Sheremetyevo Airport, Moscow, December 1979. Across the airfield, Russian bombers are taking off, beginning the invasion of Afghanistan. Here on the civilian side, I’m sitting with my college classmates, waiting for a night flight from Moscow to Kiev.

Suddenly one of my friends nudges me. He motions to an older gentleman with a black hat and a long, gray beard.

I have just become observant, having gotten chopped or “converted” at Ohr Samayach in Jerusalem four months earlier. Back at my secular New England college for senior year, I was suddenly the only student on campus wearing a kippah. So everybody in my world knew that I was moving toward Orthodoxy.

We had been in Moscow for a week already on a student tour, with upcoming stops in Kiev, Leningrad and several smaller cities. This older gentleman was the first person any of us had seen who publicly identified Jewishly in what was still a Communist regime merciless to Jews.

If you applied to emigrate to Israel or the United States, you were immediately fired from your job and branded a criminal. In the Soviet Union, the so-called workers’ paradise, it was illegal to be out of work. Hence, Jews who sought to leave the Soviet Union were dubbed refuseniks.

I had no intention of approaching the rabbi, because I figured that a Russian Jew having unauthorized contact with an American would only get him in serious trouble. We were on the same flight, but I didn’t even make eye contact. I had already laid tefillin on the Aeroflot flight from JFK to Moscow. I figured it wouldn’t do any good to call any further attention to myself, either. Not if I wanted to go home on time.

That Saturday morning, in Kiev, I skipped the planned day of sightseeing, itself a risky move, and made my way through darkened streets, on which elderly Russian women were sweeping away fresh snow. I had memorized the route from my hotel to what I hoped was a working synagogue. It was shocking when I reached my destination, saw a concrete Jewish star out front, and realized that Shacharit services were about to begin.

The place was packed with old men, although when you are 20, I guess everyone looks old. Most wore white shirts that looked pretty ragged. The ones wearing new shirts could afford them because they were informers, I later learned. The services went along, no different from Ashkenaz morning services anywhere in the world. Since I was a stranger, they called me up for an aliyah. And while I was saying the brachot over the Torah scroll, guess who emerged from a side door on the bimah?

The rabbi from the Moscow airport.

It turned out that it was Rabbi Pinchas Teitz, zt”l, an American rabbi from Elizabeth, New Jersey, known for his work supporting Russian Jewry.

They used to tell a story about Rabbi Teitz that when he came to Russia, he would bring 14 pairs of tefillin with him, to distribute to needy Jews. If asked for an explanation by a Soviet customs agent, he would explain that he needed one pair for every day.

And so did his wife.

After services, Rabbi Teitz brought me back to his hotel room, where we had a modest Shabbat lunch, after the crackers and sardines the synagogue served at a kiddush after davening. I told him my story, that I had only been observant for four months, and that I was traveling with a student group.

He told me that there was an underground group of refuseniks in Moscow. If I wanted to make contact with them, I should call from a public pay phone on the street when I returned to the capital. I should not call them from my hotel room. If I did so, I could join them for a Shabbat dinner. And then he sent me back to my hotel (where everyone wondered what had happened to me), bearing a box of matzah and what we decided had to be the only two cans of Chicken of the Sea tuna for thousands of miles.

I leapt at the chance to meet the refuseniks, not even considering that perhaps our tourist minders might not take kindly to my stepping away from the group yet again. When we got back to Moscow a few days later, I went to a pay phone, feeling as if I was in a spy movie. I asked for the individual whose name Rabbi Teitz had given me and explained how I had gotten his name and number. He told me to be at the Revolyutsii metro station Friday afternoon at 3 p.m.. People would meet me. He also told me to take multiple trains in different directions to get there, in case I was being followed.

The paranoia in the Soviet Union was hard to describe. One moment sums it up. On a bus tour around Moscow, our Intourist guide pointed out KGB Headquarters, a squat, ugly building in what was then known as Dzerzhinsky Square. She told us, with tart Russian humor, that KGB Headquarters was the tallest building in Moscow, “because you can see Siberia from the basement.”

When you’re 20, you don’t think about the KGB or putting yourself in danger. It’s just all excitement. So when 2 p.m. on Friday came, I broke off from my group, headed to a metro station, and took trains in three different directions until I reached Revolyutsii station at 3 p.m.. Two men with beards were waiting for me at the station entrance. They escorted me to an apartment block a few blocks from the station. Once up five flights of stairs and into the apartment building, they introduced me to the crew—six men and one woman who were preparing for that evening’s Shabbat meal.

