It’s Sunday, September 18, and a watershed event at the 92nd Street Y’s Unterberg Poetry Center. The Center’s Web site motto? “…where the community connects — through the voice of literature — to history…“

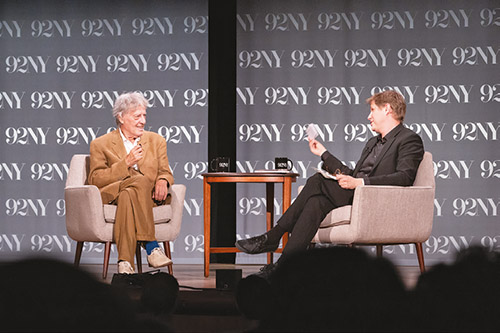

Undoubtedly, for the audience packing the auditorium, as well as for countless people attending online, the voice of literature is quite audible and accessible. Sir Tom Stoppard, whose Broadway hit Leopoldstadt follows on the heels of its successful West End run, converses with Daniel Kehlmann, a distinguished German-born author and son of a concentration camp survivor.

Kehlmann recalls how, years ago, Stoppard noted “the panic” in his eyes. That’s understandable, given the latter’s status, but they now sit comfortably as friends and colleagues. The tousled hair, tan-suit-clad playwright, screenwriter, and former journalist is poised and anything but forbidding.

Yes, tonight the Poetry Center is “…where the community connects — through the voice of literature…,” that of iconic Stoppard, perhaps the greatest living playwright. Yet rather than connecting to history, the men’s conversation focuses more on an absence of history in Stoppard’s work and life.

The Forgotten Family: Echoes of the Strausslers

Kehlmann’s conversation starter is Leopoldstadt’s original title, “A Family Album.” Leopoldstadt, Stoppard remarks, “…has a slight resonance in English with an English-speaking audience.” Yet “A Family Album” seems a more fitting title, given the play’s ironies. Even Grandma Emilia, the family matriarch, cannot identify those in the photos. “Here’s a couple waving goodbye from the train, but who are they? No idea. That’s why they’re waving goodbye. It’s like a second death, to lose your name in a family album.”

Those nameless relatives, one of the play’s metaphors for loss, also represent Stoppard’s own long-lost identity as Tomáš Sträussler, nicknamed Tomik, a self- described “bounced Czech.” His own Jewish roots, and his less-than-comfortable relationship with them, fit into an overarching theme in his writings of lost identity and lost history, “everything forgotten by later generations.” If Leopoldstadt is truly “all about forgetting what happened in a family,” as Kehlmann suggests, then Stoppard’s recurrent themes of unresolved loss and lost identity preclude neat endings, artistically and personally. The conversation segues to Stoppard’s works, notably Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead,” his first “mega-hit,” whose protagonists’ identity, history, and reasons for existence elude them.

Much of the focus here, though, is on Leopoldstadt, as per the Kehlmann—Stoppard interview, and insights drawn from the script’s cross-generational depictions of the Viennese Merz-Jakobovicz families. The characters’ attitudes about Jewish identity foreshadow the way their existence unravels over time. In Leopoldstadt, Jews’ dreams for acceptance in European Gentile society loom large.

Assimilation, Expectations of Acceptance, and Rude Awakenings

The assimilated, intermarried Viennese Merz-Jakobovicz families seek advancement and acceptance, like their “landsmen” in Europe’s cultural and economic capitals at the turn of the 20th century and thereafter. Many characters in Leopoldstadt avoid looking back. Once fully integrated into the Viennese middle and upper middle classes (or so they think), Kehlmann notes, “They don’t want to be confronted with their Eastern European past. They’ve cut off their connections to Ukraine and Poland.—at least they’re not going there…Also then, they are trying to live without history. For assimilated, bourgeois Jews, it was an embarrassment…’We’re not like those people.’”

Ironically, Kehlmann hits upon an historic but also contemporary reality for Jews. “Without antisemites, Jews probably would have disappeared from Central Europe by assimilation.” Although Judaism seems irrelevant to them, they are suddenly forced to confront it. According to Stoppard’s mother, in Zlin, the Jews reside downtown, wear all black, have long sidelocks, and are unlike more cosmopolitan, heavily intermarried families, such as her own. Regarding this, Stoppard notes: “Hitler made her Jewish in 1939.”

Hermann Merz and Ludwig Jakobowicz, brothers in law, argue about antisemitism, Herzl, Freud, and assimilation. Ludwig, whose career in mathematics has been stymied by antisemitism, maintains that Jewish converts to Christianity will still be considered Jews. To Ludwig, assimilation doesn’t mean to stop being a Jew, but “… to carry on being a Jew without insult.” Hermann mocks Herzl’s call for a Jewish state and deludes himself that his economic status, conversion to Catholicism, and Gentile friends’ support will permit him membership in the Jockey Club.

Casualties of the Holocaust and the Absence of Collective Memory

The Holocaust’s near annihilation of the Merz-Jakobovicz families is compounded by the attitude and “amnesia” of Cousin Leo (renamed Leonard), the sole great-grandson to escape Nazism. He, his mother, and English stepfather, whose name (Chamberlain) he adopts, flee Vienna. Kehlmann quotes Nathan, Leo’s DP/survivor cousin, “…you live as if without history, as if you throw no shadow behind you.”

Leo’s newly English “charmed life” and blissful ignorance of his family’s destruction parallel Stoppard’s own thinly veiled history, Kehlmann suggests. Stoppard’s rejoinder is “In my case, it wasn’t in my mind, and I forgot about them.”

