It’s September 15, and I am at Brooklyn’s Polonsky Shakespeare Center, attending Remember This: The Lesson of Jan Karski. There’s a talkback session following the performance, and actor David Straithairn sits onstage. With him are director Derek Goldman and Clark Young, the playwrights. Oscar-nominated Straithairn’s masterful solo performance as Karski appears so exhausting that I marvel at his graciousness, and that of Goldman and Clark, all of whom field the audience’s questions. The session ends and I approach them regarding an interview. Strathairn is unavailable, but Goldman, Young, and I meet the following week on Zoom.

We unpack the play, film, and Karski, the complex man. These aren’t great starting points, though, unless one has Karski’s baseline biographical details. So here they are:

Snapshot of an

Under-the-Radar Hero

Jan Karski (born Kozielewski, in 1914) was born to working-class Catholics in Lodz, Poland and trained at university in law and diplomacy. At the outbreak of World War II, he fought in the Polish army, until its defeat. He was imprisoned by the Russians and then by the Germans; both interrogated and tortured him. Karski, an eyewitness to Polish Jewry’s destruction in both ghetto and concentration camp settings, crossed Europe at great personal risk, and pleaded with Allied leaders to intervene before Poland’s remaining Jews were murdered. After meeting Roosevelt, Karski returned to London, where his orders were to return to Washington as an unofficial representative of Poland. Karski married a renowned Polish Jewish dancer/survivor, taught at Georgetown University from 1949 until 1995 and in 1977, was interviewed by Claude Lanzmann for his documentary Shoah. Yad Vashem honored Karski in 1982. (See https://guides.library.georgetown.edu/c.php?g=1076777&p=7843909).

In Remember This, Goldman, Young, and Strathairn make Karski’s testimony and legacy accessible to audiences. How did Karski’s story become dramatized and from there, morph into a limited release film in 2022? What distinguishes the play from the film in execution and impact?

Backstory to the Genesis Of a Hero’s Odyssey

Although Goldman’s family links to the Holocaust are indirect, the subject has greatly influenced him since high school. In the 1990s, he created Right as Rain, a new play about Anne Frank, staged by a Chicago-based theater company as part of a three-year touring exhibit and museum, with support from the Holocaust Memorial Foundation of Illinois. Remember This would not have been possible, Goldman says, without this experience. He met dozens of Holocaust survivors in Skokie, Napierville, and other communities, which profoundly affected him.

The Holocaust re-emerged as an important focus of Goldman’s work when those planning the Centennial of the Georgetown University School of Foreign Service, where Goldman is Professor of Theater and Performance Studies and Director of the Laboratory for Global Performance and Politics. He was asked to dramatize Karski’s story. Goldman had not read Karski’s Story of a Secret State, but had some familiarity with his saga, as did Strathairn. Both had previously worked together. Strathairn felt Karski’s impact “in his gut.” Together with Young, his former Georgetown student and a current faculty member, Goldman co-wrote Remember This. The play morphed from an ensemble piece to Strathairn’s solo performance.

Karski’s Journey, Brought to Life Onstage and in Film

The play was workshopped and performed at Georgetown and other venues in November 2019. In January 2020, it was staged at London’s Queen Mary University for an International Holocaust Remembrance Day and 75th Auschwitz Liberation Anniversary commemoration.

The transition from play to film perplexes me. A relatively low-budget solo performance about a wartime hero may attract global audiences and be transferrable, but film’s barriers to entry are higher. Powerful studios love blockbusters but often reject financially risky, innovative scripts, so it’s harder for independent filmmakers to finance them. Goldman describes a “serendipitous” London encounter with Emmy-winning documentary-maker Eva Anisko. She suggested possibly filming the play, but scheduled festival performances precluded this—until COVID halted all performances. Goldman, Young and Strathairn then revisited Anisko’s proposal. The film was shot in six days during the pandemic. I explore how Karski’s story differs in the two media.

Film and Stage Convey the Same Story, but Differently

A camera permits audiences insight into Karski’s mind in a way that a play cannot. Jeff Hutchens, director of photography and the film’s co-director, captures Karski’s moment-to-moment experience with an intimacy that the communal space of theater can’t provide. “It’s less potent when 300 people occupy a theater,” says Goldman. Strathairn, filmed as Karski, is speaking directly to you. “Film,” Goldman shares, “is a private, psychic experience…right up in his eyes (with) more access to Karski’s interior experience.” The way film reveals Karski’s existential loneliness differs from theater, where a roomful of people bear witness.

The film captures a moment in time in the play’s development, which, in 2020, was still evolving. It’s been praised at festivals (see https://montclairfilm.org/events/remember-this/ for the next local screening), but the completed play meets the audience in the historical now. It begs the questions, “Why does this story matter today?” and “How must individuals grapple with their own sense of responsibility?” How did Karski deal with this?

How did Karski, the Man, Cope With That Trauma of What He Had Seen?

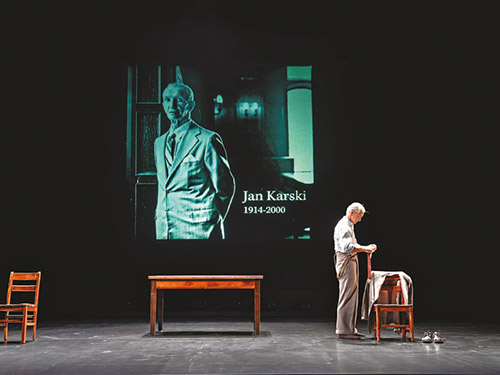

The play opens with Strathairn as Karski, on a nearly bare stage. A short video segment of Karski himself, about to begin his Shoah interview, is projected onto the backdrop. Karski sits, and then, abruptly, overcome with emotion, leaves the room. Eventually, he regains enough composure to tell Lanzmann his story. I am startled by the visceral intensity of Karski’s reaction.

