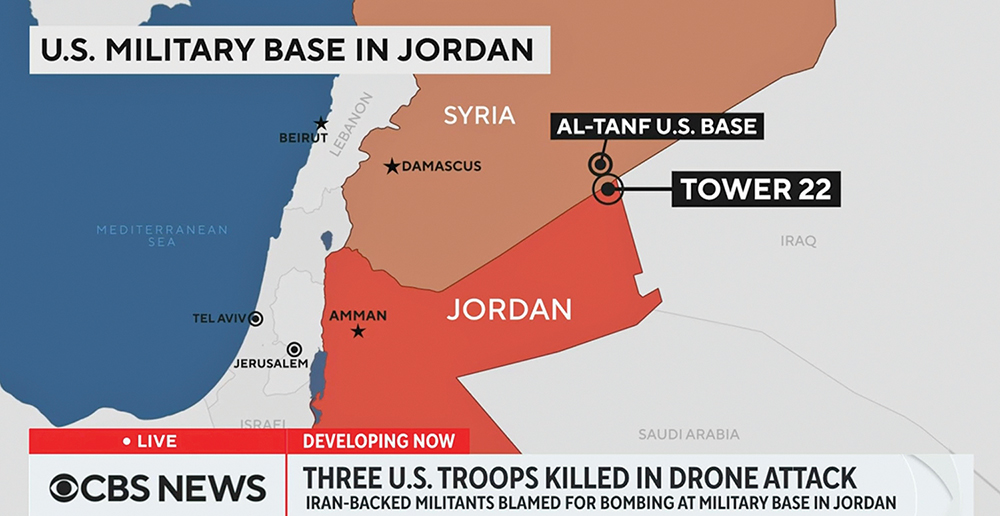

“When will you ever learn?” asked the refrain in Pete Seeger’s classic anti-war song, “Where Have All the Flowers Gone.” “When will they ever learn?”The question is especially pressing today as the White House decides how and where to respond to the drone attack by an Iranian-backed militia, on a U.S. military base in Syria that killed three and wounded 35 soldiers. Yet the question is hardly new.

“When will they ever learn?” could have been asked repeatedly of American policymakers who, for many years now, have refused to understand that ignoring aggression and broadcasting fear in the Middle East is the surest way to encourage aggression and realize that fear. They’ve failed to grasp that there are societies which, unlike the West, place religious beliefs far above financial incentives and are unwilling to trade the former for the latter. They have never learned that stopping local wars before their allies have won results in larger wars that can engulf the region if not the world.

For more than 15 years, the United States has consistently overlooked Iran’s belligerency. Whether for missile boat attacks on Navy vessels in the Persian Gulf or rocket strikes against Army bases in Syria and Iraq or for its involvement in the narcotics trade and terror plots in America itself, the U.S. has never held Iran accountable. In flagrant violation of its international obligations and while consistently lying about its nuclear program, Iran has built underground enrichment facilities and produced enough fissile material for multiple nuclear bombs.

America’s response was to acknowledge Iran’s right to enrich and to incentivize the ayatollahs monetarily to delay their enrichment program for several years. That, in essence, was the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan for Action, the Iran nuclear agreement which American leaders hoped would enable them to disengage from the Middle East and pivot further eastward to China.

Led by elites, most of whom had long ceased to regard religion as a serious political force, the United States believed that the Islamic Republic could easily be bought off. Not so. The aftermath of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) saw Iran’s sphere of influence spread across Iraq and Syria and through Lebanon to the Mediterranean coast, as well as southward, to Yemen. Its terrorist proxies threatened American allies in the Middle East and steadily surrounded Israel on virtually every border.

America’s response was to again express fear of escalating conflicts and to stop its allies from winning decisively over terror. Accordingly, in 2021, the Biden Administration cut off its support for Saudi Arabia’s military campaign against the Iranian-backed Houthis in Yemen. Washington later removed the Houthis from its list of terrorist organizations. Starting in 2006 with Israel’s war with Hezbollah in Lebanon, and then repeatedly—in 2009, 2012, 2014, 2021—in clashes between Israel and Hamas in Gaza, the United States worked to impose a ceasefire. War, to paraphrase John Lennon, was never given a chance.

The result was a greatly emboldened Iran and terrorist proxies confident in America’s determination to step in and prevent their defeat. At the same time, U.S. forces largely withdrew from the Middle East, leaving a diplomatic and strategic vacuum readily filled by other powers. Before long, China had signed a 25-year oil-for-technology-and-arms deal with Iran and negotiated a Saudi-Iranian rapprochement. Russia began purchasing many thousands of Iranian-built drones and missiles.

By 2023, the Middle East had become a powder keg with multiple Iranian flashpoints. Needed only was a spark. It came in the form of a belated American attempt to broker a peace deal between Israel and Saudi Arabia. That treaty, if achieved, would have threatened Iran with a Saudi-Israeli military and economic front and, more intolerably from Tehran’s perspective, a Saudi nuclear program. The easiest way to preempt the agreement was to start a minor war.

The location for doing so, logically, was Gaza. Not unlike the United States, Israel had proceeded on the belief that Hamas could be bribed, all the while declaring its fear of invading the Strip and losing 500 soldiers. Like Iran, Hamas took advantage of the situation by massively expanding its power, mounting a force of 30,000 gunmen and excavating nearly 400 miles of underground tunnels. It garnered the immense amount of intelligence necessary to break through Israel’s border defenses and penetrate military bases and civilian communities. Though definitive evidence linking Iran to that attack has yet to surface, enough circumstantial proof exists—meetings between senior Iranian and Hamas leaders, Iran’s training of Hamas terrorists—to make such a connection all but irrefutable.

