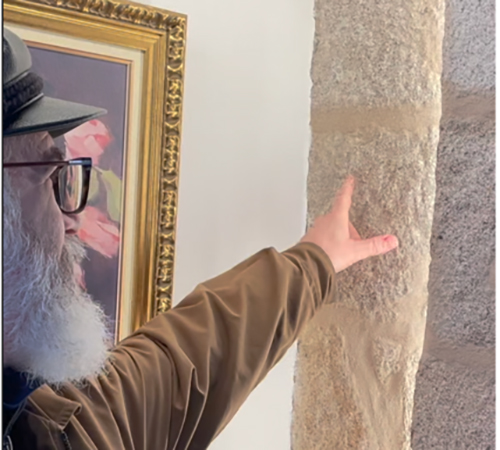

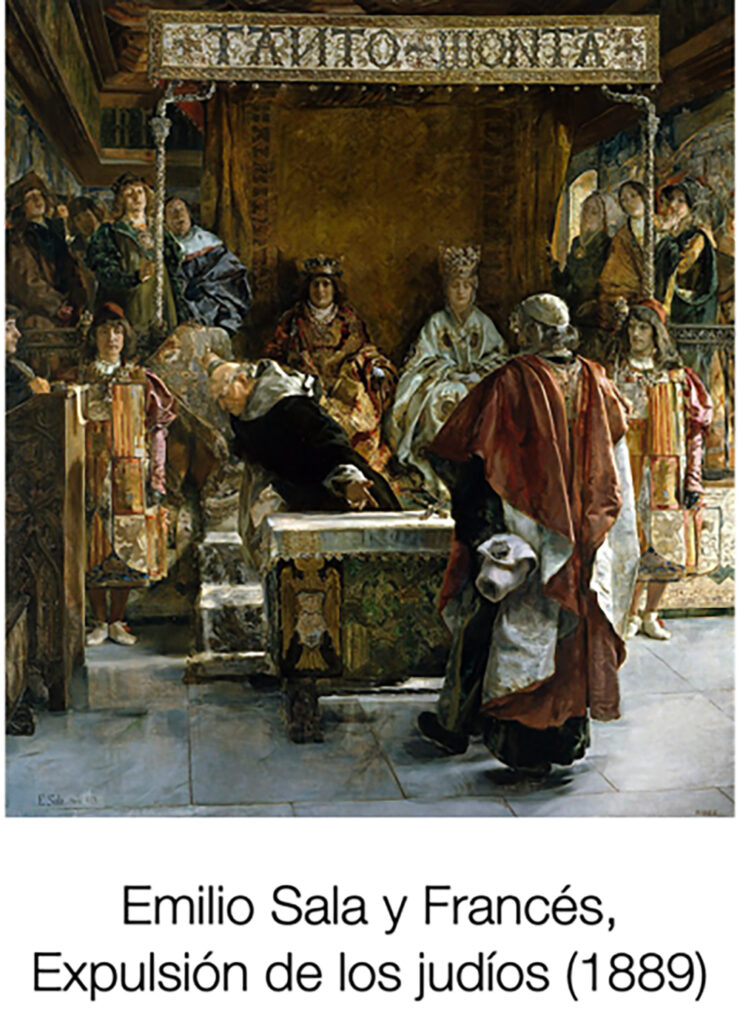

Mezuzah scars mark the doorways of hundreds, perhaps thousands of medieval doorways throughout northern Portugal, nestled in the villages that crown the rolling, terraced hills of the Douro River valley. Home to Jews for centuries, the region witnessed a great influx of refugees from the great expulsion from neighboring Spain in 1492. The Jews would only find themselves in still greater peril as the Portuguese King Manuel I engineered a forced mass conversion in 1497 (known as “the standing baptism”), and then shortly thereafter, the brutal Inquisition sought to extirpate any trace of Judaism from the Iberian Peninsula.

Denunciations, confessions under torture, and the infamous public burnings known as auto-da-fe terrorized generations of descendants of the Sefardim, sometimes known by the derogatory term marranos (“pigs”). Portugal would maintain discriminatory legislation and practices directed against the so-called “New Christians” until the later part of the 18th century. With no rabbis, no Hebrew texts or formal education, the religious life of thousands of crypto-Jewish families went fully underground for centuries.

When a crypto-Jewish community was first discovered in Belmonte in the early 20th century by a Polish-Jewish mining engineer named Samuel Schwartz, the residents were so isolated that they believed they were the last Jewish population to exist anywhere in the world. Schwartz was only able to convince them that Judaism had survived the Inquisition by reciting the Shema prayer in Hebrew to the village elder, who confirmed that he knew the name of God.

I recently returned from an advance site visit to northern Portugal with Kosher River Cruises, researching locations for our guests to visit this summer on our cruise exploring Jewish history along the gorgeous Douro River. Our itinerary covers the gamut of Portuguese history from its origins through the contemporary revival in Porto, but I was especially interested in visiting Trancoso, a tiny village of some 8,000 people that has been identified by archaeologists as a preserve of the largest concentration of crypto-Jewish inscriptions, some 250 of them scattered throughout the historic Jewish quarter. These inscriptions, featured in a local Cardozo Interpretation Center, are the Jewish equivalent of the Peruvian Nazca sand drawings: mysterious, tantalizing records of a hidden Jewish community. What, exactly, do they mean?