World War II had destroyed much of the Soviet Union’s housing stock, and even by the late 1970s, complete strangers still had to share apartments intended to be occupied by one small family. The refuseniks occupied half of an apartment that they shared with a Gentile couple. Every time any of us stepped out of the Jewish side, we had to remove our kippot.

They put me to work peeling potatoes, explaining that even the great rabbis of the Talmud would help prepare the food for Shabbat. I had never peeled a potato in my life, but I wasn’t about to tell them. Although maybe they figured it out from my handiwork. (I’m told it hadn’t gotten any better by the time I was helping to prepare the men’s club kiddushin at Bnai Yeshurun in Teaneck.)

They mentioned that they were big fans of U.S. Senator Henry “Scoop” Jackson, who had taken up the refuseniks’ cause. The Soviet Union was facing major grain shortages at the time, so Jackson arranged for refuseniks to leave the U.S.S.R. in exchange for much-needed grain. “Your Senator Jackson trades wheat for Jews,” one said approvingly.

We davened at sunset and had a beautiful Shabbat meal together. I wasn’t the only visitor—there were two British businessmen who, like Rabbi Teitz, shared a deep concern for their Soviet Jewish brethren. The meal was beautiful—a traditional Shabbat dinner with cabbage soup, chicken and tzimmes, and of course, my potatoes. I could have been anywhere in the world eating the same meal.

After the Birkat Hamazon, one of our hosts escorted the two British men and me down the five flights of stairs and to the street, as is Jewish tradition. As we walked back to the hotel district, one of the British men pointed out that our host had fashioned a tie clip out of a paper clip, so he would not be guilty of carrying in the public domain on the Sabbath.

“They try so hard to do it right, it breaks your heart,” he said.

The businessmen explained that these Jews were practically destitute, since they had no income, and lived with the threat of imprisonment hanging over their heads because they were technically “hooligans”—people without work.

He explained that their needs included shortwave radios with built-in cassette players, so that they could record and pass around Hebrew lessons from Kol Yisrael, the Voice of Israel. They needed anything Jewish—siddurim, tefillin, you name it. I told them there were a lot of Jewish kids in my group and many of them had brought things to give to Soviet Jews. “Come back next week with your friends,” they told me. Anything you bring will be most welcome.

I spread the word throughout my group, and we piled up huge bags of Jewish ritual items, blue jeans (which sold for a fortune on the black market), and other clothing we had brought from the United States. We went to the berioshkas, the foreign currency stores where typical Russians were not allowed to shop, and bought shortwave radios and other consumer goods. We kept everything stacked up in my hotel room, and my roommate and I never left the room unattended during the days we were amassing the gifts for our new friends.

Finally, that Friday afternoon, we grabbed the stuff and took trains in three different directions until we reached Revolyutsii station. We carried the goods up five flights of stairs to our grateful hosts, and we had a Shabbat meal together. Unforgettable.