Stoppard fortuitously escapes both the Nazis in Czechoslovakia via the family’s move to Singapore and the Japanese invasion there. Mother and sons flee to India; his father’s death on a torpedoed ship is confirmed. Subsequently, his mother remarries a British officer and Stoppard arrives in England at age eight. He morphs into a cricket-loving schoolboy. His mother skirts questions about her Jewishness; add to that Stoppard’s self-described “culpable lack of curiosity” and “lapse of character.” Thus, his search for Czech family and Zlin, his Moravian birthplace, transpires only decades later. “In my case, I just did not look back.”

Although Stoppard’s lack of interest partially explains his decision not to explore his Czech roots, he tells Kehlmann another reason that his mother “never really went there”— a legitimate fear that in communist Czechoslovakia, anyone with relatives in the West could fall under suspicion. He eventually visits his Czechoslovakian birthplace, supports dissidents like Vaclav Havel, and bases his play Rock and Roll on realities of that time. As an anti-Soviet activist, he rallies and raises funds for Soviet Jews and political prisoners. His artistic decisions, like his political ones, have always been works in progress.

The Theater as a Living Organism; What Begins Like Checkhov Becomes Jewish Vienna

Stoppard’s comments to Kehlmann about Leopoldstadt’s script changes (including the family album, a later addition) suggest why it continues to evolve: “Theatre for me is this organism…I’ve always insisted that theatre is an event, not a text.” He attends rehearsals and participates in casting. “This…is “Leopoldstadt #3…there are differences…the creative imagination is a strange thing.” He references his “lack of self-awareness,” such that in Leopoldstadt, he didn’t anticipate that a certain relationship would occur until he completed the previous scene. “It may sound “mechanistic,” he says, but he’s thinking, “What can I do that the audience doesn’t expect, so I do it…I’m hostage to a regular surprise effect”.

Stoppard admires Chekhov, and Leopoldstadt in part, resembles a Chekhovian play—except for a predominance of Jews. Stoppard and Kehlmann pivot to Leopoldstadt’s opening scene. It’s 1899. The children, all agog, decorate the Christmas tree. Jacob Merz, Hermann’s son, places a Magen David atop it. His mother indicates that it’s the wrong star, but apart from that, it could well be Chekhov As Kehlmann suggests and Stoppard confirms, the play starts as Chekhovian and then works its way into Stoppard’s unique creation. The star on the tree is a metaphor for Stoppard’s life.

Stoppard Wrestles with His Jewish Past—and Present—Or Does He?

Leopoldstadt may well be Stoppard’s capstone work. Director Patrick Marber has orchestrated an artistically and technically flawless creation. It could be the story of myriad Jewish families who contributed to the cultures, medical/scientific advancement, and economies of European countries and then were abruptly robbed and booted from those nations they faithfully served.

The final scene, set in 1955, is perhaps the most telling. Nathan returns to Vienna from the DP camps. Rosa, his Upper East Side psychotherapist aunt, has come to repossess the family apartment that the Nazis confiscated. Leo meets them there, and after he basks in the glory of his Englishness, Rosa shows him the family tree. As Leo reads out the family names, one by one, Rosa identifies their place of death. However shocking the impact of these revelations is for Leo-and it is– it is anyone’s guess as to whether, and how, this knowledge changes him long term.

It’s clear, from Stoppard’s own words, and Kehlmann’s inferences, that Leo in many ways reflects Stoppard himself. In midlife, he seeks to discover what really happened to the Czech Strausslers and Becks of his past and that which his mother never answered for him. As with Leo/Leonard Chamberlain, how deeply that knowledge affects him is also anyone’s guess.

And Now What, Tomik Sträussler?

Kehlmann’s insightful probing of Stoppard’s life stops short of asking why, in the nearly 30 years since he confirmed his Jewishness and his family’s deaths in the Shoah, Stoppard hasn’t taken steps to find out what, if anything, being Jewish means for him—other than in the context of history. It’s not hard to understand his affinity for his “charmed” English life or for seeking information about his birthplace, his father’s death, and “lost” family.

Nevertheless, one senses Stoppard’s discomfort with his Jewish identity, and an absence of questions that might clarify this. Among my own friends and acquaintances, there are those who seek a more active, spiritual connection to Judaism. Others distance themselves from Jewish observance and even question G-d’s existence. In both cases, they explore Judaism’s place in their lives. In either context, their decisions are respected because they are not taken lightly.

At the risk of appearing a critical rather than an objective observer, it seems remarkable that this genius wordsmith has not embarked on such a quest. At nearly 85, in the sunset of life, one might think Judaism would interest him. “A lack of character” on Stoppard’s part is dubious. The “lack of interest,” which postpones both an investigation of his Jewish background (until age 55) and precludes a deeper search as to what being Jewish means, is perplexing. Why lack such interest when things for Jews are cycling in a direction that Stoppard’s ancestors experienced, one of anti-Jewish tropes and out and out antisemitic violence?

None of this detracts from the superlative artistry of Leopoldstadt or the exceptionally insightful conversation with Kehlmann. It’s merely an observation about a curious disconnect, seemingly unexplored and unresolved, in Stoppard/Sträussler’s complex life.

According to Lee (2020), Stoppard’s son Barny gave him a birthday card that read, “’May the force be with you.’ I think it often is.” In the spirit of Mel Brooks, whom Stoppard identifies as one of his early influencers, it would probably be more apropos to say, “May the Schwartz be with you.” Tomik Sträussler, good luck on your cosmic journey.

Rachel Kovacs is an Adjunct Associate Professor of communication at CUNY, a PR professional, theater reviewer for offoffonline.com—and a Judaics teacher. She trained in performance at Brandeis and Manchester Universities, Sharon Playhouse, and the American Academy of Dramatic Arts. She can be reached at mediahappenings@gmail.com.