A handful of Portuguese scholars have developed theories to explain these strange inscriptions, noted since the 16th century. Perhaps the most convincing argument is that these complex engravings were used as a kind of code, intended to signal their presence to other crypto-Jews. The most common device is a type of modified cross, which seems to suggest that the crypto-Jewish family living in the home publicly proclaimed their New Christian identity—the safest message to project to those who might denounce them to the Inquisition—while tweaking the image somewhat, as if to communicate something subtly to a very specific audience. The typical placement of the inscriptions supports this theory: On the left-hand side of the doorway, opposite the doorpost where a mezuzah once graced a Jewish home.

It’s quite possible that these inscriptions also served a prophylactic purpose: Many of the homes of New Christians were defaced by ugly, crude crosses, and the more elegant, personalized designs might represent an attempt by the inhabitants to preserve a more aesthetically pleasing entrance to their home. One might think of the modified crosses as a type of public statement of religious fervor (genuine or otherwise), like the placement of an American flag on the front lawn to proclaim patriotism during the McCarthy Era. The flag would have particular significance if, say, the home was inhabited by people who sympathized with socialism and were afraid of public backlash. Needless to say, as awful as the McCarthy era was, the Portuguese Inquisition made that period of intolerance look like the cliquish ostracism of middle-schoolers.

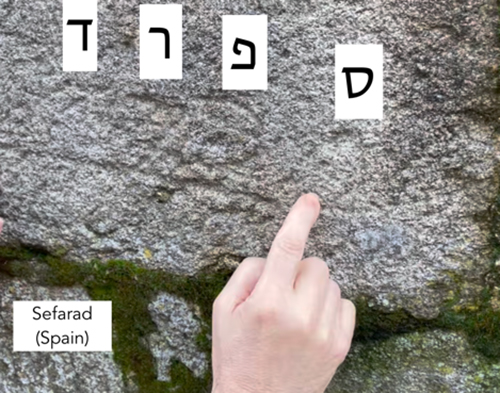

Perhaps the most tantalizing of the inscriptions, however, are those written in apparent Hebrew. One reads simply “Sefarad,” or “Spain.” Was this inscribed by a homesick Spanish Jewish refugee from 1492, choosing to memorialize his homeland in stone, possibly before the advent of the Portuguese Inquisition in the late 1530s?

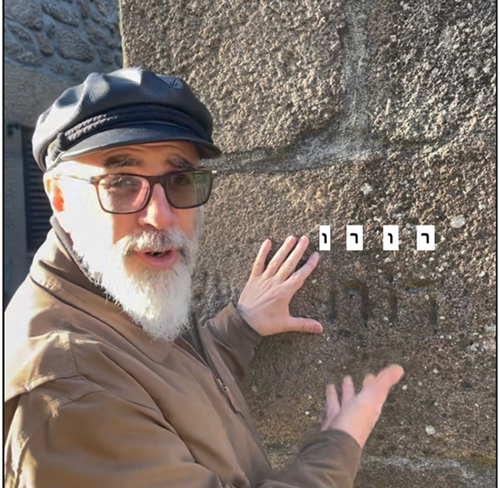

Even more puzzling are the dual “RORO” inscriptions on either side of a prominent home on a corner lot. The vowels over the vavs clearly suggest that the letters are meant to be read in Hebrew (and not as the number 1717), but RORO is a nonsense word in Hebrew. Some have argued that it might be read backwards, in a kind of kabbalistic at-bash formula, as an abbreviation for “OR-OR,” meaning “light-light,” but there seems to be little support for this contrived interpretation. The word might also be a Hebrew spelling of the nearby Douro River, the route that many of the exiled Spanish Jews took into Portugal, or perhaps a misspelling of the word ruach, or “spirit” (the apparent vowel patah under the second reish is not an inscription but a bit of lichen). More tempting, I think, is the possibility that this pseudo-word was inscribed by a partially illiterate crypto-Jew in a misguided attempt to record the Tetragrammaton, the four-letter Name of God.

These mysterious inscriptions speak to the incredible resilience of the Sephardic Jews despite the deeply hostile cultural climate of Inquisition-era Portugal. I look forward to examining these inscriptions again in May with Kosher River Cruises, traveling with a group of devoted Jewish history enthusiasts in our floating shtetl on the Douro River, featuring the amazing cuisine of Chef Malcolm and his protégé Chef Tobias, the inspirational minyanim and Torah learning directed by Rabbi Stuart Weiss, and the culinary adventures curated by Naomi Nachman. We look forward to spending our days exploring the Jewish past and our evenings in lectures and deep conversations with friends new and old.

For more information about the upcoming Douro River Cruise and their additional worldwide departures contact Kosher River Cruises at:

Web: https://kosherrivercruise.com

Email: info@kosherrivercruise.com

Tel: +1-310-237-0122

WhatsApp SMS: +1 (206) 536-3150

Israel: 052 836 2661

United Kingdom: 020 3393 6823

Henry Abramson is a historian who serves as a dean of Touro University in Brooklyn, New York. Since 2019 he has accompanied Kosher River Cruises exploring Jewish history along the waterways of Europe and the Caribbean.