By Chaim Goldberg

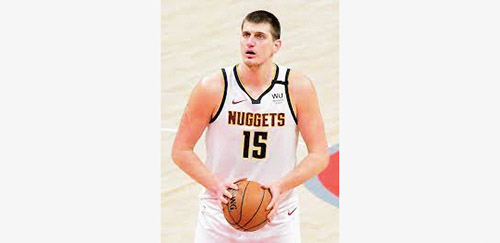

Leading up to the NBA Finals, Nikola Jokic’s selflessness, genuine humility and disdain of individual awards were already legendary. With his insistence that only a team accomplishment—a championship—would mean something to him, only one mystery remained: How would Jokic respond when the Denver Nuggets finally won a title? Despite knowing it would be out-of-the-box, there was zero chance of predicting Jokic’s unprecedented reaction to winning a championship.

Asked in his first postgame interview how it feels to be a NBA champion, Jokic laconically responded, “It’s good. It’s good. The job is done, now I can go home.”

Most $50 million celebrities who are feted and admired on a national stage will not openly regard their status as unimportant and equate themselves to the average working Joe. But here are Jokic’s own words postgame, “Nobody likes his job, or maybe they do. They’re lying.” And earlier in the finals: “Basketball is not the main thing in my life, and probably never [will] be. To be honest, I like it, because I have something more at home, family that is more important than basketball.” Jokic models a proper work-life perspective better than any celebrity around.

But if a picture is worth a thousand words, two photos capture his essence. One is Jokic standing next to the championship trophy with his little daughter Ognjena. All other players raise, caress and kiss the trophy. Jokic? He had his daughter use it as a toy, and then kissed and picked her up instead. Ognjena is his true trophy. When presented with the Finals MVP trophy by the NBA commissioner, he raised it up briefly to appease the throngs of photographers, then put it down and disappeared. Teammate Bruce Brown picked it up in disbelief and futilely looked for its rightful owner.

In the official team championship photo, Jokic leaves someone else to hold Jokic’s trophy front and center while Jokic quietly takes his place in the last spot of the back row, looking like a random team employee. Adorning him was not a championship T-shirt or hat, but Ognjena, goofily wearing his championship hat. Knowing these scenes make the following one less shocking. The next day, an ESPN interviewer noted in surprise that never before had an NBA Finals MVP winner showed up to her interview without the trophy. “Why not?” she probed. Jokic responded that it was lost. He put it, of all places, in the team equipment bag and didn’t see it there later. Believe it or not, the team’s equipment manager thought it deserved a more valuable safekeeping location than the bag containing knee socks and water bottles.

More significantly, while the national media has finally come around to recognizing Jokic’s humility and values, no one has written about the following: Jokic changed the definition of what a championship is. In Talmudic methodology, there is a distinction often drawn between the siman (lit. sign, indication) and siba (lit. core reason). For example, when we say that Shabbat ends with the emergence of three stars, is it that the core definition of how we mark nightfall is when three stars emerge (siba)? Or is the core definition of nightfall determined by a certain level of darkness, and the sighting of three stars is simply an indicator that it is now dark (siman)?

What is a championship? For most everyone, it is the siba. It is the core defining characteristic of who we decide to crown as the best team. It is the ultimate goal.

For almost everyone, but not for Jokic. When asked in the middle of the NBA Finals if it was the most important moment of his career, Jokic’s response was reminiscent of Rabbi Israel Salanter’s insight that one person’s physical needs are his fellow man’s spiritual obligation. “Yes,” Jokic declared, “because it might be the last chance to win a championship for Jeff Green, DeAndre Jordan and Ish Smith,” three Nuggets veterans who barely even played in the playoffs, but to whom a championship meant the world. “It’s maybe now or never,” for them, he said. Jokic didn’t care much for the accolades, but if it meant a lot to his teammates then it meant a lot to him.

In a postgame interview on the court, Jokic asserted, “We are not winning for ourselves, we are winning for the guy next to us, that’s why this is even more special. We believe in each other, the relationships that we have. Yes, trophies mean something, but it is our relationships that will go longer, even after we finish our careers.”

Asked about his penchant for passing, Jokic didn’t say a word about helping others score, which already would be a selfless mode of play. Instead, he offered a psychological lens, that passing is valuable because it helps everyone on the team feel involved and invested. His passing is a living example of the Mishna in Pirkei Avot, “Who is honorable? One who honors others.”

For Jokic, the relationships and bonds he has nurtured with his teammates and their families are more important than the trophy, than the championship. They are the core defining feature, the siba, of what makes the Nuggets the best team. The trophy is simply the siman, the reflection of what those championship level bonds can produce.

Chaim Goldberg has semicha from RIETS and is completing a graduate degree in child clinical psychology at Hebrew University. Originally from Denver, he now lives with his wife and children in Har Nof, Israel, where he teaches at various yeshivot and seminaries. He is a Rockower Award winner and has written for Jewish Action, Jewish Press, aish.com, YU Torah-to-Go and Intermountain Jewish News.