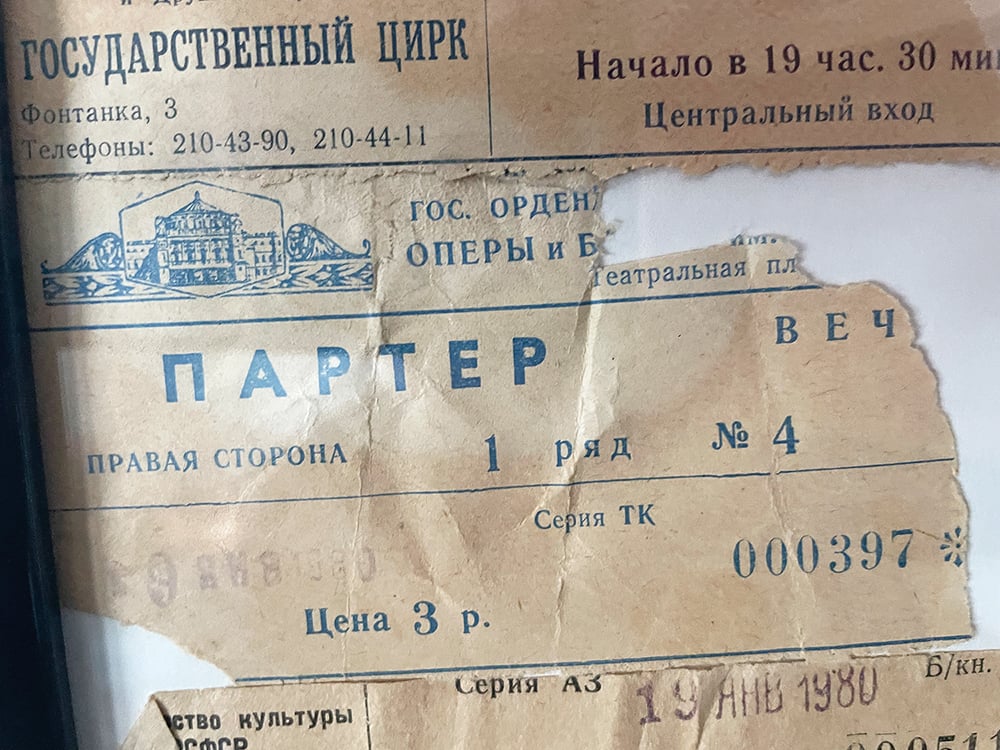

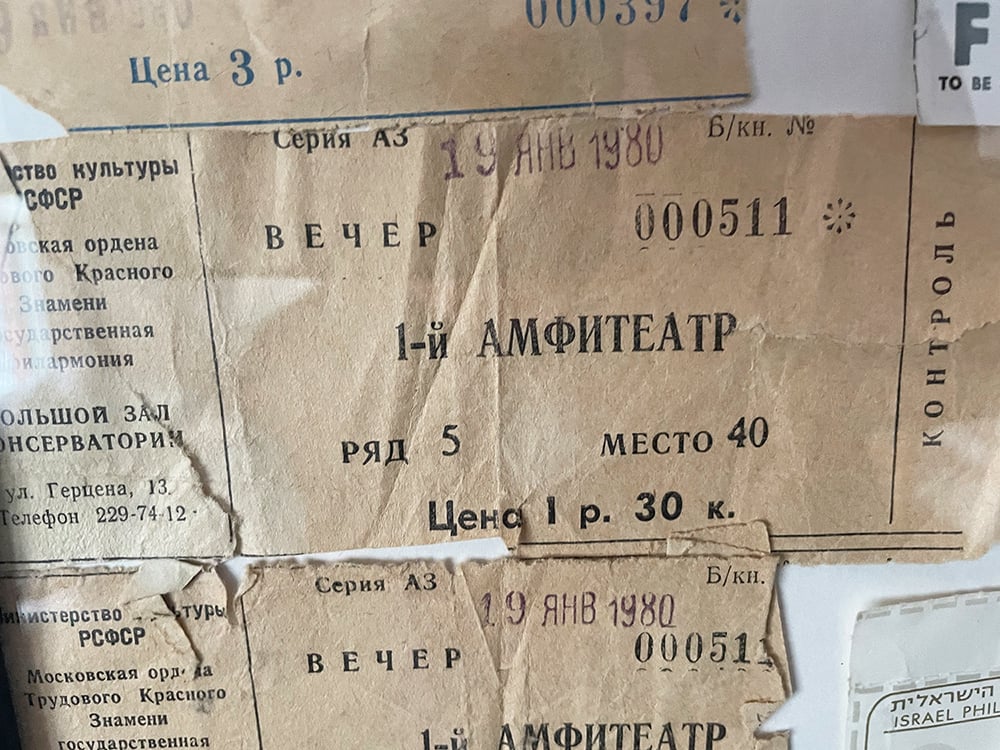

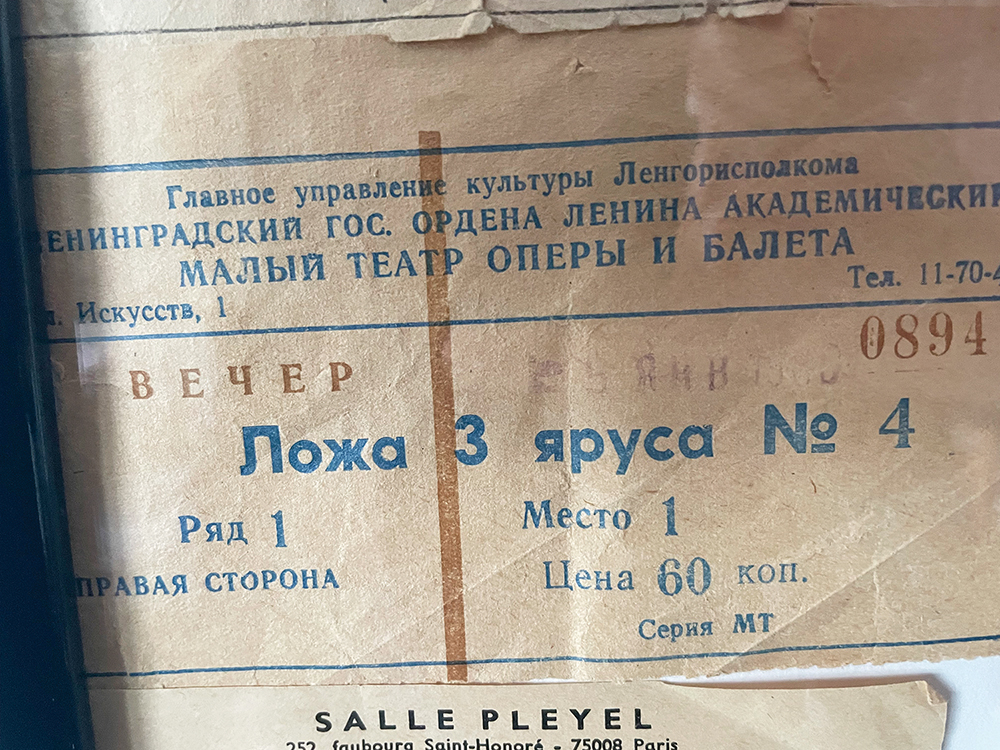

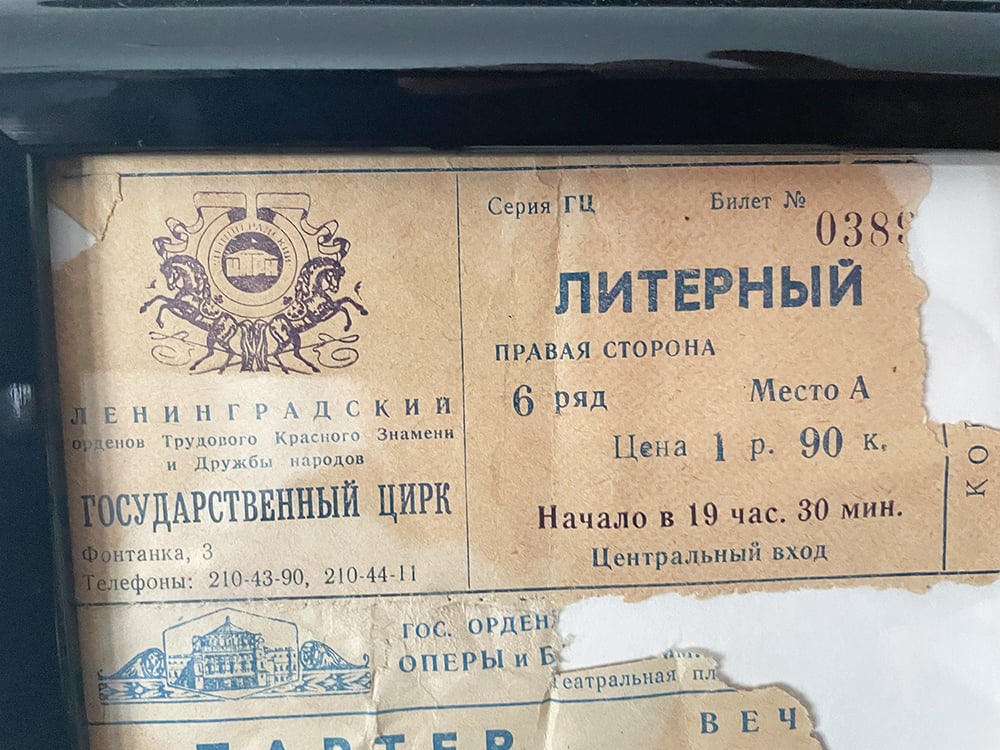

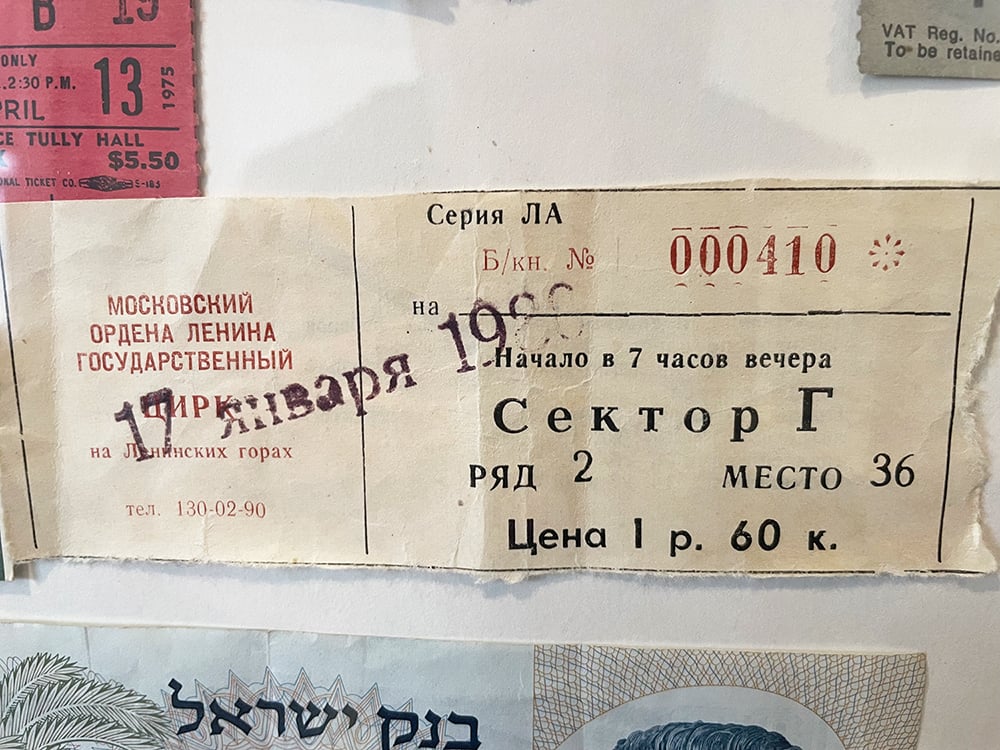

One other memory from the trip: In Leningrad, now St. Petersburg, I left the group yet again. How I got away with it, I have no idea. This time, I went to the theater where the Kirov Opera and Ballet performed. I wanted to scalp a ticket for myself. I had already done so in Moscow, and I got to see the Bolshoi Ballet. Here in St. Petersburg, I found the lighting director of the theater willing to sell a ticket for a couple of rubles.

He looked at me and asked if I was Jewish. I nodded.

“So am I,” he said. “Meet me after the show. I want to show you something.”

That something turned out to be his father’s sculpture studio on the banks of the Neva River, a few blocks from the theater. His father was a master sculptor and had done an exquisite sculpture in wood of an elderly