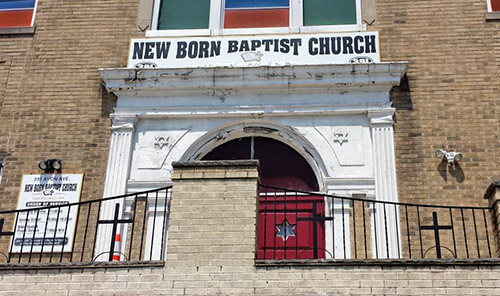

Driving down the streets of Newark you’d never know that this city was once a thriving Jewish metropolis. But just glance at some of the churches and you’ll notice a Magen Dovid carved into the doors, Jewish symbols in the ironwork and Hebrew letters still visibly etched into the stone façade of some of these historic buildings.

Before Jews left in droves for suburbs like Livingston, Millburn and West Orange in the 1950s and ’60s, Newark, New Jersey, was home to a proud and thriving Jewish community, with its first congregation (B’nai Jeshurun) established in 1848. To honor the community, and in celebrating Newark’s 350th anniversary in 2016, Congregation Ahavas Sholom, the oldest operating synagogue in Newark, is holding a retrospective, which tells the history of the community, its leaders and its many shuls. According to Phil Yourish, vice president of The Jewish Museum of New Jersey and curator of the exhibit, at its height in the 1950s there may have been as many as 60,000 Jews and 40 synagogues in Newark. But starting in the mid-’50s, Jews started leaving for the suburbs, with Oheb Shalom, the first major synagogue to leave Newark, moving to South Orange in 1958. Yourish estimates that by 1968 the remaining Jews had mostly all moved out.

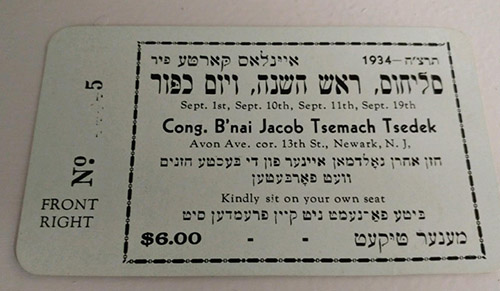

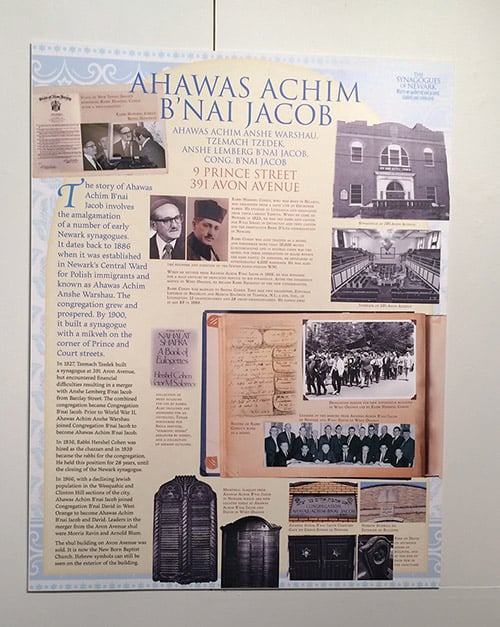

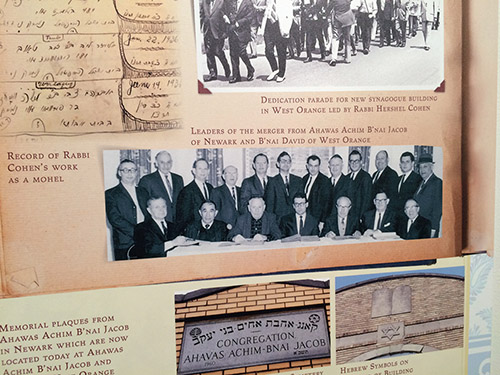

Although I haven’t spent much time in Newark, it’s a very familiar place to me, mostly through family lore. It’s the city where my father grew up, where he and his parents immigrated in 1951 from a displaced person camp in Germany after the Holocaust. My grandfather was the shammes of Ahawas Achim B’nai Jacob of Prince Street and then Avon Avenue, in Newark. He continued on as shammes after the shul moved to West Orange, where it is now known as Ahawas Achim B’nai Jacob & David. The shul was a perfect fit for my Polish-born grandfather as it had previously merged with a shul pioneered by Jews from Warsaw.