Karski, a diplomat/spy/courier for the Polish Underground, and eyewitness to the Warsaw ghetto and concentration camp horrors, promised London-based Polish-Jewish refugee leader Szmul Zygielbojm that he would repeat these horrors to Western leaders. He did so, but how could he bottle such horrors up for years and still function well? Yes, it’s true that Karski wrote The Story of a Secret State (1944), but that account was more detached and less personal.

Young emphasizes that one must consider Karski’s long-term relationship with his wife Pola, a refugee/survivor, who also experienced great trauma. “Whatever the marriage was to them,” Young tells me, even “a silent communion…sharing your life with someone who knew—means that the relationship between Karski and Pola was one of the central pieces for him to be able to live with bearing witness and being haunted by that.”

What About Possible Discrepancies

In Karski’s Story?

Holocaust scholar Raul Hilberg and others point to possible discrepancies in Karski’s account, for example, whether camp guards were Ukranians or Estonians, or whether Karski was truly in Belzec or in Izbica-Lubelska, a Belzec secondary camp. These possible discrepancies don’t discredit his story. Young points out that during Karski’s emotional testimony for Shoah, after a silence of 35 years, it’s possible he made two simple mistakes that were held against him.

Goldman adds that in building a story, there are different versions of the narrative, and for legitimate reasons, this narrative comes under intense scrutiny. “When you make simple errors over 35 years, there are those who, in bad faith, want to …suggest that the rest is in question…it should be a subject for verification…in Karski’s story, there are agendas attached to it.” It’s interpreted differently in different parts of the world.

How Others Interpret and React to Karski’s Narrative—Do They Want It Toned Down?

Goldman and Young met with students at the University of Warsaw. In Poland, Karski’s story is not just a blank slate or one of heroism. It begs questions. Why did he not return to Poland until 1979? Was he considered a traitor? I wanted to know. Goldman and Young point to a genuine pride in Karski as a great Pole. “This story can be told in different ways with different emphases,” and perhaps the Polish might want Karski’s story “to go a little lighter on a texture of atrocities.” Karski did not get into Poles’ complicity, but it is a subtext and layer.

“Early in developing the play in Warsaw, we were getting input about the ‘heroic’ Karski, jumping off trains, doing valiant things, noble Karski.“ Those with whom they spoke wanted less emphasis on what Karski had witnessed and the suffering of the Jews. “That was one perspective…certainly not a holistic one,” says Goldman, but it “…comes up as a layer with people we meet, not just Poles.”

Both playwrights are determined not to editorialize in the play and to make Karski’s story, in Karski’s words, as accurate as possible, relatively free of agendas, “as it exists in the historical record.” Even though Karski spoke many times about his meeting with Roosevelt, he never editorialized on those occasions to blame Roosevelt. In the play, when he meets Roosevelt, “…people bring very different things to that scene and their sense of what they want to make out of it.”

Remember This: The Karski Legacy and Its Overall Impact

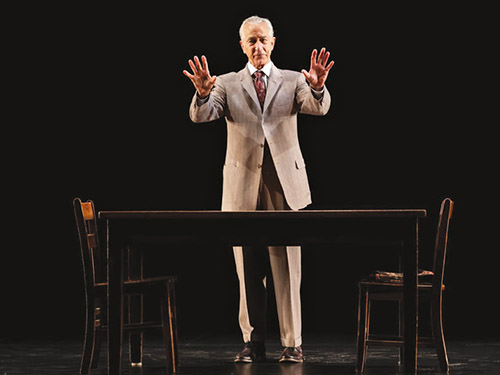

There is no question that the play, as constructed from Karski’s own words, and as Strathairn has flawlessly performed it, is immensely, breathtakingly, riveting. It is nearly incomprehensible how Strathairn convincingly represents prisoner and jailer, diplomat and supplicant, and any other roles that Karski relives onstage. Although he is palpably anguished at failing to accomplish Szmul Zygielbojm’s mission—to enlist Allied help in rescuing Polish Jewry—he transcends his harrowing war experiences. Instead of bitterness at the failures of leaders and institutions, Karski channels his energies into his students, who as individuals “have souls.” Strathairn, Goldman and Young deliver Karski to us with aplomb.

Goldman describes how gratifying it is that some people’s post-show feedback reveals that they “…have been so moved…they’ve known this story,” and that it has been “uplifted for others to grapple with.” For these people, “something…too little known… their experience of it being made visible now, in New York, by David (Strathairn)…” is part of something bigger, sentiments Goldman has never previously heard expressed in quite that way.

This extraordinary theatrical tribute to one man’s testimony, a man whose humanitarian odyssey met with skepticism and indifference, who retained and transmitted a legacy of humanity and decency, should be seen by all. Daily, in our fractured world, we witness senseless acts, perpetrated in hatred, against other cultures and individuals, and our own. Therefore, it’s critical that we remember and honor the memory of those, who like Jan Karski, altruistically, actively sought to end the persecution and destruction of others.

Rachel Kovacs is an Adjunct Associate Professor of communication at CUNY, a PR professional, theater reviewer for offoffonline.com—and a Judaics teacher. She trained in performance at Brandeis and Manchester Universities, Sharon Playhouse, and the American Academy of Dramatic Arts. She can be reached at [email protected].