couple emerging from the Holocaust. He explained that the Soviet Union wanted to put the pieces in a museum, where they belonged, because of their high quality, but his father refused, because they would not pay him for the sculptures.

“My father is not a boy,” he told me in halting English, leaning on one of the sculptures of the elderly couple. In other words, he would love the honor of having his work in a museum, but not if they were going to insult him by offering no money.

We arrived home from the trip the Sunday of the Super Bowl. Maybe I had a few seforim smuggled in my suitcase as a favor to Rabbi Teitz. Back in the States, tens of thousands of fans on television were screaming and waving their “terrible towels” to support the Pittsburgh Steelers. I didn’t realize that I had already inhaled the paranoia that exists in the Soviet Union until that moment. My first thought, seeing them waving those towels was “Are they crazy? They should calm down! Somebody is going to see them!”

The effects of that trip were profound. I couldn’t stop thinking about how hard the Jews of the Soviet Union had to work just to express their religious beliefs, the odds they were up against, the misery, poverty and despair. I decided that if the refuseniks I met could turn a paperclip into a tie clip so as not to violate Shabbat, why couldn’t I be fully observant here in the comfortable, religiously tolerant United States?

And here we are, 45 years after that trip. The Soviet Union has fallen. The refuseniks were finally able to leave. Today, Moscow and Kiev are at war. And I’m still observant.

It is said that we live life forward and understand it only looking back. What a gift from God that I was able to go on that trip, meet Rabbi Teitz, encounter the refuseniks and be inspired by them. And by telling this story today, I hope that their faith inspires you, too.

Teaneck resident and New York Times bestselling author Michael Levin runs www.JewishLeadersBooks.com.