaise, so you won’t encounter a beitza beinonit (midsize egg) in the store.

Continuing on this theme, he notes that Rav Chaim Kanievsky married one of Rav Elyashiv’s daughters, and he arranged a shidduch for one of Rav Elyashiv’s granddaughters. When the shidduch went through, the groom went to Rav Chaim Kanievsky to thank him. In the books relating this story, they printed that he gave the groom four almonds to celebrate, told him to eat the four almonds, and then told him to say borei nefashot. The groom asked to have some more almonds and Rav Kanievsky said,“No! First say borei nefashot and then, if you want, you can have all you want. I want you to know that four almonds is enough for a kezayit.” The groom told Rav Schachter that it’s not true. He gave him three almonds! They were afraid to print the story with three because people would think it’s an exaggeration. People exaggerate nowadays how much a kezayit is, that you have to eat gigantic matzot and how many inches it has to be, which is a big exaggeration. I think mentioning “how many inches’’ represents a disagreement with the OU matzah chart, which I fuzzily recall him explicitly disagreeing with in the past.

Appearance Proving Identity

Admittedly, I’m discussing Pesach themes in the lead-up to the chag, but let us connect it with Daf Yomi anyway. In Bava Kamma 21b, in discussing the efficacy of unwitting despair (yeush shelo midaat) according to Abaye and Rava, a proof is brought from a Mishna in Maasrot, which mentions if a fig tree’s branch extends over a path and one found figs beneath it, it isn’t stealing to take them, but in the same scenario for carobs or olives, it is prohibited. The latter clause poses a problem for Rava, who says that unwitting despair works. Why should olives (or indeed carobs) be prohibited? Rav Abahu II, a seventh-generation Amora leading into the Savoraic period, explains that an olive is different, הוֹאִיל וְחָזוּתוֹ מוֹכִיחַ עָלָיו, since its appearance testifies to its owner. Then, the explanation continues, אַף עַל גַּב דְּנָתְרִין זֵיתֵי מִידָּע יְדִיעַ, דּוּכְתָּא דְּאִינִישׁ אִינִישׁ הוּא. “even though the olives fall off, the finder knows that the (olive tree / olives) in a place belong to that person.”(Thus, the owner wouldn’t despair even if he knew.) If so, shouldn’t the same be true for figs? Fifth-generation Rav Pappa (or Rav Pappi, or just the Gemara) explains that figs become disgusting when they fall.

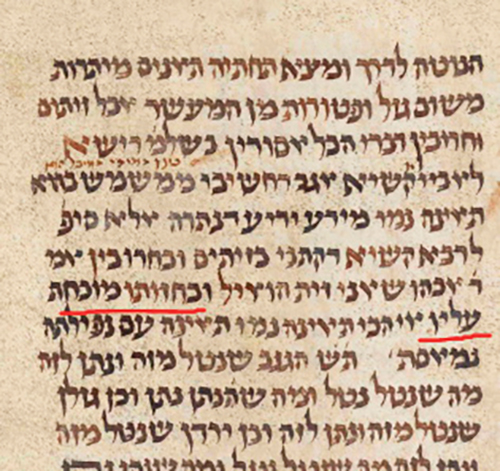

There are several “girsological” (relating to different manuscripts of the text) issues with this passage. First, the explanation that its location testifies to its ownership seems to run parallel to the appearance explanation. Indeed, the Florence 8-9, Hamburg 165, and Munich 95 manuscripts, as well as the CUL: T-S F 2(2).36 fragment, lack the explanation of its location working as evidence of its owner. Further, Rashi takes pains to explain what וְחָזוּתוֹ מוֹכִיחַ עָלָיו means – מראיתו ניכר של מי הוא הלכך מריה לכי ידע דנפיל לא מיאש – its appearance makes evident whose it is, and therefore its owner, when he knows it fell, won’t despair. This explanation, מראיתו, doesn’t fit with a location explanation.

Someone in the Rinat Daf Yomi chabura wondered aloud at this Rashi. Are individual olive crops really so distinct? It seems to me like this is an explanation arising from analyzing just the text, comparing חָזוּתוֹ for olives with נִמְאֶסֶת for figs, rather than something experientially-based, from familiarity with figs. This can be compared with various Rishonim in France and Germany who computed an olive size as corresponding to an egg, based on texts instead of direct experience.

Is Rashi’s shorter Talmudic reading compelling? I’d say so, under the principle of lectio brevior potior, the shorter reading is stronger, based on the theory that a scribe won’t deliberately omit phrases as he copies but might add explanatory text. Especially in Bava Metzia, we see many additions to Rav Yehuda’s Gaon’s commentary; this may be one such insertion. That doesn’t mean that the inserted commentary is incorrect. Indeed, I find it persuasive, as an explanation of the briefer text.

Tosafot, meanwhile, offer a compelling alternative. They note that a minority of manuscripts read שָׁאנֵי זַיִת הוֹאִיל וְזֵיתוֹ מוֹכִיחַ עָלָיו, an olive is different, since its olive (tree) proves it. This shorter reading again doesn’t require explanation of location because that is its plain sense. Proximity to the tree makes it clear whose olives they are. Then, a ח added to וְזֵיתוֹ changes the meaning, and counters the alternative of נִמְאֶסֶת. This explanation seems the most plausible to me.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.