In its initial response to the October 7 atrocities, the Biden Administration was unequivocal in its support of Israel’s right to defend itself and categorical in its condemnation of Hamas terror. But, from the outset, Biden warned Israel of its need to conform to international law and limit as much as possible the damage to Gaza’s civilian population. In time, as the number of Palestinian civilian deaths climbed, the White House became increasingly critical. The fact that Hamas makes “life extremely difficult for Israel” by shooting from behind civilians, stated National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan, “does not lessen Israel’s responsibility … to protect the lives of innocent people.” Vice President Kamala Harris, insisting that “Israel must do more to protect innocent civilians,” suggested that it had failed to abide by international humanitarian law. “Far too many Palestinians have been killed,” declared Secretary Blinken—bizarrely, for it raises the question how many Palestinians casualties would have been enough. Israel, President Biden himself warned, was losing global support due to its “indiscriminate bombing” in Gaza.

Israel expressed sorrow for the rising Palestinians losses while also rejecting the administration’s charges. Hamas, Jerusalem countered, routinely inflated the number of Palestinian civilian dead, and included among them the thousands of terrorists killed by Israel. Deducting the civilian casualties caused by the 30% of Hamas rockets that fell short within Gaza, and the ratio of civilian-to-combatant fatalities was less than two-to-one. In America’s wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, as well as NATO’s 1999 intervention in Bosnia, the ratio was four-to-one.

The IDF, Israel stressed, was fighting against an enemy that not only used civilians as human shields but also their towns and cities, under which stretched hundreds of miles of attack tunnels. There was no way to fight such an enemy but to urge civilians to evacuate combat areas. Even then, Hamas continued to battle from within the refugee concentrations. America, Israelis believed, should show greater understanding of these realities and support the IDF’s efforts to grapple with them.

Yet still the criticism continued. In addition to its genuine concern for the Palestinians, the White House was sensitive to mounting condemnations of Israel in the U.N. and throughout the world. Entering a presidential election year, the administration also needed to placate a progressive base increasingly dissatisfied with its backing of Israel and to cater to public opinion in key states such as Michigan.

Above all, the United States wanted to avoid getting dragged into a broader Middle Eastern war. Significant pressure was levied on Israel not to open a second front against Hezbollah in the north, even as the terrorists shot numerous rockets into Upper Galilee and displaced its entire civilian population. A war with Hezbollah, capable of launching as many as 6,000 rocket strikes per day—far more than Iron Dome could intercept—would almost certainly force the U.S. to come to Israel’s defense.

But Washington’s criticism of Israel signaled to Hamas that all it needed to do was to hunker down its tunnels, create a situation in which more Palestinians civilians would be killed, and the United States would eventually call for a ceasefire. America’s fear of foreign entanglements, especially with Iran, told Tehran that its Hezbollah proxy could continue to shell northern Israel without concern for American intervention.

Iran subsequently hiked up rocket and drone assaults on U.S. bases in the region and supported the Houthis’ efforts to close the strategically and commercially vital Bab al-Mandeb straits, challenging America’s longstanding role as guardian of the freedom of the sea and driving up global shipping prices.

Via the Houthis, the Iranians were revisiting the OPEC precedent of the 1973 Yom Kippur War, pressuring the United States and the West economically to abandon Israel. The U.S., in concert with several other nations, responded with multiple missile strikes against Houthi emplacements. No action, however, was taken against Iran, nor would the Biden Administration formally blame the ayatollahs for their role in setting much of the Middle East ablaze.

“The Zionist regime and its supporters have been defeated,” declared Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi in a speech marking the 100th day of the Gaza War. “The resistance of the Iranian nation,” he proclaimed, “has paid off.”

Raisi may have a point. Engaged militarily on two fronts—a third one, on the West Bank, brews—and with tens of thousands of its citizens displaced, charged with committing genocide for defending itself against an attempted genocide, and increasingly isolated internationally, Israel can indeed seem to be losing.

But so, too, can the United States. By sending mixed messages to the Middle East, denouncing Israel’s military tactics while resupplying it with ammunition and opposing calls for a ceasefire, and by showing fear, rather than backbone, in the face of Iranian aggression, the U.S. is only inviting defeat.

“Unless the U.S. prepared for an all-out war, what does attacking Iran get us?” asked an unnamed high-level defense official supuesto by Reuters. The answer is simple: By not attacking Iran, the U.S. is not diminishing but, on the contrary, greatly increasing the chances for war.

An alternative course would be for America to declare its unqualified support for Israel in its complex and costly battle with Hamas, and to show Iran in indisputable terms that it will be held accountable for each and every attack by its proxies and that no target—military or nuclear—is immune.

Rather than strike at an Iranian proxy, for example, the U.S. could destroy the Iranian factory that produced the drone that killed the three American soldiers. That same factory no doubt produced the drones that are murdering Ukrainians. Bombing it would deter, not provoke, Iran, and restore credibility to America’s military threats.

The more credible those threats, ironically, the more the United States will be far less likely to have to resort to them in the future. Only by standing foursquare behind its allies and instilling fear in our common enemies will America be able to answer the question “When will they ever learn?” with the single word, “Now.” Only then, perhaps, will people no longer wonder where all the flowers have gone.

Michael Oren, formerly Israel’s ambassador to the United States, Knesset member, and deputy minister for diplomacy in the Israeli prime minister’s office, is the author of the Substack publication Clarity. This article first appeared in Clarity.