My father’s cousin, Rita Schuldiner, whose family came to Newark in 1949, remembers her neighborhood of Weequahic as “99 percent Jewish.” They lived right near the shul and the stores, and much of the industry in the neighborhood was Jewish. “In those days, everything was in the neighborhood,” she says, noting that she got married on the next block.

Harold Kravis, assistant gabbai at Ahavas Sholom, is extremely proud of both the museum and the shul, which continues to pull in a weekly minyan. Although his family left Newark for Hillside in 1968, when he was 12, Kravis has fond memories of his hometown. “It was wonderful living in Newark,” he recalls. It reminds him of modern-day Teaneck, what with the many butcher shops, bakeries and other kosher stores. His great-grandfather first came to Newark in 1903 and was the shammes of Ahawas Achim Anshe Warshau (the precursor to my own grandfather’s synagogue). Harold remembers Newark as a vibrant Jewish community—on “every corner in the Weequahic section, there was an Orthodox synagogue.”

Several synagogues are profiled in the exhibit at Ahavas Sholom, a shul once known as “the miracle of Broadway,” as it has survived since 1910, and one walks away with a deep understanding of the rich Jewish community that seems to have abruptly disbanded 50 years ago.

When Dr. Richard Gertler attended UMDNJ in Newark as a dental student in the 1980s, he realized that on his way to seeing a patient at the senior center in Irvington he had been passing by a Jewish cemetery. This opened up his eyes to the fact that “there was a Jewish footprint there,” and he began looking around the neighborhood and uncovering its Jewish past.

“Growing up in the suburbs, Newark was almost foreign territory,” Dr. Gertler says, but he soon discovered a growing interest in the city. Right across the street from Newark Beth Israel Medical Center was a public school that had formerly been the Young Israel (founded and led by Rabbi Zev Segal, father of JM in the AM’s Nachum Segal), which had housed the Hebrew Youth Institute (later renamed the Hebrew Youth Academy), the pre-cursor to Kushner Academy and the day school my father attended.

Newark itself is going through a resurgence as gentrification sweeps the city. And while, according to Yourish, “I don’t think [the Jewish community will] ever reach the heights of the first half of the 20th century,” once people start living in the downtown area of Newark, “I can see a Jewish presence once again.”

Even some of the Jewish industry is coming back—Manischewitz moved its company headquarters to Newark in 2011.

Several years ago, on a Thanksgiving morning (circa 2000) my father, Itch Zeidel, a”h, took Dr. Gertler on a tour of his hometown, revisiting all the old shuls, which for the most part had become churches. Dr. Gertler learned of the minyan at Ahavas Sholom (which is now Conservative, although it began as an Orthodox synagogue) and of the synagogue leaders’ plans for a museum. He was impressed by how proud they were of their shul, which celebrated the congregation’s first bar mitzvah after 25 years.

In addition to Ahavas Sholom, there is another remaining congregation from the early days of Newark: Mount Sinai in the Ivy Hills apartments, led by Rabbi Samuel Bogomilsky of Chabad since 1964, is made up of mostly Russian émigrés.

In Hillside, just a few blocks from Newark Beth Israel Medical Center, stood a shul that hadn’t been in use for a long time. But a couple of years ago, Dr. Gertler passed by and saw the lights on and a Shabbos lock affixed to the door. Inside were 30 black hats hanging on pegs. The men learning in this kollel were eager to show their guest the artifacts they had found—the old chazzan’s siddur and the memorial names on the sisterhood plaques.

“I can see a greater Jewish presence [in Newark] within the next 10 years,” Yourish says, as the city has been converting old buildings into apartment rentals and building new apartments, most notably right across from NJPAC. Yourish says people from New York and Brooklyn are beginning to see Newark as a viable place to live. With new apartments, retail spaces and even charter schools, there seems to be new hope for a Jewish community here as well. “We’ll see people living in the downtown area that we haven’t seen in years, if ever,” Yourish says, “except for the very early days.”

The Jewish Museum of New Jersey’s The Synagogues of Newark is running through February 15 at Congregation Ahavas Sholom at 145 Broadway. For visiting hours and more information, go to http://www.jewishmuseumnj.org/, email [email protected] or call 973-227-8854.

By Dassi Zeidel